© 2013 Rick Hutchins

© 2013 Rick Hutchins

It seems like it should be very simple-– the definition of heroism. And yet, as we’ve seen, any attempts to delineate a definitive set of properties or criteria result in debate, disagreement and dissatisfaction. The more we try to pin down the concept, the more amorphous it seems. This is because heroism is not an intrinsic property, but an emergent one. In the words of the great philosopher Anonymous, “Heroes are made, not born.”

This is not to say that the potential for heroism does not exist in everyone, but acts of heroism are decidedly situational. The woman who saved her platoon in Afghanistan may be useless when her neighbor’s cat is stuck up a tree –- she’s afraid of heights. Or the man who quietly devoted ten years of his life to caring for his sick mother may not be the person you want around if you’re drowning –-  he never learned to swim. The scientist whose vaccine saved countless lives may lack the upper body strength to pull an unconscious adult from a burning building. The great orator whose speeches inspired millions may lack the esoteric knowledge needed to assist somebody having an epileptic seizure.

he never learned to swim. The scientist whose vaccine saved countless lives may lack the upper body strength to pull an unconscious adult from a burning building. The great orator whose speeches inspired millions may lack the esoteric knowledge needed to assist somebody having an epileptic seizure.

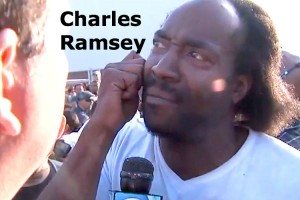

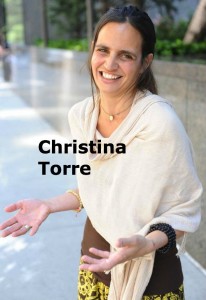

However, on another day, an undistinguished man with a questionable past may be sitting on his front porch, hear a cry for help, and find himself rescuing several kidnapped women from their captor. Or perhaps a woman who was previously known only as a baseball player’s daughter may be walking down the street, minding her own business, and find herself  catching a one-year-old baby who fell from a fire escape. Or perhaps a middle-aged construction worker, waiting for a train with his two kids, will find himself saving the life of a seizure-stricken stranger who fell upon the tracks. Or perhaps a shopper at the supermarket, thinking only of taking home some groceries, may find himself performing CPR on the still body of a child, bringing her back to life.

catching a one-year-old baby who fell from a fire escape. Or perhaps a middle-aged construction worker, waiting for a train with his two kids, will find himself saving the life of a seizure-stricken stranger who fell upon the tracks. Or perhaps a shopper at the supermarket, thinking only of taking home some groceries, may find himself performing CPR on the still body of a child, bringing her back to life.

Ordinary people, ordinary days, ordinary circumstances that suddenly blossom into extraordinary events. What seems inevitable is averted. Like life itself, heroism is a thing of self-organizing complexity, emergent, synergistic-– an antidote to entropy.

It is inevitable that we should seek to understand the existence and nature of heroism. Seeking to understand is one of the essential qualities of humanity and we are rightfully amazed at a universe that can give rise to beings who can conceive of such a sublime, but slippery, idea. Yet we also must realize that concepts in the abstract have no perfect analogs in the physical world.  The zen concept of a chair is perfect to the intellect, but only infinite imperfect variations exist in reality. We can calculate the mathematical properties of a perfect circle, but no such thing exists outside the realm of pure thought. When the abstract is made real, it is unique and unprecedented-– it is emergent-– and, while it may have aspects in common with past examples, attempting to formalize the concept in absolute terms is like trying to psychoanalyze a person not yet born.

The zen concept of a chair is perfect to the intellect, but only infinite imperfect variations exist in reality. We can calculate the mathematical properties of a perfect circle, but no such thing exists outside the realm of pure thought. When the abstract is made real, it is unique and unprecedented-– it is emergent-– and, while it may have aspects in common with past examples, attempting to formalize the concept in absolute terms is like trying to psychoanalyze a person not yet born.

Perhaps, then, the best way to define heroism is to understand that heroism defines itself.

– – – – – – – – – – –

Rick Hutchins was born in Boston, MA, and is a regular contributor to this blog. In his quest to live up to the heroic ideal of helping people, he has worked in the health care field for the past twenty-five years, in various capacities. He is also the author of Large In Time, a collection of poetry, The RH Factor, a collection of short stories, and is the creator of Trunkards. Links to galleries of his art, photography and animation can be found on http://www.RJDiogenes.com.

Two of Hutchins’ previous essays on heroes appear in our book Heroic Leadership: An Influence Taxonomy of 100 Exceptional Individuals.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

Heroism is also a bit of a judgment call. Does the heroic actions of an individual outweigh the human frailties they have?

Thanks for this interesting post. In response, I wrote two separate blog posts, one in disagreement with the concept of not coming up with a definition for heroism (http://kohenari.net/post/56343971607/heroism-cant-define-itself) and one that agrees with the notion of emergence that is briefly outlined here (http://kohenari.net/post/56444140525/heroism-emergent).

In addition, Matt Langdon and I spent some time discussing the situational context of heroism on our most recent podcast: http://kohenari.net/post/56976618546/pod58

superb article and so right about heroism being about people and situations

Thank you all very much for your responses. Mr. Kohen, I appreciate your interest in my thoughts and will check out your blog.

Does performing CPR qualify someone as a hero? What about those who provided first aid immediately after the bombings at the Boston Marathon last year? Are they heroes?

If you asked the individuals involved in these situations, they would deny it. Many have been quoted as saying they were doing only what they hoped others would do if an emergency happened. So why the hero designation? Perhaps because others did not act and rally to help others?

Maybe we should not define those who act in an emergency as heroes, but instead ask why others did not respond. Shouldn’t the base expectation be that all able bodied people are prepared and willing to help in an emergency?