by Dominique Harrington

When I’ve attempted to explain to people what I’ve been doing this summer, I’ve gotten a few typical responses. First, I get the generic, “That’s so cool! Good luck!” The next one provokes more of a conversation, “That’s interesting, but what’s the point?” However, the response I’ve received most frequently is, “Wow, that must be pretty depressing!” When I explain that I am grappling with the University of Richmond’s racial history, I think they probably thought that I would be faced with more violent instances of racism during the Jim Crow era. However, I’ve mostly gone through letters to President Modlin and Academic Departmental Reports; I haven’t witnessed anything as egregious as one might expect in the former capital of the Confederacy from 1946-1971. Still, I’ve found myself quite disheartened more times than I anticipated — not because of what I saw, but because of what I didn’t see: progress.

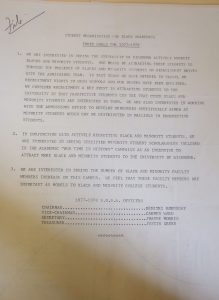

As a current black student at the University, one document in particular exemplified just how much progress we haven’t achieved. In the fall of 1977, Students Organizing for Black Awareness (SOBA) recorded their three goals for the 1977-1978 academic year which centered around recruiting more black students and faculty (click here to see a full description of this archival document).

SOBA was founded in 1974, just six years after the University of Richmond accepted its first black student, Barry Greene, on its main campus. In a Collegian article, “Blacks Seek to “Become a Part,” a quote from SOBA Chairman Stanley Davis stuck with me. He said, “We got tired of waiting around to be incorporated into the University, so we are incorporating ourselves.”

They were tired then, and we are still tired today. Starting with SOBA’s list of goals, it seems as if representation is still one of the biggest issues for which multicultural organizations on campus are advocating. The University of Richmond prides itself on its diversity. When I was a prospective student, I consistently heard speakers boast about “26%”- the percentage of American students of color on campus. However, it certainly doesn’t feel like students of color comprise that large of a portion of campus — especially for black students, because that number is less than ten percent. Regarding faculty, professors of color are still few and far between. Students of color are still tired of waiting to be incorporated, and thus, we are still constantly trying to insert ourselves both in and out of the classroom. The same issues black students were facing then, black students are still facing today.

I won’t claim that the University hasn’t progressed at all, or even that all black students have the same experience. Yes, the number of black students on campus has significantly increased, and there are certainly more faculty of color. However, I don’t believe that numbers that are as a good of an indication of progress as we make them out to be. Although it is great that the number of black students has increased, to me, that number is irrelevant since black students still feel similarly unsafe and left out as their predecessors did.

As I’ve noted in previous posts, progress isn’t linear at all. I suppose that’s why I’ve been so disappointed during my summer experience. Each time I went to the archive or a site, I naively expected to be able to derive some progress from that experience. Obviously, that’s not what happened. When I learned about SOBA, I expected to find pride in how far the black student community has come since black students were first accepted on campus. Instead, I found that black students are still asking for the exact same things, and having the exact same conversations.

An activist and Youtuber, Kat Blaque, that we engaged with during a team meeting claimed that guilt is useless. To me, disappointment without action is just like guilt. Therefore, instead of dwelling in my unreached expectations, I’ll continue following SOBA’s lead- incorporating myself in an institution not meant for me and carving out space for those like me — both historically and in the present. As Frederick Douglass once said, “Without struggle, there is no progress.” However, my only qualm is that it seems as if some would claim that a significant component of the black experience has been exactly that-struggling. When exactly will progress catch up to the struggle? To me, we aren’t there yet — not even close.

For more information:

Lassiter, Jay. “Blacks Seek to ‘Become a Part” The Collegian. 31 January 1974. http://collegian.richmond.edu/cgi-bin/richmond?a=d&d=COL19740131.2.2&srpos=1&e=–1968—1978–en-20–1-byDA-txt-txIN-

“The Absence Of A Black Social Life” The Collegian. 1 October 1971. http://collegian.richmond.edu/cgi-bin/richmond?a=d&d=COL19711001.2.8&srpos=6&e=–1968—1979–en-20–1–txt-txIN-

Dominique “Dom” Harrington is a junior majoring in American Studies and minoring in Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies. She worked with the Race & Racism project for the Fall 2016 seminar, Digital Memory and the Archive. This summer, she was thrilled to continue working with this project remotely from her hometown of Indianapolis, Indiana.