An outsider’s view: Clay Abner Park in Richmond’s Jackson Ward, April 24, 2016. Photo by Molly Brind’Amour.

It is a beautiful day at Clay Abner Park, in Richmond’s Jackson Ward neighborhood. I don’t know what I expected from a park in the heart of one of Richmond’s oldest, poorest, and predominately African-American neighborhoods. But it is a perfect Sunday in late April. Spring has swept through the city at last, and the park is teeming with life in the late afternoon.

I sit on a ridge and watch the people go by, humans black and white, of all ages. Families pile out of minivans and hipsters stroll across the slope. Kids race around the playground as a young couple nearby makes out against a tree. Oak leaves cast shadows onto the dirt, as swings squeak and skateboard wheels glide smoothly across blacktop. It feels like a place I went when I was young. It feels like forever.

I decide to break this reverie by striking up a conversation to learn how this park exists in relation to its neighborhood. I walk towards a basketball game and meet two middle-aged black men who stand near a table full of lunch fixings. They are quiet and noncommittal. My attempts at small talk go nowhere. They are there to enjoy their picnic and their game, making me painfully conscious that I’m an outsider. I can’t bring myself to ask about the Civil War or poverty or race, as their world draws them outside the margins of our conversation.

Neighborhood kids come out on Sundays to “play ball,” they say. Jackson Ward is a “quiet neighborhood.” That’s what the men offer me, and before long, they melt back into their surroundings, and I return to my reverie.

I could write about this, the peaceful coexistence of human beings on a beautiful day in a diverse neighborhood. Or I could write about Charles, who sits on the other side of the ridge from me, smoking a cigarette. I’m tempted to call it a day, but instead I introduce myself.

Charles, who doesn’t want me to use his real name, is a few years older than I am and he allows me, after a brief pause, to sit down and ask him questions.

I ask him about the neighborhood. It is “pretty okay, sorta kinda,” he says. He pauses. “I’m black and I’m young. I don’t pay the neighborhood too much attention.” He explains, “I don’t want anyone to feel uncomfortable because of the way I talk, the way I carry myself.”

I don’t exactly feel uncomfortable around him. But I know he’s thinking of people like me: White people, mothers and visitors and policemen, people who see a young black man with tattoos, wearing street clothes and speaking in “ebonics,” and see danger. In light of the murders of Eric Garner, Michael Brown, Tamir Rice, and Freddie Gray—all unarmed black men killed by police, presumably because their blackness was intrinsically threatening—Charles is excruciatingly self-aware.

Within the first few minutes of our timid conversation, I sense him opening up. And then the truth comes out. This is “not a friendly neighborhood,” he says. It was “designed for black people.”

Not for people like me, in other words. I think of 1871, when this was the “shoestring ward” as its boundaries were twisted, stretched, and gerrymandered like shoelaces in every direction to confine Richmond’s newly eligible black voters and deny them electoral power.

Charles’s words sweep and swirl, sometimes overlapping my perceptions, sometimes surprising me. He offers smooth answers to questions I haven’t yet asked, punctuating his remarks with “know what I’m sayin’?” or “just tellin’ it like it is.” He speaks of “a cycle of light and darkness,” of how those with all the knowledge have all the power to keep the rest oppressed. When I nod, he says simply, “That’s government, sweetie.”

He talks of a black underclass deprived of learning, of resources, of everything. To rebel against the predominant lifestyle of his community would be to stand alone, and “nobody wants to be alone.” There’s pressure from every direction to go with the grain. “If I hang around drugs all day…” He trails off. There is “no escape from that life.”

I’m surprised that he’s 24, with all that he’s seen. And he’s surprised that I’m only 19, which seems to reassure him. He’s glad that I’m getting an education, he says, and that I have good parents. He didn’t have people to help him, and wishes that he’d taken a different path at my age. He’s only 24, but he remarks, with brutal honesty, “my time is coming.” For Charles, the world is cold, without mercy.

“History got a lot to do with a lot of shit…Niggas put us in projects, put liquor stores on every corner in the hood.” His words haunt me. “In the eyes of many, we already lost the race.”

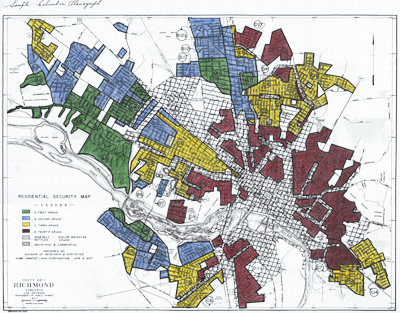

1937 HOLC map of Richmond. Jackson Ward is one of the red areas zoned with the worst grade, “D”, presented as “fully declined.” These predominately African-American “fourth-grade” areas were seen as unsafe for investment and were subsequently starved of funds. Photo credit: University of Richmond

On April 1st, 1865, Confederate General Richard S. Ewell and his command set fire to the food, clothing, and tobacco of Richmond, Virginia. With the Union troops at the door of the capitol, the Confederates set fire to the city’s provisions, as starving civilians watched. Riots broke out, the fires spread, and before long, the capitol was ablaze with a fire that would destroy 54 blocks of the city. The rebel army had destroyed their own city just to keep the enemy from eating. It was one last act of defiance against the inevitable—one last strike in the name of a lost cause.

It is 2016, yet there are people of color here who cannot rise to better circumstances. It is 2016, and in a modern East Coast city in the richest country in the world, maps show a tragic reality: White areas of Richmond are richer, healthier, and better educated. Black areas are poorer, sicker, and less literate.

Richmond’s African Americans were emancipated 150 years ago, followed by reconstruction. Then came the gerrymandering, and in 1888 streetcars began whisking whites out of Richmond’s inner city and into deed-restricted suburbs that would stay white to this day. In 1912, residential segregation became legal, and even after it was ruled unconstitutional, segregation could continue using restrictive covenants and fear-mongering real estate tricks. A few decades later, the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) drew maps (right) deeming black neighborhoods unsafe for investment, followed by the development of public housing projects, I-95’s deadly division of Jackson Ward, gentrification, subprime lending and the foreclosure crisis. A map of today’s Richmond (below) shows that not much has changed.

Charles is right, I realize. This place, the poverty and the segregation, was created. This devastation was deliberate.

I curl up on the #2 Westbound, following the golden sun as I travel from Clay Abner Park past grander houses and bigger lots, back into one of the whitest and richest neighborhoods in Richmond. I chew my straw on the bus, thinking about scorched earth. About the evil people are capable of, when they would rather wreak destruction than allow “the other” to flourish, or even to survive. About how we love to put off the inevitable, destroying out of spite and blind pride and fear of the unknown. Fighting for a lost cause, rather than looking out for fellow human beings.

Charles said something else to me, when I asked him whether the Civil War and slavery are still impacting Richmond. He was incredulous.

“I can’t believe you’re asking that question,” he said, as I looked out onto the sunny, restless streets of Jackson Ward. “It’s right in front of your face.”

by Molly Brind’Amour