Hundreds of protesters and activists took over the Capitol grounds in Richmond, Virginia, in resistance against Dominion Energy’s plan to dump treated coal ash wastewater into the James River in April 2016.

With its nearly 7.5 billion customers in 18 states, Dominion Energy provides heat, air conditioning and power for homes and businesses throughout our nation. But this doesn’t come without a cost.

For more than 100 years, as America’s economy was growing, people depended on coal to provide them with economical, reliable energy. Coal ash ponds and landfills—where the coal ash that results from producing electricity at these coal power stations is stored—have been used for decades.

The ponds, which leak into the groundwater flowing to the James River, were set to close in April 2015, in accordance with EPA regulations and Virginia requirements for coal ash storage sites. Before this, Dominion had 11 coal ash ponds at four of its facilities and six coal ash landfills at five.

Headquartered here in Richmond, Virginia, Dominion depends on several power stations, the largest of which is only about 20 minutes outside of the downtown area, in Chester, Virginia. Taking up approximately 1,000 acres, this coal-powered station is capable of generating enough power to provide roughly two million households with electricity. I got the chance to visit and tour this station on a rainy April afternoon.

Walking through the station’s hallways, I spoke with technicians Marybeth Barkley and Andrew Perkins, who explained Dominion’s day-to-day functions and showed where the control room, generators and turbines were located within the plant. Obviously proud of their work, the technicians gave detailed descriptions and were open to my questions about the plant.

Two Dominion Energy technicians, Marybeth Barkley and Andrew Perkins, lead a group tour of Dominion’s Chesterfield power station. (Photo by Jasmine Fernandez)

I asked Barkley, a senior chemistry technician at Dominion’s Chesterfield power station, about Dominion’s wastewater disposal process. As this plant’s cooling medium, the James receives the wastewater that remains after Dominion has produced its energy and fueled the homes of its customers.

She explained that the wastewater must pass through condensers, which are treated with bleach. But because of potential harm, “we deactivate the bleach, because any type of biological kill agents can’t go into the rivers,” Barkley said.

The condensers are kept from accumulating green slime by the bleach, she explained. By adding a chemical called sodium bisulfite, Dominion deactivates the killing agent, making the water safe to go back into the river.

But as safe as the wastewater is said to be, the initial step—transporting the ash from Dominion plants to the ponds—is harmful on its own.

I spoke with Kwaku Aduse-Poku, a biodiversity conservation expert and visiting lecturer of biology at the University of Richmond. Passionate about the health and protection of the James, Aduse-Poku’s voice registered concern as he talked about Dominion’s wastewater and what happens once the coal ash leaves Dominion.

“[The waste water] passes through a wetland, and if its not well-covered, then you can have some of the residue flying over,” he said. “If any of it lands in a wetland, that’s not good, because this is highly pollutant stuff.”

Dominion claims that it makes sure it covers these wetlands well.

The effects of coal ash, when it comes into contact with water, are detrimental. The toxic heavy metals contained in the ash can leach or dissolve, which contaminates nearby grounds and surface waters.

In 2018, the energy giant started the process of shutting down six of its 11 ash ponds—four at Possum Point power station in Northern Virginia’s Prince William County and two at Bremo power station, in New Canton, Virginia. Three of the four coal ash ponds at the Possum Point Power Station were reported to have leaked contaminated waste water into nearby Quantico Creek, by the Sierra Club Virginia Chapter, which pledges to protect environmental landmarks such as the James. By the end of this year, the ponds are expected to be closed for good.

As for the five remaining ash ponds at four of Virginia’s power stations, Dominion announced four actions it would take to shut these down in November 2018. These actions included gathering results from a recycling study, an agreement with the Commonwealth of Virginia to monitor the coal ash, examining groundwater results and having a regulatory filing for costs associated with handling the coal ash.

The ponds would be effectively closed by removing the water, leaving the toxic ash in place, and distributing tarps and sod on top of the drained ponds. This coal ash cleanup is not as easy as it may sound, though—the move would cost Dominion billions of dollars, which would be passed on to consumers.

“The whole idea is to dispose of them properly so that the contact with the groundwater becomes minimal,” Aduse-Poku said.

As of now, none of Dominion’s coal ash ponds in Virginia are in use. But five of them still remain.

Aduse-Poku believes that the complete removal of these coal ash ponds will improve the health of the James. Minimizing the contact between coal ash and groundwater will significantly improve the quality of the watershed, including the James.

Dominion will constantly monitor the level of heavy metals within the water, Aduse-Poku said, echoing what Marybeth Barkley had told me back at the Chesterfield power station. As government regulations and policies become more environmentally stringent, she expects Dominion will continue to deal with the challenge of heavy metals, such as arsenic, selenium and mercury.

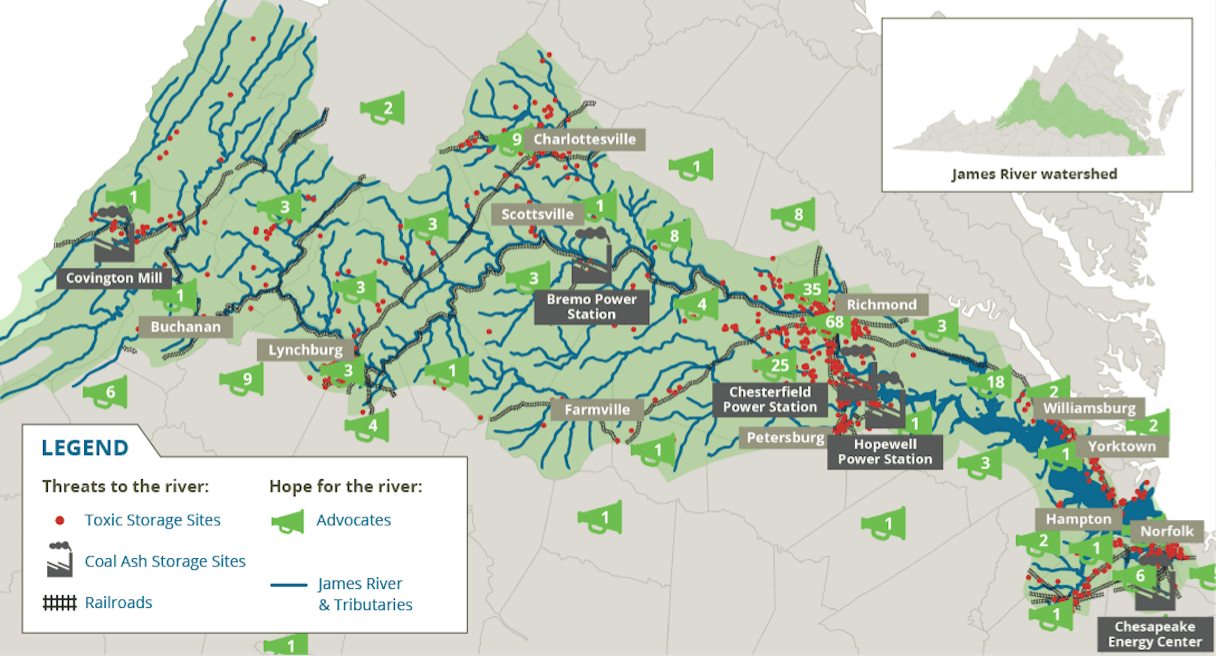

The map below displays the location of Dominion’s power stations with coal ash storage sites. Also mapped are other toxic storage sites, railroads and groups advocating for the river’s health.