There is a surprisingly profound line towards the end of Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone. It is uttered by Professor Dumbledore, who says “It takes great deal of bravery to stand up to our enemies, but just as much to stand up to our friends”. This idea is particularly true in warfare where actions by enemy troops are vilified, while actions by friends and allies are often excused or ignored. We see this phenomenon play out even today as the United States struggles with whether “enhanced interrogation” techniques are legal and ethical, and with the legitimacy of killing civilians during drone strikes.

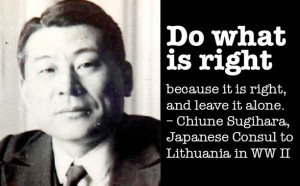

This was a situation facing a man named Chiune Sugihara in the waning years of Imperial Japan when he bore witness to the beginning of one of the most abhorrent acts of evil ever committed. Born in Yaotsu, Japan on January 1, 1900, Chiune Sugihara was raised in a middle-class rural family. His physician father had wished him to follow in his footsteps but Chiune purposely failed the required exams and instead majored in the English language and passed the Foreign Ministry Scholarship exam. He was soon recruited by the Japanese Foreign Ministry and sent to China.

It was in China that hints of his future acts of heroism would come to light. During this time Japan had invaded China and the mistreatment of the locals was commonplace. In protest of the way the Chinese were being treated, Chiune resigned his post as Deputy Foreign Minister in Manchuria.

In 1939 Chiune was then sent to the Japanese Consulate in Lithuania. On September 1st of that year Nazi Germany invaded Poland and the persecution of Jews began almost immediately. By 1940 Jewish refugees from Poland and from within Lithuania itself began to seek ways to flee the country. This required visas and many countries were refusing to issue them. Japan itself had stringent requirements that the refugees did not meet. Chiune inquired to his superiors three times requesting instructions, but in all cases requests to issue the visas were declined.

By 1940 Jewish refugees from Poland and from within Lithuania itself began to seek ways to flee the country. This required visas and many countries were refusing to issue them. Japan itself had stringent requirements that the refugees did not meet. Chiune inquired to his superiors three times requesting instructions, but in all cases requests to issue the visas were declined.

It might have been easier to simply walk away and do nothing but instead, in July of 1940, against orders, Sugihara started issuing visas and even directly negotiated with officials of the Soviet Union to allow the refugees to pass through Russia on their way to Japan. He continued to write visas, reportedly spending 18-20 hours a day until September 4th when the Consulate was closed. During the night prior to the closing, Chiune and his wife Yukiko spent the entire night writing visas, and Chiune was reportedly even preparing them en route to the train station where he threw them out the window of the train to waiting refugees as it left the station. In a final act of desperation he resorted to throwing blank pages with the Consulate seal and his signature, which could be filled out later.

The exact number of Jews saved by Chiune Sugihara is not known but estimates put the number around 6,000. By comparison Oskar Schildler saved around 1,100 to 1,200 lives.  Chiune’s actions seemed to have given him few accolades immediately after the war. The Japanese foreign office asked him to resign due to downsizing — though some have suspected it might have stemmed from his activities in Lithuania. To make a living he began selling light bulbs door-to-door and later he found work in an export company.

Chiune’s actions seemed to have given him few accolades immediately after the war. The Japanese foreign office asked him to resign due to downsizing — though some have suspected it might have stemmed from his activities in Lithuania. To make a living he began selling light bulbs door-to-door and later he found work in an export company.

Finally in 1968 he was located by one of his beneficiaries and later visited Israel. In 1985 he was awarded the Righteous Among the Nations award by the Israeli government. In June of the next year Chiune Sugihara passed away in Kamakura, Japan. Today he has streets in Lithuania named after him, an asteroid (25893 Sugihara), a synagogue in Massachusetts, a memorial at his birthplace and in Lithuania, and a memorial in Little Tokyo in Los Angeles. It seems inaccurate to refer to Chiune Sugihara as an “unsung hero” due to his many honors but many more should hear his story.

– – – – – – – – – – – –

The author, Jesse Schultz, has contributed several other essays on heroism here, including Love Thy Enemy: Opposing Heroes and Night Witches: the Forgotten Aviatrixes. Two of his previous blog posts on Merlin and The Makers of Fire will appear in our new book Heroic Leadership: An Influence Taxonomy of 100 Exceptional Individuals.

Unbelievable. Six thousand lives saved by one man. To save one life is an amazing and wonderful thing, but six thousand– that’s a rare level of heroism. It’s nice that he was recognized and honored before he died, but it’s a shame that someone who contributed so much to Humanity went unrewarded in his lifetime. He is certainly a shining example of what one person can accomplish by, as you say, just not walking away.

I also can’t help but smile at the weird historical irony of saving Jews from Nazis by smuggling them into Japan. Life is truly stranger than fiction. 😀

It is definitely a heroic step to save so many lives, despite the dangers of disobeying instruction. Thank you for talking about this man – of whom I previously knew nothing – a hero indeed.

Amazing… I was born in 1936 and was very aware of the threat of Japanese planes, and black outs, and air raid wardens with helmets, knocking on doors, calling out “lights out”, or , “close the curtains or shades”. That was in Long Beach, Ca. I saw propaganda movies about The Japanese pilots, smiling, smiling, always smiling, as they shot down our pilots. This renews my faith. Some were so brave, to risk revenge for doing the right thing. May this brave man RIP