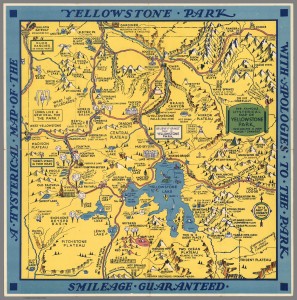

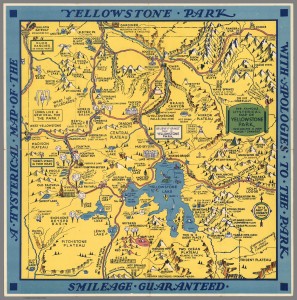

At first glance, Jolly Lindgren’s 1936 map, “A Hysterical Map of the Yellowstone Park with Apologies to the Park”, immediately pulls you in with its intensely mustard-yellow color and its “Smileage Guaranteed” promise. Its initial intrigue is a result of its strangeness and deviation from the typical historical and roadmaps of the period, but upon further analysis of its historical context, this map gains a deeper meaning as a tool to mitigate the cultural anxiety of Americans during the Great Depression.

Firstly, a description of Lindgren’s map: The entire park is colored yellow, possibly indicative of the park’s name, with the roads clearly marked in red. All throughout the map are drawings of mountains and their respective elevations. These elevations are the only numbers on the map. The most obvious missing parts of the map are the legend and scale, which is ironically replaced by a musical note scale. The locations of interest are accompanied by small, pictorial representations of their names. For instance, Hot Springs is literally a picture of springs that are sizzling. These interest points are included for the benefit of a tourist; the map shows hotels, large waterfalls, peaks, Yellowstone’s famous geysers, and so on.

This map was created during the Great Depression and it represented one possible way that Yellowstone was imagined, which created a sense of escape for its dispirited readers during this time of great suffering for America and the world, The Great Depression is most often remembered as the decade of bread-lines, Hoovervilles, and the plunging of the American morale. From this psychological pit emerged the humor of the 1930s, which served to combat the “creeping paralysis of will and spirit that had sapped the American people”(American Literary). Lindgren implements this 1930’s humor in the creation of his map of Yellowstone Park in order to lift the burdens of his audience, if only for a few moments. Among the characteristics of 1930s humor is the use of silliness. The original intention behind creating Yellowstone Park was to protect its natural “curiosities” and “wonders” (National Parks for). Lindgren uses these “curiosities” to project silliness on to the map with small pictorial representations, from the “Hot Springs” on the bottom to the “Gr-r” of “Roaring Mtn.” in the upper half to the left. In addition, the gaudy yellow that covers the entire map conveys a sense of happiness. Because the yellow is unnaturally mustard-colored, it contrasts sharply with the real natural world and works to transport the reader into a alternate world, where their suffering is alleviated. This color was chosen for all of Lindgren’s Hysterical Maps, as it draws attention to the map while helping its reader escape the anxiety of the Great Depression.

Lindgren’s map also uses another characteristic of the humor of the 1930s, its ironic critique of previous eras, in his Yellowstone map. He incorporates this by using what Wood would call “silences”. The audience expects a traditional historical map, but that expectation is immediately rejected upon reading the title, which makes a point of calling the map “hysterical”. The title also points out that the map includes “ a few minor ? changes”, while the changes are actually huge contrasts to the typical map. Usually, maps try to project a scientific reality through preciseness, but this map makes no such effort; instead, it uses irony to mock this type of mapping. The lack of a legend and the use of an unconventional scale and uncertain compass rose all display this map’s immense amount of irony, amusing the audience while critiquing traditional “scientific” maps. As Wood discusses, legends can be dispensable and when they are used, they only explain a portion of the symbols on a map. By leaving out the legend, Lindgren is challenging the idea that they are needed at all to understand maps. He also notes that a scale is unimportant to his own map by replacing the numerical scale with a musical one, a gently ironic stab at precise, “true” maps. The amusement continues with the compass rose, which claims that “This part is correct, so ‘elp me,” implying that the rest of the map may be wrong. This directly contrasts with the priority of scientific maps, which focus on being precise and promote “objectivity”. By leaving out numerical measurements and the typical tools of a map, Lindgren is arguing that this objectivity does not really exist in mapping. The end result is a map that is focused on being extremely amusing and symbolic through its cartoonish puns, while playfully subverting conventions of mapping at the same time.

This map also functions as an encouragement to readers to leave their worries behind for a bit and enjoy nature in Yellowstone, if not by physically traveling then by imagining a trip there. During the 1930s, Yellowstone started building shelters for cars in the park and paving its roads in order to accommodate tourist travel. This marked Yellowstone as a destination to visit, a place to spend leisure time, and something to get Americans’ minds off of their troubles. Visitation exploded with the automobile and as a result of the park’s efforts. Lindgren’s map emphasizes this tourism-driven aspect of Yellowstone by clearly distinguishing its roads with a bold red color and displaying the points of interest all along these roads. This purposely shows the ease with which a tourist could visit the “wonders” of the park, effectively shouting “Come and visit!” Even if the reader could not physically go to Yellowstone, due to restrictions of money or daily life, this map creates an optimistic geographic imagination, which Schulten writes about, that relieves the burden of the Great Depression, if only for a moment. It creates a space in the geographic imagination of America where there is the possibility of pure enjoyment. The yellow covering the entire park applies this idea of pleasure to the idea of Yellowstone and helps socially construct Yellowstone to be associated with happiness. All the reader had to do was imagine a trip to Yellowstone and they could escape the burden of the Great Depression, if only for a short time.

The humorous nature of the pictorial representations, dramatically giddy yellow color, and tourist-focused nature of the Lindgren’s map give it a personality of its very own. With its musical scale, Lindgren’s map is definitely not a calculated, scientific map that pretends to be purely objective. Instead, it becomes a “living and breathing” active document that creates a whole new, happy reality for its burdened audience. Its joking tone tells the story of a fun-filled, yet leisurely, trip to Yellowstone Park to escape the struggle of everyday life that remained the reality during the Great Depression.

Bibliography

Gates, Robert Allan. American Literary Humor During the Great Depression. Westport, CT: Greenwood, 1999. Print.

Lindgren, Jolly. A Hysterical Map of the Yellowstone Park with Apologies to the Park. Lindgren Brothers, 1936. Accessed October 15, 2014. http://www.davidrumsey.com/luna/servlet/detail/RUMSEY~8~1~260351~5522946:A-Hysterical-Map-of-the-Yellowstone#

Machlis, Gary E., and Donald R. Field. National Parks and Rural Development: Practice and Policy in the United States. Washington, D.C.: Island, 2000. Print.

McClelland, Linda Flint. Building the National Parks: Historic Landscape Design and Construction. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, 1998. Print.

National Parks for a New Generation: Visions, Realities, Prospects: A Report from the Conservation Foundation. Washington, D.C.: Conservation Foundation, 1985. Print.

Schulten, Susan. The Geographical Imagination in America: 1880-1950. Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press, 2001.

Wood, Denis. The Power of Maps. New York: Guilford, 1992. Print.