Volunteers with the Virginia Save Our Streams project collect information on stream health throughout Richmond (Photos by Haley Neuenfeldt)

It’s 6:30 a.m., and the sun is peeking out. There is a golden tone on the rain puddles coming through the newly green trees. It is not warm without the full sun on your face, but it is the perfect weather for a morning run. But, no one is there. The trail remains empty with huge holes and puddles crowding the path. I cannot even see the stream.

Flash forward seven months to April 2019, and the area is almost unrecognizable. Instead of holes and puddles, there are bulldozers and excavators. The northern bank is being graded following over a year of prep work including goats to remove invasive species and archeologists to analyze the land and remains.

This is the Gambles Mill Corridor and Little Westham Creek, located off Westhampton Way at the University of Richmond, which is in the midst of restoring this previously neglected stream. It’s part of an overarching project of local and state non-governmental organizations to restore the James River Watershed, along with others in Virginia.

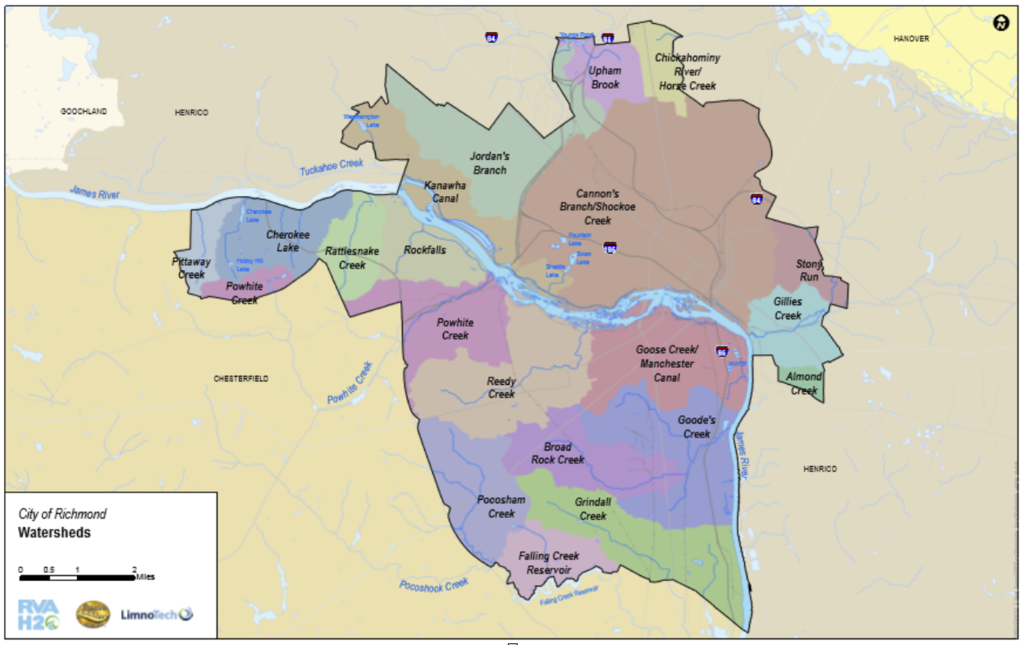

In Richmond, there are 20 sub-watersheds of the James River Watershed. Little Westham Creek is a part of the Kanawha Canal watershed.

Other projects in Richmond include those in Bellemeade, a neighborhood on the south side of Richmond, and part of the Goode’s Creek watershed.

The Bellemeade projected originated from the city’s mission to meet cleanup goals for local waterways that feed into the James River. Similar to the University of Richmond, Bellemeade identified this as an opportunity to not only improve water quality and increase greening, but also to connect people with access to trails and outdoor spaces.

Specifically, an important aspect of the Bellemeade project was educating the community. Watersheds play an integral role in the river’s health, and in urban areas, the disconnect between the two can be even more profound. As an attempt to target this project, Skeo Solutions started a “Walkable watershed” project. With a focus on “equity, community health, water quality, and smart growth,” the project focuses on how a healthy watershed can bring beauty to a community while providing new opportunities for recreation.

Bellemeade’s watershed restoration was completed in 2013. Walking there in April 2019, it looks as if the project was successful. The banks are clean and the bridges– between paneled houses set on black pavement, spotted with potholes and an urban oasis– are still intact. Even more, there are volunteers cleaning up litter and testing the stream quality.

Donna Reese, her husband, and their friend Jim McCord have lived in Richmond for over 30 years. Now retired, they “have a new job” volunteering for the Virginia Save Our Streams program of the Izaak Walton League of America. It’s important work, they say, and well worth their time.

“This is not a healthy stream,” says McCord. “All we are seeing is midges and worms, but at this time of year a healthy stream should have dragonfly and mayfly larva.”

It’s hard to see signs of damage, says Reese, “because this part does look so beautiful. A bunch of native flowers will start to come up soon and it will be even more beautiful. But if you look at what is feeding into the stream—the trash on the street and the sewer—there’s a lot going into the stream and people don’t realize it.”

As they continue to sort for bugs, McCord talks about why he’s here.

“I do this for my grandchildren,” he says. “It doesn’t seem like much, but it’s really important. The health of one stream may not change the health of the river, but the health of a million streams will. I want my grandchildren to have a place to live one day, so I do what I can.”

The River City is named for the city’s main artery, the James River. But throughout the city, there are veins that feed into the main source. Whether people understand the connection between their neighborhood stream and the James River is a good question.

Todd Lookingbill, professor of Biology and Geography at the University of Richmond, references a study conducted by a colleague.

“There was a study on people’s perceptions of the city of Richmond and whether or not they value the James, and most people do,” he said. “Then they were asked whether where they live is connected to the James, and most people said no. They found that it was the people who answered yes to both questions that were the most likely to invest their time and resources into helping protect the river and keep it clean.”

Rob Andrejewski, director of Sustainability at the University of Richmond, noted that the university’s Gambles Mill Corridor and Little Westham Creek project “will definitely physically connect students more to the James River, because the corridor will essentially take them right to the Huguenot Bridge.” Lookingbill added that Ralph White, former director of the James River Park System, suggested building signage and promoting a ‘Spider Trail.’

“Making students aware of the ecological impacts and seeing Little Westham Creek as part of the James River will take a lot of educating,” Andrejewski continued. “There will definitely be benefits to the river, (such as leaking less phosphorus into the James and stabilizing the banks to create a natural floodplain), but teaching students to see the creek as a part of the James River system and making them understand those ecological benefits will be more difficult.”

UR Director of Sustainability Rob Andrejewski answers questions from students in a Landscape Ecology course regarding the Gambles Mill Corridor and Little Westham Creek restoration project.

“There was also a faculty commission that advised the project on ways to integrate the corridor into their classroom and use other aspects of the trail as well. That is definitely a primary goal of the project.”

Watersheds are integral to the health of the James River. Everything in the watershed will eventually end up in the James River. In urban areas such as Richmond, watershed management is often an afterthought, but new methods of restoration can help to promote education about hydrological systems and watershed pollution. With thoughtfulness and intentionality, improving the health of the watersheds might be just what Richmond needs to improve the water quality of the James River.