Remnants of a Fulton past peek through the verdure of Gillies Creek Park. Photo by Garrett Fundakowski.

ACROSS THE STREET from the gravel parking lot, a crumbling concrete path leads into the trees. Weeds have grown through the cracks and glass shards litter the spaces in between. Off to the left, a rusted metal dumpster sits silently; small yellow flowers bloom at its base. The sign reads Gillies Creek Park.

In the clearing ahead, two stone steps rise out of the ground leading to an elevated grassy platform. The unmarked brick and concrete foundation is situated in the thoroughfare of Hole #17 on the disc golf course. In its past life, it was situated in a block of brick row houses at 615 State Street. But that was half a century ago.

“Historic Fulton had everything, and when I said we had everything, I mean we had everything,” recounts Rosa Coleman, current president of the Fulton Hill Civic Association. “Groceries on every few streets, corner stores in between, social clubs, churches, doctors, a theater, a bank, a school, and even a funeral home. You never had to leave the community for anything.”

Rosa grew up in Fulton as a little girl in the 50’s. She tells me story after story trying to give life to the aging pictures she shows me of Historic Fulton. She remembers running around in the streets with the neighborhood kids after school while the adults sat on the porch playing dominoes. She recalls the collective community pilgrimage of sundresses and hats to and from Rising Mt. Zion Baptist Church every Sunday.

“We had a close-knit neighborhood. You know that Bible saying, ‘it takes a village to raise a child’?” She laughs as she tells the story of a time she got in trouble for not helping to clean up after dinner at her friend’s house just down the block. As she walked home, she remembers her neighbor coming out to lecture her about respect before she even got home to be punished by her parents. “Fulton was a village.”

But by 1980, everything was gone. And when I say everything, I mean everything.

Longtime Fulton resident, Spencer Armstead, sits atop a barricade. Behind him is what is left of his community. Photo by Tim Wright, Richmond Times-Dispatch, 1980.

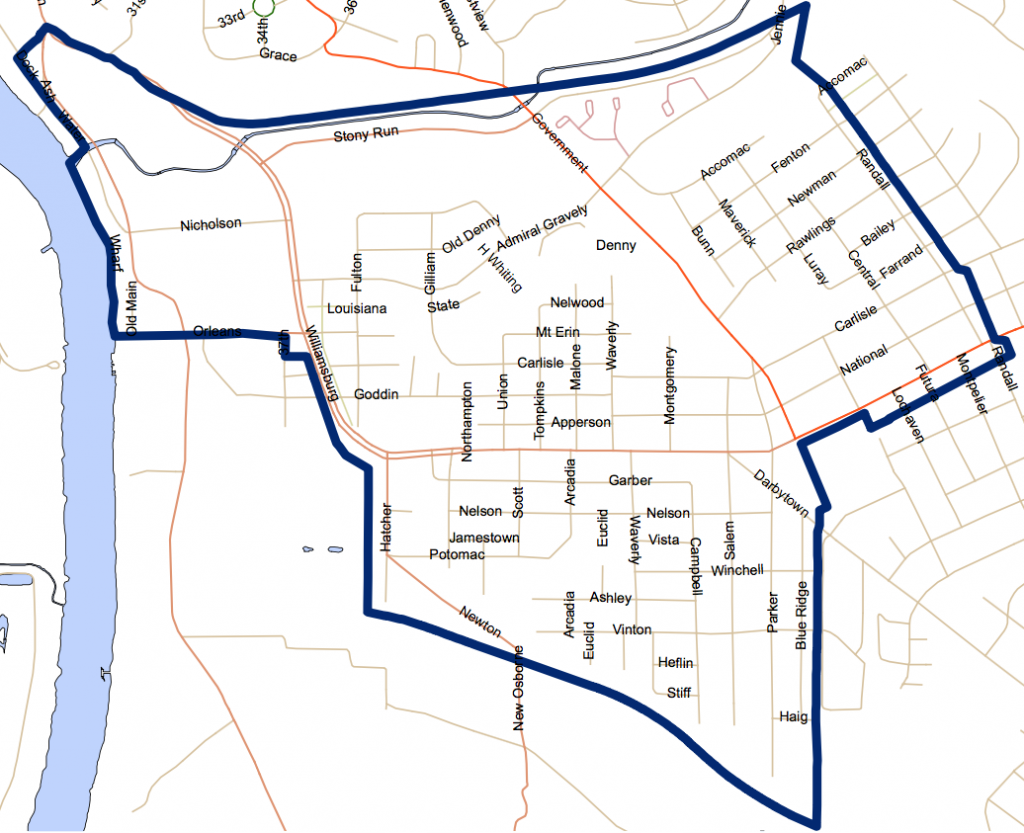

It began in the late 1960’s, when the Richmond Redevelopment and Housing Authority (RRHA) was commissioned by the city council to draft plans for the redevelopment of Fulton. By this time, Fulton was no longer viewed as a prosperous, self-sustaining neighborhood. Instead, in 1969, the Richmond-Times Dispatch cast it as “an aged and ragged neighborhood” and city leaders declared it “Richmond’s worst slum.” Seldon Richardson’s Built By Blacks, African American Architecture and Neighborhoods in Richmond cites the 1972 flood and the arrival of heroin as driving factors of the deterioration of Fulton. Others ascribe it to the influx of poverty that followed the development of the surrounding suburban neighborhoods. Ultimately, it was a combination of factors that lead to degradation of the community.

Over the course of the next decade, under the guise of the Fulton Urban Renewal Program, 785 families were displaced. Schools were shut down, houses were destroyed, and churches and stores were forced to close or relocate. The neighborhood of Fulton and its community was completely demolished. Shattered like the glass shards on the concrete, the people scattered throughout the surrounding neighborhoods.

“We had everything,” Rosa says, her voice faltering as she struggles to quiet her tears. “Then we had nothing.”

The cracked remains of Old Denny Street sit barricaded and overgrown by vegetation . In the background, new houses have been built, but the community is nothing like it once was. Photo by Garrett Fundakowski.

The promised redevelopment of Fulton never materialized. The area sat empty for years. It would be ten years before Gillies Creek Park was established and another two decades before any construction of housing in the area began.

Nowadays, Historic Fulton is hard to find. Its old street grid has been buried beneath the beer tanks and asphalt of Stone Brewing Company. Its old homes have been replaced by a new community of solar-powered villas. While Gillies Creek Park has preserved some of the foundations and old concrete streets, Historic Fulton exists most vibrantly in the memories of its former residents, who still gather on warm summer nights at the Horseshoe Pits just up the trail from 615 State Street.

By Garrett Fundakowski