By Scott T. Allison and George R. Goethals

By Scott T. Allison and George R. Goethals

In an earlier blog post, we outlined the various stages of the hero’s journey in mythology and literature as described in 1949 by Joseph Campbell. In the prototypical hero story, he or she is called to an adventure, sometimes reluctantly, and is swept into another world fraught with danger. In this strange world the hero undergoes many tests and trials, gets help from unlikely sources, and is often distracted by a romantic interest. In the end, the hero overcomes great obstacles, returns home as a person transformed, and is the master of both worlds. It is a timeless story structure that has assumed countless forms in hero tales across the globe.

But what of the villain? Nearly every hero story has one, yet far less attention has been devoted to understanding the life story of the prototypical villain in myth and legend. Do heroes and villains travel along a similar life path? Or do villains experience a journey that is the inverse of that of the hero?

The answer to the first question appears to be, yes, there are parallels between the lives of heroes and villains. Christopher Vogler, a noted Hollywood development expert and screenwriter, once wrote that villains are the heroes of their own journeys. Vogler believed that whether a character is working toward achieving great good or great evil, the general pathway is similar.  Both heroes and villains experience a significant trigger event that propels them on their journeys. Heroes and villains encounter obstacles, receive help from sidekicks, and experience successes and setbacks during their quests.

Both heroes and villains experience a significant trigger event that propels them on their journeys. Heroes and villains encounter obstacles, receive help from sidekicks, and experience successes and setbacks during their quests.

While we do not disagree with this general parallel structure, we’ve observed that many stories portray villains as following the hero’s life stages in reverse. We first came across this idea from writing expert Greg Smith, who found an interesting writer’s web discussion board post by an individual going by the username of RemusShepherd. The idea is compelling: Whereas heroes complete their journey having attained mastery of their worlds, the story often begins with villains possessing the mastery. That is, hero stories often start with the villains firmly in power, or at least believing themselves to be superior to others and ready to direct their dark powers toward harming others.

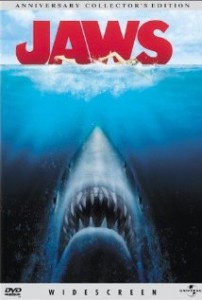

Examples abound. Consider the Wicked Witch in The Wizard of Oz, the shark in Jaws, Nurse Ratched in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, Buffalo Bill in Silence of the Lambs, and Annie Wilkes in Misery. In these examples, the story begins with the villain securely in power, the master of his or her world. The heroes of these stories, in contrast, are weak and naive at the outset. Only after being thrust into the villains’ worlds do these heroes gather the assistance, resources, and wisdom necessary to defeat the villains.

The villain’s story is thus one of declining power while the hero’s story is one of rising power. But before this pattern is made clear, there must be one or more epic clashes between the hero and villain, with the hero embodying society’s greatest virtues and the villain embodying selfishness and evil. In defeat, the villain’s mastery is handed over to the hero. The villain’s deficiencies of character have been exposed; the hero’s deficiencies have been corrected.  The two journeys, one the inverse of the other, are completed.

The two journeys, one the inverse of the other, are completed.

And so here we see that Vogler and RemusShepherd may both be correct – heroes and villains may follow similar life journeys but these journeys are often staggered in time within the same story structure. This temporal staggering may create the illusion that heroes and villains follow inverse paths. Consider the opening act of a typical hero story; the naïve and deficient hero is just beginning his journey while the villain is at the height of his powers. Movie franchises may later release prequels that reveal how the villain acquired such power in the first place. In these prequels we witness a villain backstory that parallels the first movie’s portrayal of the hero’s journey.

A fine line often separates heroes from villains, a line that is clearly delineated in their opposing moral ambitions. But the line can also be blurred when we recognize that all transforming journeys — whether for good or for evil — must share many common storytelling elements.

References

Allison, S. T., & Goethals, G. R. (2008). Deifying the Dead and Downtrodden: Sympathetic Figures as Inspirational Leaders. In C.L. Hoyt, G. R. Goethals, & D. R. Forsyth (Eds.), Leadership at the crossroads: Psychology and leadership. Westport, CT: Praeger.

Goethals, G. R. & Allison, S. T. (2012). Making heroes: The construction of courage, competence and virtue. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 46, 183-235.

– – – – – – – – – – – –

Very interesting thoughts. It certainly deserves more attention and I’m not sure I have a definitive opinion at the moment. You already addressed one of my initial impressions when you noted that the two journeys are usually staggered– the beginning of the story being told coincides with the beginning of the hero’s journey, but the villain’s story is already in progress– probably because the villain’s journey is required to precipitate the hero’s journey. But even so, the villain’s journey must be the inverse of the hero’s to some degree, as his journey must end in failure, while the hero’s must end in triumph.

I must think about this some more. Being a writer, I want to be able to quantify all this and then use the knowledge to invent a new story structure. 😀

In the fuzzy middle-ground of all this is the anti-hero. Someone who is for all practical purposes a villain, like a gangster from an old film, who rises to power (similar to the usual heroes tale) but ultimately falls from grace (as RJ points out, failing as a villain).

If the villain were to succeed and the world in which he and the hero live changes to suit the villain, wouldn’t the villain then become the hero? We only identify the villain in terms of our own laws and definition of good, but if the villain-turned-hero changed the laws he could be considered good then, no? Would he be a good villain, or bad hero?

Through people being misguided, uninformed, or having different perceptions, it has since created the awareness and perception of greyer areas in between heroism and villainy.

In an idealistic world, people would have a clear understanding of who the good guys are and who the bad guys are – only then again, in an idealistic world there wouldn’t be any bad guys…

Still, this was an interesting post. And the villain’s journey often does mirror the hero’s. The existence of evil or lack of presence of heroism is what calls for the need for a hero to fill any theoretical gap.

Without heroes and without villains, and without people like vigilantes who give off mixed perceptions and vibes to the general consensus, everything would just be dull (not necessarily a bad thing – then again, not a good thing, neither) and neutral.

-Tothian