This week on Expanding the Ivory Tower we consider two articles, one written in 1973 and the other in 2016, that chronicle black students’ critiques of the university.

Victoria Charles

This Week in the Archive: The HEW Plague

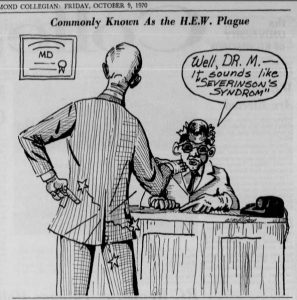

This image appeared in the October 9, 1970 edition of The Collegian, the student newspaper at the University of Richmond. The cartoon depicts Dr. George Modlin, former university president, pointing to what seems to be a pain in his backside. The doctor in the cartoon diagnoses Modlin with a fictional ailment referred to as Severinson’s Syndrome. The image caption explains that the ailment is also “commonly known as the HEW Plague.” In effect, the cartoon implies that Severinson’s Syndrome or the more commonly the HEW Plague is what’s causing the pain in Dr. Modlin’s backside.

This image appeared in the October 9, 1970 edition of The Collegian, the student newspaper at the University of Richmond. The cartoon depicts Dr. George Modlin, former university president, pointing to what seems to be a pain in his backside. The doctor in the cartoon diagnoses Modlin with a fictional ailment referred to as Severinson’s Syndrome. The image caption explains that the ailment is also “commonly known as the HEW Plague.” In effect, the cartoon implies that Severinson’s Syndrome or the more commonly the HEW Plague is what’s causing the pain in Dr. Modlin’s backside.

Severinson’s Syndrome alludes to Dr. Eloise Severinson, the regional civil rights director for the now-defunct Department of Health, Education and Welfare (HEW). Appointed to the position in 1968, Dr. Severinson was tasked with helping institutions comply with Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which prohibited discrimination on the basis of race, color, or national origin in any program receiving federal funding. In October of 1970 Dr. Severinson wrote a letter to Dr. Modlin expressing her belief that the University of Richmond still projected “an image of an exclusive all-white Southern institution.” Since the University had begun accepting federal aid several years prior, Severinson maintained that HEW could stop funding the University if it was not in compliance with the law. In the letter Severinson offered numerous solutions to the problem including the admission of more high-risk students, the hiring of black administrators, and cooperation with historically black colleges and universities in the area such as Virginia Union University. Severinson also advocated the use of more black students in the recruitment process along with an augmented interest in recruiting blacks students.

President Modlin declined to comment on the subject of the letter and instead told the Richmond Times-Dispatch that he would “take the matter up with the board of trustees later” in the month. The cartoon reflected student perception of Modlin’s lackadaisical attitude toward Severinson’s letter. His lack of comment made it seem as though the letter served as an annoyance to be ignored rather than an impassioned call to action. Further, Modlin’s complicit acceptance of the racial status quo at the University was inherently racist because it effectively shut minorities out of educational opportunities. His silence on the matter actually speaks volumes to the lack of commitment to racial equity on the part of university administrators at the time. They essentially had to be strong-armed into compliance with the Civil Rights Act and when prodded they erred on the side of inaction.

Behind the Pine Curtain

This week on Expanding the Ivory Tower Victoria examines the context surrounding Black Student Day, a 1971 student-led event aimed toward achieving a more diverse student body. In this episode she raises questions about intent and challenges the assertion that the impetus for the event stemmed solely from goodwill.

This Week in the Archive: Confederate Spidey

This image is a snapshot of the cover of the 1960 edition of The Web, the University of Richmond’s former yearbook. The cover features Confederate Spidey, who at the time was described as the University’s unofficial mascot. Dressed as a Confederate soldier and armed with a sword and a musket, the illustrated spider is also carrying a Confederate flag on the cover. Although Confederate Spidey makes thirty appearances in the yearbook there is no explanation of why the image is used so frequently in the two-hundred-page publication. The foreword simply reads, “may these pages hold many happy memories for you.”

It is possible that the copious use of the image in the 1960 edition was a nod to the impending centennial Civil War celebrations in Richmond. However such a gesture would have been more fitting to include in the 1961 edition of The Web during the actual centennial. So let’s consider for a moment that the imagery in the yearbook has little to do with the celebrations. The student editors, Richard Brewer and Betty Pritchett, had to have assumed that Confederate Spidey’s image could stand devoid of context in a university publication. Yet that assumption calls into question the extent to which Confederate Spidey was in fact an unofficial mascot of the University. If the students in charge of publishing a piece that represented the University to its student body saw no point in explaining the image’s use and used the image so frequently then it seems that the image was only unofficial in name but not in deed.

For a University of Richmond student in 1960 to be able to pick up a copy of the yearbook, simply shrug at the cover, and flip through its pages without considering the implications of Confederate Spidey means a few things. It means that the University was a place where such imagery was common. It means that the University was a place where students welcomed the idea of being represented by a mascot dressed as a Confederate. It means that voices in the campus community that may have been opposed to the imagery were not in the majority. It means that eleven years later when students asked the University Band to restrain its use of the song Dixie there was backlash.

Whenever Confederate Spidey is mentioned in the archive it’s noted that its use was unofficial. It seems that the word unofficial is used to absolve the University’s compliance in its use of racist imagery. Simply because Confederate Spidey was not inscribed on the University mace does not mean that the image did not come to represent the university as a whole. Confederate Spidey mattered to campus culture and touting its “unofficial’ use does not wash away the stain of racism from the University’s cloak.

The “Dixie” Question

This week on Expanding the Ivory Tower Victoria explores a 1971 controversy surrounding the now-defunct University Band’s use of the song “Dixie” during football games. For weeks, a spirited debate concerning the song’s use lined the pages of The Collegian and what unfolds on those pages sheds light on the racial attitudes of students at the time in interesting yet unsurprising ways.

Where Are We Now?

This week our Post-Baccalaureate fellow, Victoria Charles, takes to the studio with her podcast, Expanding the Ivory Tower, to discuss her relationship to Race & Racism at the University of Richmond. She dives into how her research fits into the project and gives us a glimpse into its inception. Victoria also chats with Project Archivist Irina Rogova about Irina’s point of entry and goals for the project.