AS I WALKED ALONG East Clay Street in downtown Richmond, past the VCU Hospital and its sprawling medical center, it would be easy to dismiss the gray, unassuming building, number 1201, for any other historic mansion in the city. But that would be a mistake.

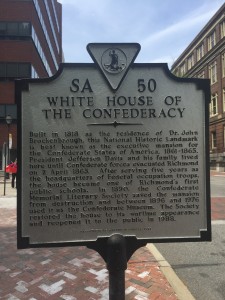

For this is the Confederate White House (right), the former residence of Confederate President Jefferson Davis and his family. Today, the historic home has been restored to its Civil War appearance and is open to tours as a historic site under the umbrella of the American Civil War Museum.

As I followed my guide, Allison Campbell, through the ornate rooms of the house, I learned intimate details about Davis, his wife Varina and their family. Most of Campbell’s stories didn’t dwell on the horrific events of the war, but seemed to highlight Mrs. Davis’ ambivalence towards the war effort, the overall Davis family dynamic, and humanizing Jefferson Davis instead of focusing on his official duties.

One of my favorite stops on the tour was room was dedicated to telling the story of the day President Abraham Lincoln visited the home following the official surrender of Richmond to Union troops, giving context to how historically important the home is.

Each story she told gave me a new perspective and shattered my misconceptions about how people experienced the Civil War in Richmond, whether it was Davis, his wife, his children, or even the slaves and servants that made up the house’s staff.

Like walking through the Confederate White House, walking the streets of Richmond reveals hidden specks of Civil War history on almost every corner. Whether it be the Slave Trail plaques along the streets of Shockoe Bottom, or the historic landmark markers that can be found in every neighborhood across the city, these traces of history together tell the complex story of how Richmond residents experienced the war.

As the former capital of the Confederacy, it only makes sense that the country’s largest and most in-depth Civil War museum be constructed in Richmond, along the James River at one of the most important sites of the war: Tredegar Iron Works.

Although Tredegar already houses a Civil War museum, the sister museum to the Confederate White House, it is about to undergo a major renovation that will create a new 7,000 square foot gallery space, along with outdoor exhibits, according to a museum press release.

The American Civil War Museum was formed in 2012 with the consolidation of the American Civil War Center at Historic Tredegar and the Museum of the Confederacy. The museum is now run by co-CEOs, S. Waite Rawls III and Christy Coleman. Resident Civil War historian and former president of the University of Richmond, Dr. Edward Ayers, heads the board.

“The new American Civil War Museum at Tredegar will be the best in the nation and will tell the story more fully than anywhere else,” Ayers said.

The new museum will be all about giving the breadth of perspectives from people who experienced the war, Rawls said. In the early 2000s, many museums around the country were presenting the story of the Civil War as “white men fighting white men,” with the African American story as the sidebar, Rawls said. The American Civil War Museum decided to address this problem by creating exhibits aimed at telling “three sides” of the story: the North, the South, and the African Americans.

But now the museum is adjusting their approach again, changing the “three side” concept, which Rawls explained as problematic because it attempted “to take 30 million people and stick them in one of three pigeonholes.” The new approach isn’t confined to three perspectives, but presents many diverse perspectives on the war.

“How about the white guy living in Alabama who didn’t believe in the Confederacy and fought for the Union?” Rawls said, “How about the black woman who lived in Pennsylvania free, and did not want her son to go fight in the Union Army?”

Its examples like these that beg for a museum that shatters preconceived notions.

Just as the stories of Jefferson Davis and his family’s personal experiences in Richmond gave me a new perspective, hopefully the stories that this new museum chooses to tell, will set the standard for what Richmond residents and tourists alike understand about the complexities of the war and their lasting legacy.

“We will never move on, nor should we,” Ayers said. “This is the central event in our nation’s history—and we are the central location to understand it.”

By Brooke Harty