Climbers from the VCU Outdoor Adventure Program at the base of Manchester Climbing Wall (Photo by Frances Gichner)

It’s a warm Wednesday in April, late afternoon, and roughly two dozen people stand on a soggy patch of land at the base of a 60-foot-high stack of granite and cement. The James River, in flood stage, surges past, just a few feet away. To get to the base of this wall, one must either repel from the top or tightrope walk, as I did, on wooden boards above the soaked riverbank. The challenge of getting here doesn’t seem to deter anyone. The true challenge is getting up the wall.

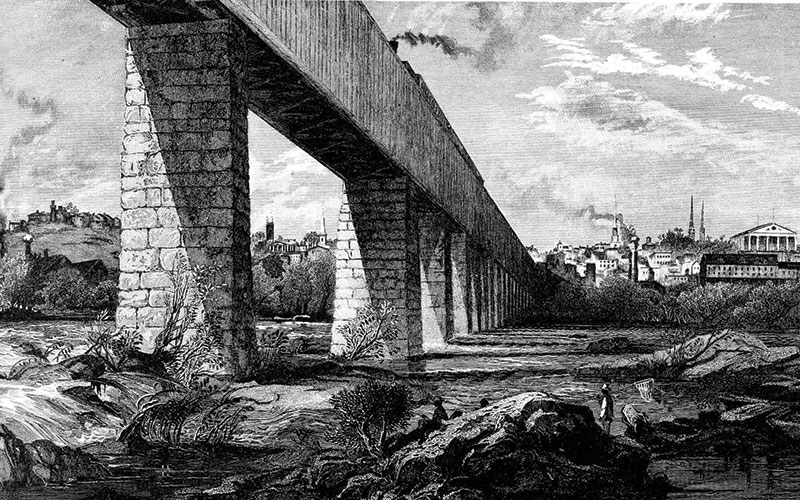

Located on the southern bank of the James River, the Manchester Climbing Wall is Richmond’s equivalent to Yosemite’s El Capitan. Yet this Wall, with its 43 mapped routes, is not the tall natural rock surface one would expect. It’s a pillar of granite that once supported a railroad, built decades before the Civil War.

The original bridge structure, commissioned for the Richmond & Petersburg Railroad in 1836, was a crucial part of the 22-mile Richmond-to-Petersburg track. Designed by Moncure Robinson, a famous Richmond engineer, the bridge spanned half a mile across a particularly treacherous section of the James river near downtown Richmond. Its stone pillars, hand-crafted by Italian stone masons, supported a wooden lattice structure where the tracks laid. The bridge quickly became a commercial success, moving various goods in and out of Richmond. Later, the bridge played a vital role in the Civil War: As part of “Lee’s Lifeline,” it functioned as one of Richmond’s main supply lines from 1860 to 1865. Shortly before Richmond fell, Confederate troops burned the bridge in April, 1865, in an effort to protect the city from General Grant and the Union army, who were advancing on Richmond from Petersburg.

While the original bridge stood for less than 30 years, its stone pillars continue to remain firmly in place, across from Minoru Yamasaki’s Federal Reserve building. Today, the stone towers function as an adult jungle gym.

“Manchester Climbing Wall is such a unique climbing opportunity,” Glenn Rose, a student at the University of Richmond, said. In the climbing world’s debate over natural vs. man-made structures, count him as agnostic. “Anything you can climb and you enjoy is up for grabs!” he says. “With permission of course.”

Rose, originally from Maine, founded an outdoor club on campus to fill the void within the university community.

“A lot of rock climbing is just hanging out at the walls” said Matt Heyrich, a member of the Outdoor Club who picked up climbing in his freshman year. And this, he says, is a “really cool place to learn [the sport].” With its views of downtown Richmond, these granite pillars on the riverbank are a challenge any climber would relish. Plus, “it’s nice to hang out on the river after climbing,” Heyrich said.

These stone pillars have existed as a part of the city’s cultural landscape for nearly two centuries now. And with the Richmond Riverfront Plan underway, it looks like these “majestic ruins,” as they are referred to in the report, will hold their ground for the foreseeable future.

Video by Gabi Williams.