Bus Stop 191, located at the corner of Admiral Gravely and Government, sits empty in the afternoons. Photo by Garrett Fundakowski.

I TAKE A SEAT ON A BENCH at the corner of Admiral Gravely Boulevard and Government Road in the Fulton community of downtown Richmond. I’m waiting for the bus at Stop 191.

It’s early evening—4:42 pm, to be exact. Behind me, the echo of a basketball smacking asphalt can be heard as two children practice their bounce passes in the streets of D block in Fulton’s 64-unit public housing complex. Across the street, a mother and her daughter walk along a sidewalk that parallels the street before veering off into the wooded area at the easternmost edge of Gillies Creek Park about a hundred yards down.

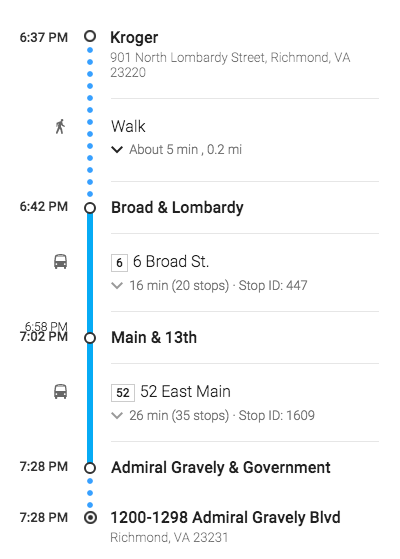

As I wait, I do a quick search on my phone. Let’s go to a grocery store. I find out that the closest one is miles away, either out in the county or all the way uptown on Broad Street (another problem for another day). I use the GRTC Trip Planner and find that a trip to the grocery store requires requires transferring lines and would take just over 2 hours, at a minimum.

For a neighborhood like Fulton Hill, where 44.9 percent of its population lives below the poverty line, many families rely on public transportation to get around town.

“That’s part of the problem,” says Carolyn Loftin, Community Coordinator at Urban Hope, as she takes her turn to speak openly at the public forum following the production of Churchill: A Changing Neighborhood at Armstrong High School.

With the current system, she says, residents of Church Hill and Fulton in particular have limited access to jobs, food, and other necessities, and desperately need reliable transportation to these areas. “[We need] transportation that comes more often than once an hour, transportation that doesn’t stop running at 6:30 in the afternoon to our most impoverished areas.”

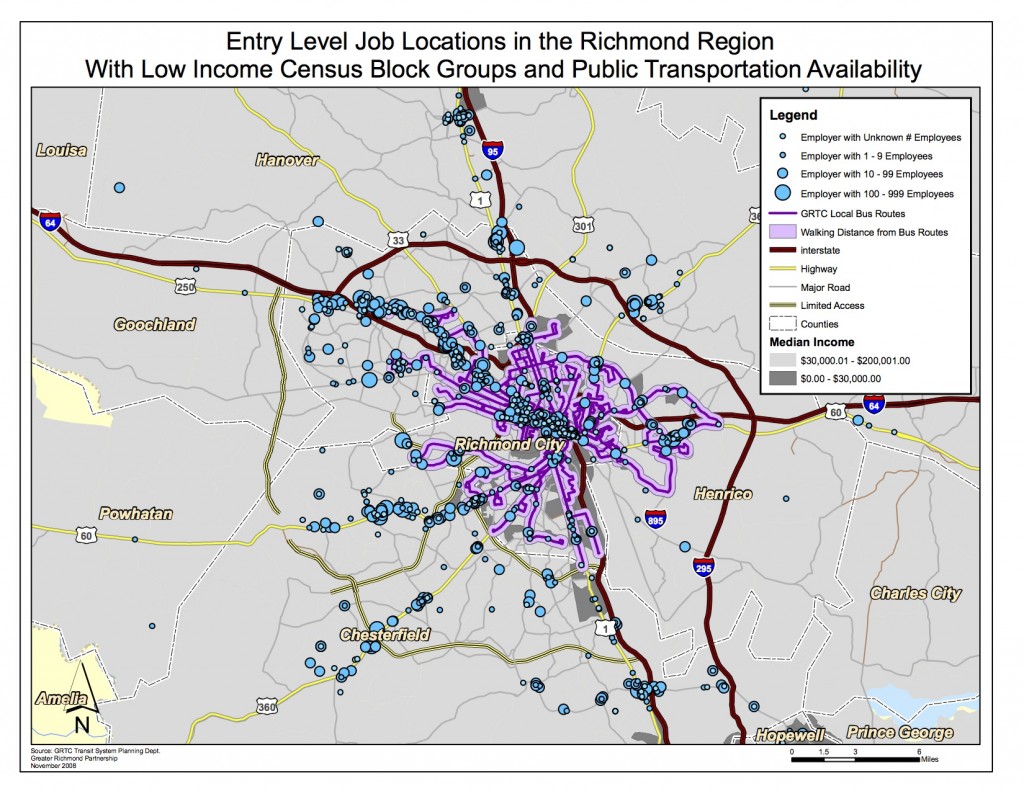

Albert Walker agrees. “The system is broken,” he says. Working out of the East End’s Family Resource Center, Walker, the center’s Healthy Communities Liaison, shows me a map depicting the location of entry-level jobs in relation to public transportation lines. “Where are most of the jobs?” he asks. “Outside the bus routes.”

He cites a 2012 report by the Brookings Institute that placed Richmond as 82nd out of the nation’s 100 largest metropolitan areas in terms of labor’s access to the workplace.

When I bring up the Bus Rapid Transit system the city is working on to help improve transportation in the city, Albert rolls his eyes. He is doubtful that it will solve anything.

Cheryl Groce-Wright, Executive Director at the Neighborhood Resource Center, on the other hand, is optimistic. She talks about the trolley system of the past driving the development of entire sections of the city. “I think there is great potential for the BRT to help [Fulton] out. But the only way the BRT is going to work for this neighborhood is if they put in the connectors to the main line on Orleans Street,” she warns. “But I’m glad that the city and GRTC are talking to residents to find out what they need and really allow them the opportunity to weigh in…We’ve been left to our own devices for so long.”

I’m still waiting. A half hour passes, 45 minutes. A school bus pulls up and students file out before disappearing down the block. A passerby, a man, asks what I’m doing. Together, we watch as Bus 52 drives past without stopping. “If you’re waiting for the bus,” he says, you’re out of luck. “It doesn’t stop here after 12 o’clock.”

By Garrett Fundakowski