by Mysia Perry

Mysia Perry is a rising sophomore from Richmond, VA with an intended major in Leadership Studies and minor in Sociology and Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies. She is a part of the WILL* program, Peer Advisors and Mentors, Planned Parenthood Generation Action, and she is both an Oldham and Oliver Hill Scholar. This is her first summer working on the Race & Racism Project on Team Oral History, and she is very excited to begin working for more equitable environment here at the University of Richmond.

CNN reported that, as of 2016, there were about 1,500 monuments to the Confederacy in public spaces throughout the United States. As I explored the internet searching for this number, I found myself wondering why we are so obsessed with the “losers.” America, and the South specifically, has developed this obsession with redefining how we see the Civil War because of all the shame that we hold as a result of its causes. From this fixation stems sayings such as “heritage not hate” and protests to removal of these monuments to the Confederacy. How are we in a country that has spent so much time condemning the controversial pasts of other countries, yet we have no fear in highlighting the scars of ourselves under false pretenses?

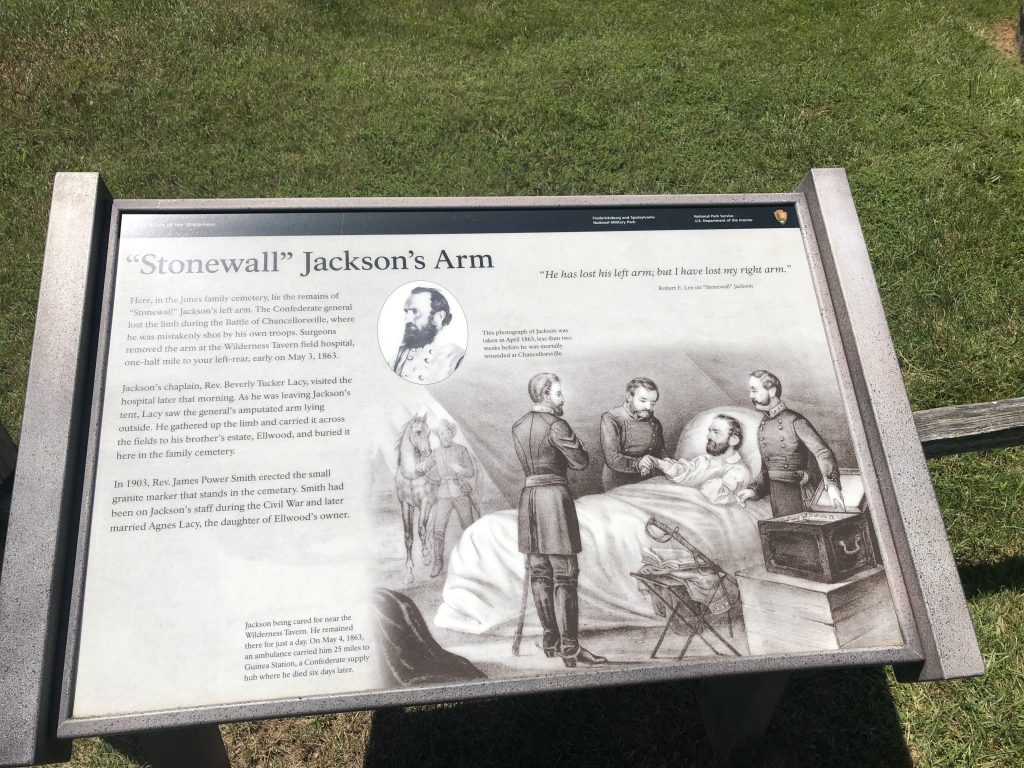

In the center of all of this, is the former home of the capital of the Confederacy, Virginia. Virginia is reported to have the most symbols, 223 to be exact, to the Confederate States of America. One of the 223 Virginian symbols (and probably the most peculiar) is a monument to the arm of Confederate General “Stonewall” Jackson. On the land of Ellwood Manor, in a family cemetery, lays a single rock to memorialize the arm of Lieutenant General Thomas Jonathan “Stonewall” Jackson. As Dr. Nicole Maurantonio, Ayele d’Almeida, and I approached the manor, we were greeted by representatives of the Friends of Wilderness Battlefield, where they told the story of why “Stonewall” Jackson’s arm laid on the property, separate from the rest of his body in Lexington. We learned that after being caught in the crossfire of his own troops at the Battle of Chancellorsville, Jackson was cursed to have his arm amputated. As a result, his arm was buried on the site in the Jones’ family plot after it was found lying on the ground by a chaplain. Because it was given a “christian burial,” Jackson’s wife allowed it to remain there.

In the center of all of this, is the former home of the capital of the Confederacy, Virginia. Virginia is reported to have the most symbols, 223 to be exact, to the Confederate States of America. One of the 223 Virginian symbols (and probably the most peculiar) is a monument to the arm of Confederate General “Stonewall” Jackson. On the land of Ellwood Manor, in a family cemetery, lays a single rock to memorialize the arm of Lieutenant General Thomas Jonathan “Stonewall” Jackson. As Dr. Nicole Maurantonio, Ayele d’Almeida, and I approached the manor, we were greeted by representatives of the Friends of Wilderness Battlefield, where they told the story of why “Stonewall” Jackson’s arm laid on the property, separate from the rest of his body in Lexington. We learned that after being caught in the crossfire of his own troops at the Battle of Chancellorsville, Jackson was cursed to have his arm amputated. As a result, his arm was buried on the site in the Jones’ family plot after it was found lying on the ground by a chaplain. Because it was given a “christian burial,” Jackson’s wife allowed it to remain there.

This story led us to question what truth it held. Why would Mary Anna Jackson allow her husband’s arm to be kept separate from his body? What proof do we have that the arm is there at all? How do we know if the marker was even placed correctly, being that it was erected forty years later? As these questions ran through our heads, the three of us began to head not far from the manor, through a small path and up the hill to a small area where it is said that Jackson’s arm is buried. There is little signage regarding the history of “Stonewall” Jackson or why it took until 40 years after his death for a marker to be erected for the arm. This exhibit left so many questions unanswered: What exactly was so great about “Stonewall” Jackson that his arm became worth memorializing? What happened in the forty years it took to erect the memorial? Who else was buried in this Jones’ family cemetery and where were their markers?

This monument did nothing to signify the hurt and damage that this man had caused and, in some ways, worshipped him. The monument did no work to highlight the purpose of the war he fought in. This monument chose to ignore the amount of lives that were lost in the battle, in addition to “Stonewall” Jackson’s. It highlights a quote from Robert E. Lee that celebrates “Stonewall” Jackson, but does no work to acknowledge the enslaved people that Jackson was fighting to keep in chains. The accompanying signage of Ellwood Manor also does little to acknowledge these lives, with only one sign that highlights how the enslaved people did “chores” and had fun in the late night hours. This monument did no work to expose how ideals of white supremacy have repressed the stories of marginalized groups, like enslaved people. Instead, this monument spotlighted how their stories remain nonexistent in our historical narratives.