The famed comparative mythologist Joseph Campbell once said, “We must be willing to get rid of the life we’ve planned, so as to have the life that is waiting for us.”

Campbell was profoundly wise. He knew that the hero’s journey was the grand blueprint for each human being’s path in life. Our journeys are wild and unpredictable to us despite the pattern of the journey being plainly evident in every novel that we read and in every movie that we see. My own personal journey fits the Campbellian path and led me to the study of heroism.

Studying heroes was not on my to-do list as a young assistant professor. Years ago I was interested not in great people, but in the types of situations that give rise to cooperative behavior in groups. I published a number of studies that examined the conditions under which people placed their group’s welfare ahead of their own individual welfare (e.g., Allison & Messick, 1985, 1990; Samuelson & Allison, 1994). Not surprisingly, these conditions were hard to find, as people tend to show self-serving biases in their distributions of resources and in their self-assessments of their morals and abilities. I was struck by the ways in which subtle variations in the environment could lead people down the path of either selfishness or selflessness (Allison, McQueen, & Schaerfl, 1992). It wasn’t quite heroism research but my research did focus on the factors that tend to make people behave badly – or well – in group settings.

Then in 1991, I found myself teaching a “great books” humanities course to first-year students at the University of Richmond. The course was multi-disciplinary and multi-cultural in its emphasis, and it required students to read such books as Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, Plato’s Symposium, Darwin’s Origin of Species, the Analycts of  Confucius, Naguib Mahfouz’s Fountain and Tomb, Orhan Pamuk’s The White Castle, and many other great texts from around the globe. What most caught my attention were the two epic stories on the course syllabus: The Epic of Sundiata told by the Malinke people of Africa, and the epic novel Monkey (also known as Journey to the West) written by Wu Cheng’en during China’s Ming dynasty.

Confucius, Naguib Mahfouz’s Fountain and Tomb, Orhan Pamuk’s The White Castle, and many other great texts from around the globe. What most caught my attention were the two epic stories on the course syllabus: The Epic of Sundiata told by the Malinke people of Africa, and the epic novel Monkey (also known as Journey to the West) written by Wu Cheng’en during China’s Ming dynasty.

These two epic adventures were composed at different points of time in human history, and in different parts of the world, and yet they bore a striking resemblance to the two great western epic stories I had read in high school and in college, namely, the Iliad and the Odyssey. The Epic of Sundiata tells the story of the hero Sundiata Keita, the founder of the Mali Empire. Born an ugly hunchback, Sundiata was prophesized to become a great ruler of the Mali people. The existing king felt threatened by this prophecy and thus banished Sundiata from the kingdom, but years later Sundiata returned to defeat the king and establish the great empire. In Monkey, a brave young pilgrim named Tripitaka must travel to strange faraway places to retrieve sacred information needed to enlighten the entire Chinese people. Tremendous courage, wisdom, and virtue are needed by Tripitaka to accomplish this objective.

People’s fascination with old dead legendary figures caught my attention. Nearly every psychological theory I had encountered was centered on people’s fascination with living people, not dead people, and so I sensed an opportunity to study how human beings perceive and evaluate the dead. This led my colleagues and I to write articles on the death positivity bias – the tendency of people to evaluate the dead more favorably than the living (Allison, Eylon, Beggan, & Bachelder, 2009). It also led to our discovery of the frozen in time effect – people’s tendency to resist changing their evaluations of the dead even when new information surfaces that challenges that evaluation (Eylon & Allison, 2005).

Then, plain old good luck came my way. In 2005, my dear friend and colleague, George Goethals, who had toiled for decades at Siberia-like Williams College in Massachusetts, decided to move south and join me on the faculty at the University of Richmond. Goethals came with an  expertise in leadership and an impeccable scholarly record. He and I had collaborated in Santa Barbara back in the mid-1980s while I was a graduate student at the University of California. At that time, Goethals was visiting Santa Barbara while on leave from Williams, and he, David Messick, and I embarked on a collaborative project that, on the surface, would seem to have no connection to heroism at all. We set our sights on understanding self-serving biases in social judgments.

expertise in leadership and an impeccable scholarly record. He and I had collaborated in Santa Barbara back in the mid-1980s while I was a graduate student at the University of California. At that time, Goethals was visiting Santa Barbara while on leave from Williams, and he, David Messick, and I embarked on a collaborative project that, on the surface, would seem to have no connection to heroism at all. We set our sights on understanding self-serving biases in social judgments.

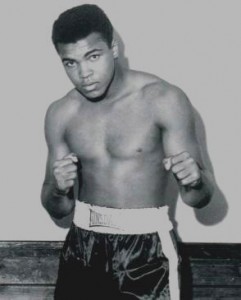

Yet somehow, there was indeed an indirect connection to heroism, although we weren’t consciously aware of it at the time. Looking back at our 1980s collaborative work in Santa Barbara, I should have realized that some day Goethals and I would surely write about heroes. The first paper we published together, along with David Messick, was inspired by one of our heroes, the boxer Muhammad Ali. We were always fascinated by Ali’s influence and leadership outside the ring, particularly his role in making race relations change in the United States. Ali was always his own man. He insisted on being called Muhammad Ali rather than what he referred to as his slave name, Cassius Clay. At first the media refused to go along. But as we know from his long boxing career, Ali never quit. Eventually sports writers and broadcasters recognized that he was right to insist that they call him what he wanted to be called. He led the way for many, many more African Americans to use names that reflected their pride in their racial identity. There was no doubt that he was the first, and that he led the way.

As George Goethals and I tried to identify the qualities that made Ali an effective leader to a largely hostile white establishment, we focused on his wit and his obvious linguistic intelligence. We remembered that when Ali was once asked whether he had deliberately faked a low score on the US Army mental test, so that he could avoid the draft, he mischievously quipped, “I never said I was the smartest, just the greatest” (McNamara, 2009). That self-characterization led us to research some of the limits on people’s self-serving biases. The result was our Social Cognition paper, “On being better but not smarter than other people: The Muhammad Ali effect” (Allison, Messick & Goethals, 1989).

Army mental test, so that he could avoid the draft, he mischievously quipped, “I never said I was the smartest, just the greatest” (McNamara, 2009). That self-characterization led us to research some of the limits on people’s self-serving biases. The result was our Social Cognition paper, “On being better but not smarter than other people: The Muhammad Ali effect” (Allison, Messick & Goethals, 1989).

At that point neither of us had turned to studying heroism or leadership or the connections between them. But we were inching closer in that direction. I joined the faculty at Richmond in 1987 and continued to conduct work focusing on pro-social behavior in groups, examining the conditions under which people place their group’s well-being ahead of their own individual interests. Goethals, meanwhile, returned to Williams and was publishing some great work on group goals, social judgment processes, and eventually leadership.

When Goethals was coaxed to join the faculty at Richmond in 2004, he and I renewed our collaboration, this time focusing on the underdog effect – the tendency of people to root for disadvantaged entities in competition. This research was borne out of our earlier interest in such diverse heroes such as Muhammad Ali, Sundiata, and Odysseus, all of whom somehow overcame the most terrible adversity to achieve greatness. Goethals and I embarked on a research program exploring people’s love for underdogs (Kim et al., 2008), and this research evolved slowly into work examining triumphant underdogs who became exemplary leaders and heroes. Our interest in underdogs, Goethals’ exceptional scholarship on U.S. Presidents, and my own research on people’s reverence for the dead (Allison et al., 2009), all eventually led to the books and articles on heroes that Goethals and I have written today (Allison & Goethals, 2008, 2011, 2013, in press; Goethals & Allison, 2012).

Our first book on heroes, Heroes: What They Do & Why We Need Them (Allison & Goethals, 2011) addressed the psychology of constructing heroes in our minds as well as the path that great heroes take when they perform their heroic work. Although scholarship on leadership, particularly Howard Gardner’s (1997) Leading Minds, was always important in the way we thought about heroes, our general exploration of the psychology of heroism diverted us from focusing on the connections between leadership and heroism. Those connections were explored more fully in our review article in Advances in Experimental Social Psychology (Goethals & Allison, 2012), where Goethals and I proposed a conceptual framework for understanding heroism in terms of the influence that heroes exert. Heroes, we argued, vary in their depth of influence, their breadth of influence, their duration of influence, and the timing of their influence.

But there was clearly much more to consider. This became increasingly clear in 2010 when we started to blog about heroes. Within four years we have written more than 150 hero analyses, attracting hundreds of thousands of visitors to the blog. Exactly 100 of our hero profiles were included in our book on Heroic Leadership (Allison & Goethals, 2013). Profiling so many great individuals made it increasingly clear that all of our heroes were also leaders. They might not fit traditional leader schemas, or people’s implicit theories of leadership, but they were clearly leaders in the sense that Gardner defined it in 1997. Either directly or indirectly, through face-to-face contact or through their accomplishments, products and performances, heroes influence and lead significant numbers of other people.

Let me share two observations about the history of our ongoing research on heroism. These reflections speak more to the path we have taken in my work than they do to any destination we have reached. My first observation is that we have benefited from researching the concept of heroism from multiple paradigmatic angles and methodological perspectives. For over thirty years  we’ve looked at selfless behavior using case studies, interviews, surveys, experimentation, dispositional analysis, and contextual approaches. Philosopher William James once wrote that science is best served when scientists not only remain open to fresh perspectives, but actively seek them out. James believed that a single perspective offers but a mere, limited slice of the world (James, 1909/1977). Adopting multiple scientific perspectives expands what one can observe and thus can learn about a phenomenon (James, 1899/1983b). I have found this idea to be certainly true in my study of heroism.

we’ve looked at selfless behavior using case studies, interviews, surveys, experimentation, dispositional analysis, and contextual approaches. Philosopher William James once wrote that science is best served when scientists not only remain open to fresh perspectives, but actively seek them out. James believed that a single perspective offers but a mere, limited slice of the world (James, 1909/1977). Adopting multiple scientific perspectives expands what one can observe and thus can learn about a phenomenon (James, 1899/1983b). I have found this idea to be certainly true in my study of heroism.

My second observation relates to the Joseph Campbell quote that began this essay. We may think that we can plan how our careers will unfold, but in reality outside forces are always at work that have a far more powerful effect on our professional lives than anything we could ever imagine. What exactly are these “outside forces”? They are the influential people, resources, circumstances, luck, and zeitgeist which are forever lurking and shifting around us. For me, these factors included David Messick’s willingness to serve as my advisor in graduate school, George Goethals’ decision to choose Santa Barbara as the location for his leave in 1985, my choice to work at a small liberal arts school like Richmond which offered that “great books” course, Richmond’s school of leadership offering a position to Goethals in 2004, and many, many more happy chance events.

The serendipitous events that shape our lives are inescapable. During my career, I have been swept and swayed by these influences and have tried not to fight them but to embrace them. These ever-present and ever-changing forces underscore the truism that nothing we can plan in life is ever as special as the unintended route we ultimately take. Dan Gilbert, the eminent social psychologist at Harvard University, was once asked, “What’s the key to success?” His immediate reply: “Get lucky. Accidentally find yourself at the right place at the right time.” The idea here is that while we’d like to think we are the architects of our own destiny, we are more the product of forces beyond our control than we would like to think. Gilbert later went on to explain this idea more fully in his best-selling book entitled, appropriately enough, Stumbling on Happiness (Gilbert, 2007).

“Serendipity,” wrote scientist Pek van Andel, “is the art of discovering an unsought finding.” Many unsought events had to come together for George Goethals and me to embark on our exploration of heroes. The beautiful orchestration of unpursued circumstances led to the books and articles on heroism that we published (Allison & Goethals, 2008, 2011, 2013, 2015; Goethals & Allison, 2012, 2015; Goethals, Allison, Kramer, & Messick, 2015). The wondrous thing about serendipity is that it has our best interests in mind, as long as we trust it. We need only remain open to receiving, and capitalizing on, the unexpected gifts and opportunities that sly happenstance throws our way.

References

Allison, S. T., Eylon, D., Beggan, J.K., & Bachelder, J. (2009). The demise of leadership: Positivity and negativity in evaluations of dead leaders. The Leadership Quarterly, 20, 115-129.

Allison, S. T., & Goethals, G. R. (2008). Deifying the dead and downtrodden: Sympathetic figures as inspirational leaders. In C.L. Hoyt, G. R. Goethals, & D. R. Forsyth (Eds.), Leadership at the crossroads: Psychology and leadership. Westport, CT: Praeger.

Allison, S. T., & Goethals, G. R. (2011). Heroes: What They Do and Why We Need Them. New York: Oxford University Press.

Allison, S. T., & Goethals, G. R. (2013). Heroic Leadership: An Influence Taxonomy of 100 Exceptional Individuals. New York: Routledge.

Allison, S. T., & Goethals, G. R. (2015). “Now he belongs to the ages”: The heroic leadership dynamic and deep narratives of greatness. In Goethals, G. R., Allison, S. T., Kramer, R., & Messick, D. (Eds.), Conceptions of leadership: Enduring ideas and emerging insights. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Allison, S. T., & Goethals, G. R. (2015). Hero worship: The elevation of the human spirit. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour.

Allison, S. T., & Messick, D. M. (1985). Effects of experience on performance in a replenishable resource trap. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 49, 943-948.

Allison, S. T., & Messick, D. M. (1990). Social decision heuristics and the use of shared resources. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 3, 195-204.

Allison, S. T., McQueen, L. R., & Schaerfl, L. M. (1992). Social decision making processes and the equal partitionment of shared resources. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 28, 23-42.

Allison, S. T., Messick, D. M., & Goethals, G. R. (1989). On being better but not smarter than others: The Muhammad Ali effect. Social Cognition, 7, 275-296.

Eylon, D., & Allison, S. T. (2005). The frozen in time effect in evaluations of the dead. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31, 1708-1717.

Gardner, H. (1997). Leading minds — An anatomy of leadership. Harper & Collins, London.

Gilbert, D. (2007). Stumbling on happiness. New York: Vintage.

Goethals, G. R. & Allison, S. T. (2012). Making heroes: The construction of courage, competence and virtue. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 46, 183-235.

Goethals, G. R., & Allison, S. T. (2015). Kings and charisma, Lincoln and leadership: An evolutionary perspective. In Goethals, G. R., Allison, S. T., Kramer, R., & Messick, D. (Eds.), Conceptions of leadership: Enduring ideas and emerging insights. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Goethals, G. R., Allison, S. T., Kramer, R., & Messick, D. (Eds.) (2015). Conceptions of leadership: Enduring ideas and emerging insights. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Goethals, G. R., Messick, D. M., & Allison, S. T. (1991). The uniqueness bias: Studies of constructive social comparison. In J. Suls & B. Wills (Eds.), Social Comparison: Contemporary theory and research (pp. 149-176). New York: Lawrence Erlbaum.

James, W. (1977). A pluralistic universe. In F. H. Burkahradt, F. Bowers, & I. K. Skrupskelis (Eds.), The works of William James. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. (Original work published 1909)

James, W. (1983b). What makes a life significant? In F. H. Burkahradt, F. Bowers, & I. K. Skrupskelis (Eds.), The works of William James: Talks to teachers on psychology and to students on some of life’s ideals (pp. 150–167). Cambridge: Harvard University Press. (Original work published 1899)

Kim, J., Allison, S. T., Eylon, D., Goethals, G., Markus, M., McGuire, H., & Hindle, S. (2008). Rooting for (and then Abandoning) the Underdog. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 38, 2550-2573.

Mackie, D. M., Allison, S. T., Worth, L. T., & Asuncion, A. G. (1992). The impact of outcome biases on counter-stereotypic inferences about groups. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 18, 44-51.

McNamara, M. (2009). Muhammad Ali’s new fight: Literacy. Retrieved from http://www.cbsnews.com/2100-18563_162-2207050.html on June 15, 2012.

Samuelson, C. D., & Allison, S. T. (1994). Cognitive factors affecting the use of social decision heuristics when sharing resources. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 58, 1-27.

By Nelly Spigner

By Nelly Spigner complete liberation from the chains of the past, all the while producing a culture they could be proud of.

complete liberation from the chains of the past, all the while producing a culture they could be proud of. Offering a holistic take on an emerging field,

Offering a holistic take on an emerging field,

By Kathryn Lynch

By Kathryn Lynch According to Si, “I know they are tired of living here. They have had difficulties. They have no one to help them.”

According to Si, “I know they are tired of living here. They have had difficulties. They have no one to help them.” they pushed him away and yelled in his face, content to accept their fate, and did not believe they were worthy of help and compassion.

they pushed him away and yelled in his face, content to accept their fate, and did not believe they were worthy of help and compassion.