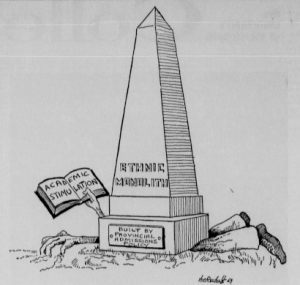

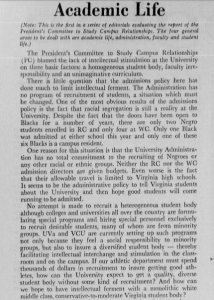

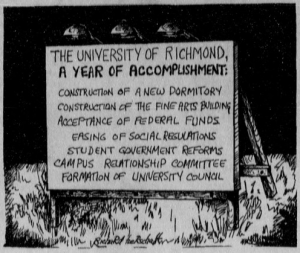

The end of a year, whether that be calendar or academic, is often framed as cause for reflection. Yet end-of-the-year roundups do more than just look back. They consider the defining events of the year through the lens of whoever is writing. Those musings say as much about the events of the year as they do the positionality of the writer. When we take a look at what is included and more importantly what is left out we can unearth valuable subtext. Opportunely, this method applies to archival work as well. Take for example this cartoon published in The Collegian on May 17, 1968. The image depicts signage that reads “The University of Richmond, A Year of Accomplishment”. The cartoonist chose to frame what he deemed the most significant events of the academic year as accomplishments. The claim to accomplishments begs the question, accomplishments for whom? If we take a closer look at the first three: the construction of a new dormitory, the construction of the fine arts building, and the acceptance of federal funds, the answer to that question becomes complex.

The end of a year, whether that be calendar or academic, is often framed as cause for reflection. Yet end-of-the-year roundups do more than just look back. They consider the defining events of the year through the lens of whoever is writing. Those musings say as much about the events of the year as they do the positionality of the writer. When we take a look at what is included and more importantly what is left out we can unearth valuable subtext. Opportunely, this method applies to archival work as well. Take for example this cartoon published in The Collegian on May 17, 1968. The image depicts signage that reads “The University of Richmond, A Year of Accomplishment”. The cartoonist chose to frame what he deemed the most significant events of the academic year as accomplishments. The claim to accomplishments begs the question, accomplishments for whom? If we take a closer look at the first three: the construction of a new dormitory, the construction of the fine arts building, and the acceptance of federal funds, the answer to that question becomes complex.

The construction of the new dormitory was important because some students had been living in temporary barracks that were pre-war, hazardous, and prone to fire. However, this new housing option was only available to male students despite the fact that female students were also in need of improved housing. In fact, an editorial published in the same Collegian issue as this cartoon lamented the overcrowding and lack of amenities available in one of the main residence halls for women. The construction of the fine arts building symbolized a triumph of fundraising and dedication to the advancement of the arts at the University. The construction of the building also underscored the problem of the University paying its workers too little. In fact, work on the building was halted by a worker’s strike started by laborers at the heating plant. Electricians working in the fine arts building participated in the strike as a sign of solidarity with the heating plant workers. The strike eventually ended but did not result in higher wages for the workers. The acceptance of federal funds meant that more money would be available for use other than capital construction but also meant that the University had to comply with federal statutes such as the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which prohibited discrimination on the basis of race, color, or national origin in any program receiving federal funds. Despite having integrated downtown night courses in 1964, the University of Richmond remained segregated on its main campus until the fall of 1968, months after this cartoon was published.

The cartoonist chose to portray the year as one of progress without acknowledging the tenuous nature of the accomplishments he highlighted. He failed to consider that what was good for some was, in fact, harmful to others, that his purview of accomplishments and progress existed in a space where black students had not yet been welcome.