By Hunter Moyler

Long gone are the days when my millennial mind could assume it to be common knowledge, but it remains a verifiable fact: When you mix politics and prejudice, you get stupid. Evidence of this is conspicuous in modern America and, according to many, infuriatingly unavoidable. However, to avoid stepping on the toes of the living, let us turn to the history of political borders right here in the Commonwealth of Virginia in order to illustrate this phenomenon.

Even this early into my research into how structural racism has shaped the Richmond region, I’ve already learned some tremendously interesting information about the effects institutionalized prejudice has wrought. Perhaps most interesting is the fact that my hometown exists largely because there were white parents in the 1960s who didn’t want their children to go to school with black people — and that Richmond’s current boundaries are in part attributable to the same reason.

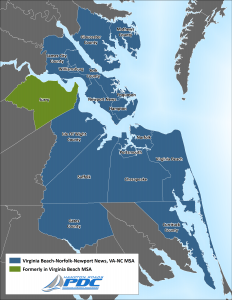

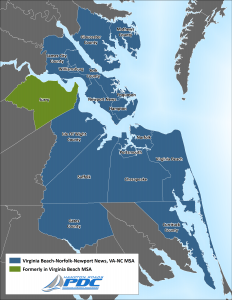

See, in the part of Virginia I grew up in, South Hampton Roads, most people don’t live in counties. The majority of the region is constructed of “independent cities” that all border each other, crammed into the commonwealth’s southeast corner like too many pickles in the same jar. Three of these — Chesapeake, Suffolk, and Virginia Beach — are veritably massive by city standards. The biggest has an area over one hundred square miles larger than New York and more than twice as large as Chicago. Below is a map of the area. That these county-sized swaths of land are considered mere “cities” is completely ludicrous. To use the aforementioned term, I think it might be a smidge stupid.

I’ll explain: In my research this summer, I’ve read excerpts from Richmond’s Unhealed History, a book by Dr. Benjamin Campbell on the history of racial prejudice (the lion’s share of which was government-sanctioned) in and around the city. In the chapter, “Massive Resistance and Resegregation,” the author details the plethora of legal and legislative hoops the Virginia General Assembly leapt through to defy the federal government’s mandate to integrate public schools after the principle of “separate but equal” was ruled unconstitutional in 1954’s Supreme Court ruling in Brown v. Board.

Dr. Campbell writes that part of this Massive Resistance included a “massive retooling of the jurisdictional lines in Virginia and of the laws governing metropolitan areas.” (Campbell 168) Oh, boy. So how did they do it?

Politicians used “white flight” to their advantage. This refers to the mid-century trend of white families to leave the inner city for the suburbs, in part so they could keep their children out of school districts with substantial black populations. By 1960, for example, most white families in the Richmond metro did not live in the city proper, but rather in the surrounding counties of Henrico and Chesterfield. (Campbell 168) The same was true for Hampton Roads in that decade: The city of Norfolk had a large black population, but one dwarfed by the white populations of surrounding counties. (Campbell 169)

Norfolk and Richmond were growing, as cities tend to do. Because they were independent cities, they were able to annex portions of their surrounding counties. Some white people in these counties didn’t want to be annexed, though. Not only would their children now be within the boundaries of majority-black school districts, but their voting power as the racial majority would be greatly diminished.

Counties in Hampton Roads were so fearful of annexation that they turned to a provision in the Virginia constitution to keep safe from it. According to the constitution, independent cities could annex land from counties, but not other independent cities. So, naturally, the majority-white statesmen and citizens from the counties surrounding Norfolk scrambled to re-establish themselves as independent cities to avoid annexation. (Campbell 169) The General Assembly, of course, was compliant, resulting in Hampton Roads’s current silly city divisions. This paranoid fear of black people is why Virginia Beach, Suffolk, and my beloved Chesapeake exist, and also why they’re the size of counties.

In Richmond, the approach was a bit different. Since the city was growing, it did indeed attempt to annex parts of the surrounding counties and achieved some success. But instead of allowing, say, Henrico County to consolidate into the City of Henrico, the General Assembly opted to place restrictions specifically on the City of Richmond. In 1971, it bizarrely prohibited the city from annexing any land from the surrounding counties. (Campbell 173)

I found this information jarring. I was aware of the far-reaching effects of structural racism, but I would not have guessed that it was directly responsible for the very borders of my hometown and my adopted city. This history permeates the state, and to this day still factors into where people go to school and, subsequently with whom they associate.

Campbell writes that “The troubles that still afflict the culture of metropolitan Richmond have their roots in problems long denied, changes not attempted, prophecy unheeded, [and] injustice unacknowledged.” I’m not sure how well-known these facts about redrawing political lines are around the state, but I know I can’t have been the only person unaware. Naturally, this history must be confronted if it is to ever be reconciled, which is why I believe the Race & Racism Project and Untold RVA’s work is vital.

Hunter Moyler was raised in Chesapeake, Virginia. He is a rising junior at the University of Richmond, double-majoring in English and Journalism with a minor in Spanish. He is vice president of the College Democrats at the University of Richmond and co-editor of the Opinions section in The Collegian. This summer, he’s elated to have the opportunity to delve into the history of race relations in his state thanks to an A&S Summer Research Fellowship.