© 2013 Rick Hutchins

© 2013 Rick Hutchins

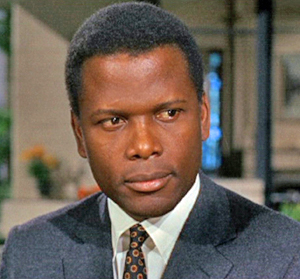

The word revolution suggests noise. People will do a lot to draw attention to their cause; yelling and shouting is usually the least of it. But some revolutions happen quietly, peacefully, inevitably. All Sidney Poitier had to do to change the world was to be Sidney Poitier.

His humble beginnings did not in any way suggest greatness. A premature baby born to a poor farming family from the Bahamas, he survived infancy against the odds. His early life in the islands, in Miami and in New York was an anonymous one of farming and odd jobs, primarily washing dishes. He did not learn to read until his late teens. After a stint in the army, he simply went back to washing dishes. While he was able to gain a spot in the American Negro Theater, his early appearances were not applauded.

Then things changed. One successful role on Broadway led to another, which led to a notable role in the film No Way Out, which led to more Hollywood successes. Suddenly this quiet, perseverant man was a star — the first Black actor to be nominated for a competitive Academy Award, then the first Black actor win the Academy Award for Best Actor.

But he was more than that. In the tempestuous 1960s, in the midst of the Civil Rights Era, a time of race riots and student protests and a counter-cultural overturning of tradition, a time of clashes between generations and ideologies and bewildered bystanders,  a time in which the pent-up anger of centuries came to a head, Sidney Poitier found himself to be a role model. Without any ambition to do so, he touched the lives of millions.

a time in which the pent-up anger of centuries came to a head, Sidney Poitier found himself to be a role model. Without any ambition to do so, he touched the lives of millions.

You could hear a pin drop.

This is not to say there was no controversy; nothing and no one is immune to that. There were accusations of tokenism, of appeasement. With his serene manner, his gentle voice — even after all these years still informed by a gentle island lilt — and his general thoughtfulness, this gentleman was deemed by many to be inadequate to the revolution. As the only major Black actor of his time, he was encouraged to take stronger, grittier, more controversial roles — in the parlance of the age, Blacker roles.

Poitier was conflicted. He did not disagree, since, as does any artist, he thrived on challenge. But, in his thoughtful way, he determined that living up to his own expectations as a role model was more important. He did indeed tackle the great racial issues of his time– a man of his character could do no less– but he did it his own way.

In the classic film Guess Who’s Coming To Dinner?, a movie whose theme of the marriage between a Black man and a White woman (miscegenation!)  was still unspeakably scandalous to much of the nation, his character quietly said to his father, “You think of yourself as a colored man. I think of myself as a man.”

was still unspeakably scandalous to much of the nation, his character quietly said to his father, “You think of yourself as a colored man. I think of myself as a man.”

And that was it. While others accused and attacked, he led by example. While others incited passion, he incited peace. While others were fighting battles, he won the war by teaching us that the entire conflict was based on a lie.

Of course it’s not over, even after all these decades; the troubled times are not behind us. There is still racism and chauvinism, still confusion and chaos, still antisocial throwbacks and self-serving crusaders. Even so, standing serenely above them all is a giant named Sidney Poitier– actor, director, author, diplomat– a role model for those with sincerity in their hearts, a leader for those who will listen.

Sidney Poitier, you see, is not too quiet — the world is simply too loud.

– – – – – – – – – – –

Rick Hutchins was born in Boston, MA, and is a regular contributor to this blog. In his quest to live up to the heroic ideal of helping people, he has worked in the health care field for the past twenty-five years, in various capacities. He is also the author of Large In Time, a collection of poetry, The RH Factor, a collection of short stories, and is the creator of Trunkards. Links to galleries of his art, photography and animation can be found on http://www.RJDiogenes.com.

Two of Hutchins’ previous essays on heroes appear in our new book Heroic Leadership: An Influence Taxonomy of 100 Exceptional Individuals.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –