This week on Expanding the Ivory Tower Victoria critiques her own research and the practice of working in isolation from the communities she studies.

Uncategorized

This Week in the Archive: Aron Stewart Day

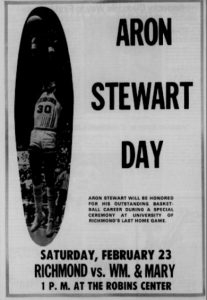

This announcement for Aron Stewart Day, scheduled for February 23, 1974, publicized the celebration of Aron Stewart (R’74) “for his outstanding basketball career during a special ceremony at [the] University of Richmond’s last home game” against William and Mary. Held during halftime, the ceremony lauded his accomplishments on the court before thousands of cheering fans in the newly minted Robins Center. University of Richmond President E. Bruce Heilman, Richmond City mayor Richard Bailey and former UR coach and athletic director Malcolm “Mac” Pitt, took turns praising Stewart’s career. During the ostentatious affair a letter from Governor Mills Godwin was read, Dr. Heilman presented Stewart with a trophy, and the crowd of over 5,000 fans gave him a rousing ovation.

This announcement for Aron Stewart Day, scheduled for February 23, 1974, publicized the celebration of Aron Stewart (R’74) “for his outstanding basketball career during a special ceremony at [the] University of Richmond’s last home game” against William and Mary. Held during halftime, the ceremony lauded his accomplishments on the court before thousands of cheering fans in the newly minted Robins Center. University of Richmond President E. Bruce Heilman, Richmond City mayor Richard Bailey and former UR coach and athletic director Malcolm “Mac” Pitt, took turns praising Stewart’s career. During the ostentatious affair a letter from Governor Mills Godwin was read, Dr. Heilman presented Stewart with a trophy, and the crowd of over 5,000 fans gave him a rousing ovation.

Aron Stewart, the second black student-athlete to sign with the men’s basketball team (after Carlton Mack in 1970), transferred to the University of Richmond from Temple in 1972. The Jersey City, New Jersey native started off his collegiate career at Essex County Community College where he was a junior college All-American and also led the nation in scoring. After becoming eligible to play at the University of Richmond, Stewart rescued the basketball team from ruins. In his first six games alone Stewart helped the team pick up three wins in what had up to that point been a winless stretch. Throughout his two seasons with the Spiders Stewart almost always led the team in scoring and collected various accolades. In the ’72-’73 season he was named the Southern Conference player of the year, finished fourth in the nation with a 30.3 scoring average and broke numerous all-time records at the University. The following season he was named Southern Conference MVP and chosen as a Helms Foundation All-American.

Coverage of Stewart in The Collegian focused on his time on the court and rarely extended to his identity as a black student on campus with the exception of two occasions. In the first, he is discussed in an article about how much black student-athletes have to offer University of Richmond athletics. In the other, he is quoted at the very end of an article about the prestige that he brought to athletics as saying “blacks have no say on this campus.” The near exclusion of Stewart in the discourse surrounding black students at the University is odd because at the time black students were still new to campus and much of their coverage in The Collegian centered on their struggle for inclusion in the mainstream. Both athlete and non-athlete black students were viewed through this lens yet Stewart all but escapes such consideration. It is possible that his status as a campus superstar allowed for those writing to overlook that part of his identity and let his talent transcend his race. In that way, Aron Stewart, the black student-athlete, becomes Aron Stewart, big (raceless) man on campus.

My Chat with Iria Jones

This week’s episode of Expanding the Ivory Tower captures part of a conversation with an alumna whose pathway to the University of Richmond intertwines with the university’s legacy of racial discrimination.

This Week in the Archive: Deborah Snaggs and Black Women Student-Athletes

The term black student-athlete is laden with gendered understandings. Colloquially, the term is most often used as shorthand for black students on the men’s football or basketball team at any given university. That usage not only dismisses the diversity of talent black men student-athletes provide to athletics beyond the realm of football and basketball but also erases the experiences of black women student-athletes and their contributions to athletics.

Even within a historical context, the argument that black student-athletes were central to the integration of predominately white institutions in the 1960s and 70s is one that exclusively relies on the experiences of black men. Part of the narrowness of that argument can be attributed to the lack of emphasis placed on women’s athletics in general. More specifically the limitations of that argument also relate to the timing of the passage of Title IX legislation. Title IX as part of the United States Education Amendments of 1972 states, in part, that “no person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.” Title IX expanded educational access and opportunities to women particularly in relation to collegiate athletics.

However, the measure came into law after the big waves of integration at predominately white universities had occurred so black women student-athletes were not as integral to that process as black men athletes. Even more, there was significantly less money and attention coming out of women’s athletics so universities placed less importance on recruiting women athletes. In fact, the University of Richmond, despite a long history of having women’s athletics, did not reward a full athletic scholarship to a woman (black or white) until 1981. That scholarship went to Jo White, a white woman on the cross-country team. White was a talented runner that excited the campus community and continued a legacy of excellence on the women’s cross-country team arguably started by Deborah Snaggs, a 1981 Westhampton College graduate.

However, the measure came into law after the big waves of integration at predominately white universities had occurred so black women student-athletes were not as integral to that process as black men athletes. Even more, there was significantly less money and attention coming out of women’s athletics so universities placed less importance on recruiting women athletes. In fact, the University of Richmond, despite a long history of having women’s athletics, did not reward a full athletic scholarship to a woman (black or white) until 1981. That scholarship went to Jo White, a white woman on the cross-country team. White was a talented runner that excited the campus community and continued a legacy of excellence on the women’s cross-country team arguably started by Deborah Snaggs, a 1981 Westhampton College graduate.

Snaggs, a black woman, had transferred to the University from Delaware State in 1977. Within her first year, Snaggs had qualified for the Association for Intercollegiate Athletics for Women Championship in the 5000-meter race and “led an assault on the record books [by] setting ten new marks in the State Championship Meet” in 1978. She won numerous state titles and set many school records during her time at the university. Inducted into the Hall of Fame in 1990, Snaggs is regarded as “one of UR’s all-time great track student-athletes.”

Run, Jump, and Shoot

Inspired by a presentation given during Black History Month by a group of black student-athletes entitled “Reflections of Our Past”, I return to an earlier episode about the importance of black student-athletes to the history of predominately white institutions and more specifically to the history of the University of Richmond. “Reflections of Our Past” not only presented an expansive history of black athletes in the United States but also posited the role of black athletes (both student and otherwise) in today’s political climate as that of influencers and change agents.

Sitting in the audience I could not help but think back to this episode and my musings about black student-athletes and their significance to the integration of predominately white universities in the 1960s and 1970s. I described black student-athletes as the “vanguards of black student life on campus” because they often cleared the way for further integration at many institutions. As you listen you may be struck by the absence of black women student-athletes in the narrative, which is an unintended consequence of their exclusion from the historical record. With a more intentional eye I plan to uncover their stories and consider their contributions to the university community and legacy.

This Week in the Archive: Joyce Faison Memo

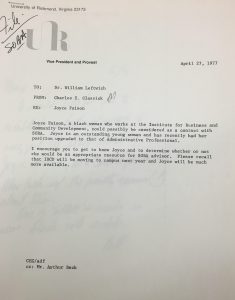

On April 27, 1977, university provost, Dr. Charles Glassick, sent a short memo to the then-vice president of student affairs, William Leftwich, about Joyce Faison. Faison was a black woman, who worked for the Institute for Business and Community Development. The university-sponsored institute was located downtown on Grace and Lombardy Streets and started in 1963 to help resolve issues between businesses and communities with higher education resources. At the time, Faison had recently been promoted to an administrative professional position at the institute and Glassick believed that she could be “considered as a contact for SOBA (Student Organization for Black Awareness).” Glassick goes on to prompt Leftwich to reach out to Faison and determine whether she would be a suitable sponsor for SOBA. Glassick also mentioned that the Institute for Business and Community Development was moving to campus the following year and implied that Faison would be more available to them.

On April 27, 1977, university provost, Dr. Charles Glassick, sent a short memo to the then-vice president of student affairs, William Leftwich, about Joyce Faison. Faison was a black woman, who worked for the Institute for Business and Community Development. The university-sponsored institute was located downtown on Grace and Lombardy Streets and started in 1963 to help resolve issues between businesses and communities with higher education resources. At the time, Faison had recently been promoted to an administrative professional position at the institute and Glassick believed that she could be “considered as a contact for SOBA (Student Organization for Black Awareness).” Glassick goes on to prompt Leftwich to reach out to Faison and determine whether she would be a suitable sponsor for SOBA. Glassick also mentioned that the Institute for Business and Community Development was moving to campus the following year and implied that Faison would be more available to them.

On the surface, Dr. Glassick’s memo reads like a good faith effort from the administration to help SOBA advance their organizational aims but the message actually underscores larger institutional problems. Having to look to Joyce Faison, an administrator at an off-campus university-affiliated program, as a sponsor for SOBA points to the lack of black mentors on campus. White men held most high-level administrative positions and the only black faculty member was Dr. Lorenzo Simpson, a professor in the philosophy department, who joined the university in 1976. During this time black students were still fairly new to campus and that was evident in the lack of support from administrators. Instead of being provided guidance, black students had to advocate for it. The black students in SOBA had to prod the administration to make moves forward on their behalf. Black students had to bear the burden of advocacy and simply existing in a majority white space. They were stretched thin and their organization suffered as a result. SOBA members often lamented having to alter their schedule of events due to lack of resources and low attendance.

This document represents the troubling incongruity between a university that wanted to recruit black students but barely supported the black students that were already there. Black students reported that administrators sympathized with them but had no plan for creating an actual infrastructure of support. Administrators had to look for someone off campus to find a mentor for SOBA because there were so few options on campus. However, there is also no indication that Faison asked to sponsor the students but rather an assumption that because she was black she would be up for the job. They had assumed domain over her labor. It is not clear if Faison became a mentor or if the contact was ever made between her and Leftwich but what is clear and in the record is that black students carried the burden of advocating with an administration that was reactive instead of proactive to their needs.

She Persisted and Thrived

On this week’s episode, we consider the story of Irene Ebhomielen, a Nigerian international student who attended the University of Richmond in the early 70s.

This Week in the Archive: Stream of Student Life Cartoon

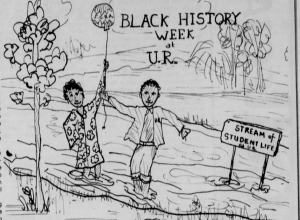

This cartoon accompanied an article entitled “SOBA Moves Toward the Mainstream.” Published in The Collegian on January 31, 1974, the piece concerns the Student Organization for Black Awareness (SOBA), a student group started in 1972 whose purpose, according to the article, was to “make black students an important part of campus life.” The cartoon shows a person in a UR emblazoned suit jacket leading another person holding a balloon labeled “S.O.B.A” into a body of water marked as the “Stream of Student Life at U.R.”. The image seems to rely on an assumption that black students at the university were not part of the norm. That acknowledgment of difference does not honor the diversity of experience black students brought to the university community but rather posits them as outsiders that needed to be led into the mainstream. If the author of the article and the creator of the cartoon had thought more carefully and more empathetically about the fact that simply because black students attended the university they should have been worthy of consideration as part of the mainstream. As full-time students who lived and attended classes, they were in effect part of mainstream university life.

This cartoon accompanied an article entitled “SOBA Moves Toward the Mainstream.” Published in The Collegian on January 31, 1974, the piece concerns the Student Organization for Black Awareness (SOBA), a student group started in 1972 whose purpose, according to the article, was to “make black students an important part of campus life.” The cartoon shows a person in a UR emblazoned suit jacket leading another person holding a balloon labeled “S.O.B.A” into a body of water marked as the “Stream of Student Life at U.R.”. The image seems to rely on an assumption that black students at the university were not part of the norm. That acknowledgment of difference does not honor the diversity of experience black students brought to the university community but rather posits them as outsiders that needed to be led into the mainstream. If the author of the article and the creator of the cartoon had thought more carefully and more empathetically about the fact that simply because black students attended the university they should have been worthy of consideration as part of the mainstream. As full-time students who lived and attended classes, they were in effect part of mainstream university life.

By creating and being part of a student organization SOBA members participated in a mainstream university activity. They went through the proper channels and had a faculty sponsor as well as a budget and a plan for future events just like other student groups on campus at the time. Even the way the founding members framed SOBA in the media was as a non-separatist group that wanted to be integral to all parts of the campus community. Furthermore, within the membership of SOBA, there were individuals who were part of other university entities that were more likely to be considered mainstream activity. For example, Stanley Davis, SOBA’s first president was a Richmond College Student Government Association senator and Norman Williams, the group’s treasurer, was on the track team.

I think the intent of the cartoon was to be welcoming and open-minded but the effect was tone deaf and showed how unfamiliar other students were with black students. The cartoon shows that there were those who were sympathetic to the plight of black students but the way they framed black students’ presence on campus was ultimately harmful because it made it seem like they were other. I understand how that framing might have fit better with a white student’s view of reality but by being full-time students engaged in the campus community in a number of ways it seems to me that black students were already integral to it. However, black students used this language as well which again I think was harmful to their purposes but the decision to adopt that language might have been strategic since they probably knew that others were apprehensive about their presence on campus.

The Circus of Integration

This week on Expanding the Ivory Tower we consider the complicated history of integration at the University.

This Week in the Archive: “May Be Archival Material…”

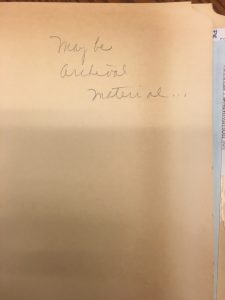

Etched in pencil on the manila folder containing the University records for the Student Organization for Black Awareness or SOBA are the words “may be archival material.” Followed by an ellipsis, those words serve as the entry point for materials concerning a group started in 1973 by black students who hoped to incorporate themselves into the university community. Their first treasurer, Norman Williams, is quoted in The Collegian as saying “‘we hope that by forming this club we can become more of a part of this university and not just another club. We want to take part in University affairs, helping out in any way we can.’” Williams and other members of SOBA emphasized that they did not intend for the group to be separatist. Instead, the founders hoped that SOBA would help black students be significantly involved in university activities. Rather than having one or two students be tokens of the community, members of the group could stand in solidarity with each other and participate in mainstream activities together.

Etched in pencil on the manila folder containing the University records for the Student Organization for Black Awareness or SOBA are the words “may be archival material.” Followed by an ellipsis, those words serve as the entry point for materials concerning a group started in 1973 by black students who hoped to incorporate themselves into the university community. Their first treasurer, Norman Williams, is quoted in The Collegian as saying “‘we hope that by forming this club we can become more of a part of this university and not just another club. We want to take part in University affairs, helping out in any way we can.’” Williams and other members of SOBA emphasized that they did not intend for the group to be separatist. Instead, the founders hoped that SOBA would help black students be significantly involved in university activities. Rather than having one or two students be tokens of the community, members of the group could stand in solidarity with each other and participate in mainstream activities together.

SOBA was formed five years after the arrival of the University’s first black residential student, Barry Greene, in 1968. At the time black students made up less than one percent of the entire student body and struggled for inclusion. At that point, the university administration had not created an infrastructure to support their needs as a minority group on campus. The black students’ decision to form SOBA did not exist in a vacuum but rather in the context of other black students that desegregated predominately white institutions across the country in the late 60s and early 70s who formed similar groups. SOBA’s first president, Stanley Davis, claimed that the group sought to “make students on campus aware about blacks and what they stand for.” They adopted the language of assimilation in order to carve out a space for themselves on the university landscape that they palpably felt did not exist.

The aforementioned folder containing documents related to SOBA primarily includes correspondence between university administrators about the group. The correspondence takes on an apprehensive tone that reflects the hesitance administrators had in dealing with SOBA. In one memo, President Heilman worried the group would take on an adversarial role and in another William Leftwich, vice president of student affairs, feared the group lacked “real purpose and goals.” Other documents containing marginalia note black student suggestions for space for SOBA in the Commons and meetings with administrators. Had these documents not been archived we would have lost the record of these relations. We would have lost the background and context for events that matter to the narrative of SOBA’s existence. The fact that someone would question the enduring value of these documents underscores a larger problem with traditional archives writ large. The voices of marginalized people are not viewed as worthy enough for preservation. This case is a bit different because the voices of SOBA members are not explicitly present but the documents still provide context for the group’s formation and its relation to university administrators.