by Gabby Kiser

Gabby Kiser is a junior from Williamsburg, Virginia majoring in English and minoring in History. This is her first summer with the Race & Racism Project. She is also the general manager of WDCE 90.1 FM, a design editor for The Messenger, and a Bunk content wrangler.

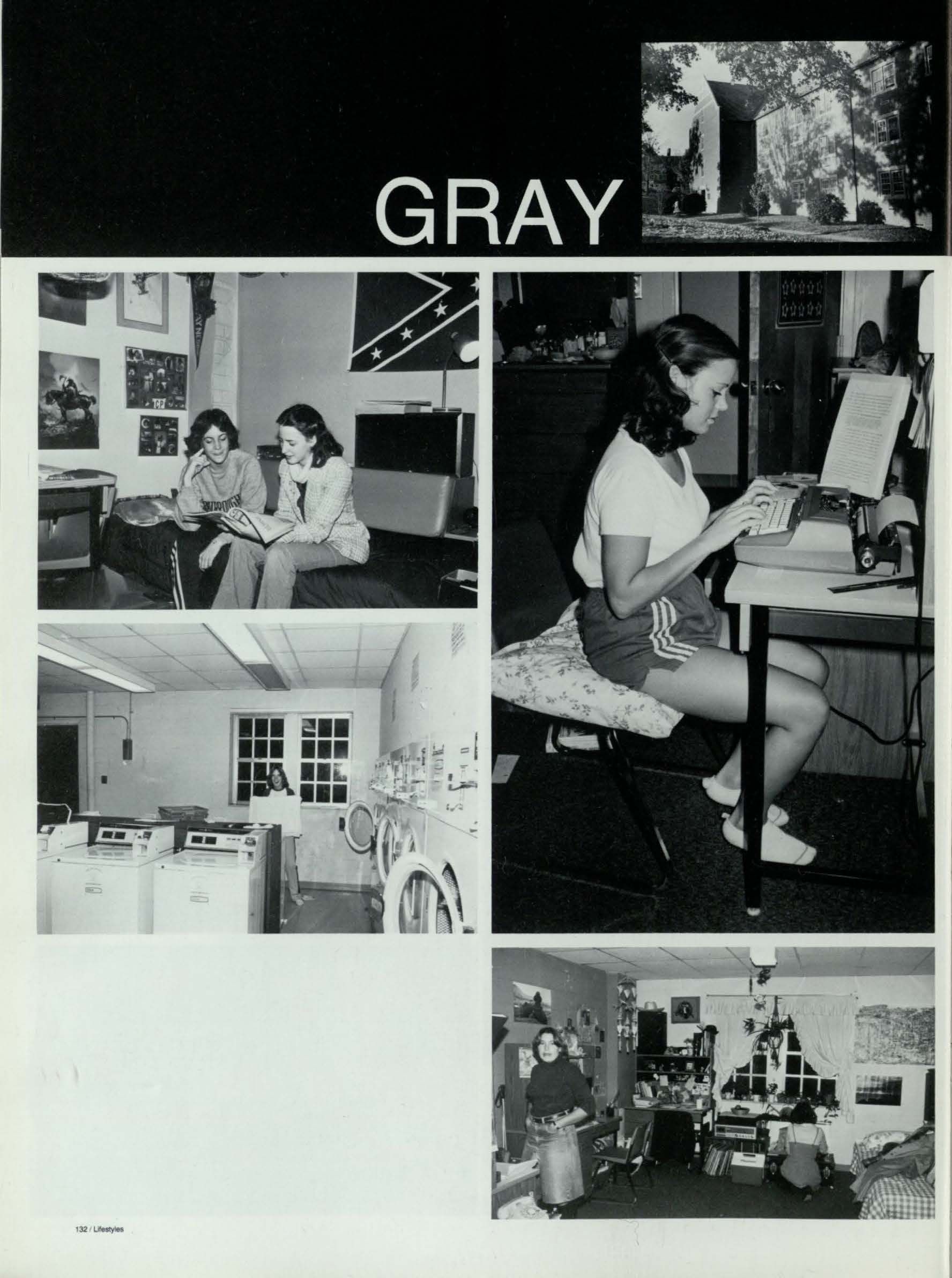

Researching the documents held in the University’s archive reaffirms that many things on this campus have stayed the same. What’s shown in these yearbooks, these photos, and these Collegian articles is so physically close to where I sit today. I’ve found myself wondering if the pictured room in Gray Court is the same one I lived in last year. I’ve looked up while I’m in the Tyler Haynes Commons to get the same vantage point captured in a certain shot. This spatial inseparability makes it all the more painful that the Gray dorm room in the picture has a Confederate flag on the wall, or that my view of the Commons is nearly identical, except for a banner for the gender-norm obsessed Women’s Lifestyle Committee. Just how far am I from the inequity enforced in these photos?

Researching the documents held in the University’s archive reaffirms that many things on this campus have stayed the same. What’s shown in these yearbooks, these photos, and these Collegian articles is so physically close to where I sit today. I’ve found myself wondering if the pictured room in Gray Court is the same one I lived in last year. I’ve looked up while I’m in the Tyler Haynes Commons to get the same vantage point captured in a certain shot. This spatial inseparability makes it all the more painful that the Gray dorm room in the picture has a Confederate flag on the wall, or that my view of the Commons is nearly identical, except for a banner for the gender-norm obsessed Women’s Lifestyle Committee. Just how far am I from the inequity enforced in these photos?

In seeking out my own student organizations on the Race & Racism project’s site, I acted on a different kind of immediacy. These are organizations I’m trying to make inclusive and aware spaces today. What lies in their pasts? Searching the name of the school’s literary magazine, The Messenger, gave me an answer.

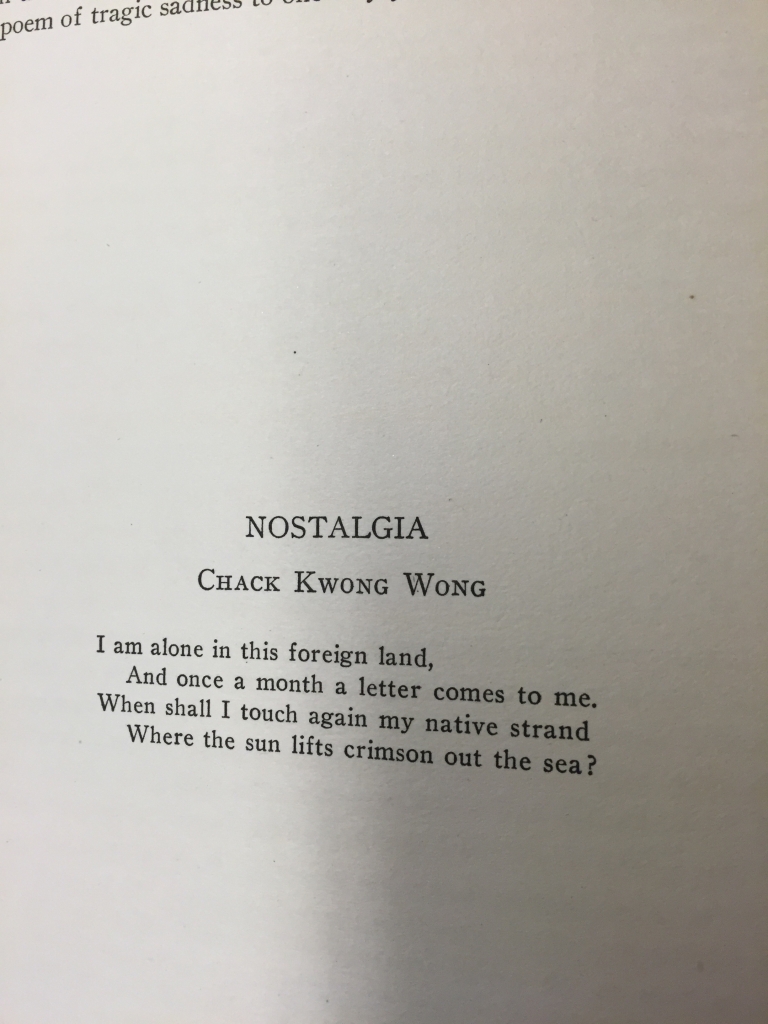

I’ve been very happy with the Messenger’s content during my run as a design editor. While reading works such as “A Korean American Dream” and “A Letter to Good Hair,” both featured in the Spring 2018 issue, I’ve seen the literary magazine serve as a welcoming place for minority student expression. The magazine hasn’t always been like this. While I found pieces from students of color dated as early as 1925, I also found many works rife with racial prejudice or outright racism; most were from the 1910s, and the latest was from 1931. A number of these stories and poems use slurs and/or play off of racial stereotypes. A 1915/16 short story titled “Methuselah Jones,” for example, characterizes the titular black man as superstitious and uneducated while referring to him using derogatory terms, and a 1924 short story called “Cross-Word Puzzle-itus” features a Chinese character named “Chu-Chin Chow” and pokes fun at aspects of Chinese culture such as the game mahjong. Chinese students were writing for the Messenger around the same time as this story’s publication. As mentioned, Chinese student Chack Kwong Wong’s “Nostalgia” was featured in the magazine in 1925. The poem lends this post its title and deals with Wong’s homesickness “in this foreign land.” In 1927, the Messenger contained “When Nothing Is Left,” “First Love,” and “Crossing” by Poon Kant Mok, a Chinese student who also explored themes of homesickness, along with those of love and memory. But the Messenger certainly wasn’t a welcoming space for these students to express themselves and their anxieties, as it published pieces that mocked their culture before and after their involvement with the magazine. In 1929, for example, a review of the play “The Silent House” uses a racial slur to describe a Chinese character. The use of this derogatory term exhibits a blatant lack of respect for Chinese students at Richmond and their contributions to campus culture, of which the Messenger is but one facet. Yes, students such as Chack Kwong Wong and Poon Kant Mok were allowed to contribute, but their participation was alongside works that attempted to dismantle their depth and self-determination as minority students. The presence of these discriminatory works tells a lot about how white students on campus felt about and treated their Chinese peers.

I’ve been very happy with the Messenger’s content during my run as a design editor. While reading works such as “A Korean American Dream” and “A Letter to Good Hair,” both featured in the Spring 2018 issue, I’ve seen the literary magazine serve as a welcoming place for minority student expression. The magazine hasn’t always been like this. While I found pieces from students of color dated as early as 1925, I also found many works rife with racial prejudice or outright racism; most were from the 1910s, and the latest was from 1931. A number of these stories and poems use slurs and/or play off of racial stereotypes. A 1915/16 short story titled “Methuselah Jones,” for example, characterizes the titular black man as superstitious and uneducated while referring to him using derogatory terms, and a 1924 short story called “Cross-Word Puzzle-itus” features a Chinese character named “Chu-Chin Chow” and pokes fun at aspects of Chinese culture such as the game mahjong. Chinese students were writing for the Messenger around the same time as this story’s publication. As mentioned, Chinese student Chack Kwong Wong’s “Nostalgia” was featured in the magazine in 1925. The poem lends this post its title and deals with Wong’s homesickness “in this foreign land.” In 1927, the Messenger contained “When Nothing Is Left,” “First Love,” and “Crossing” by Poon Kant Mok, a Chinese student who also explored themes of homesickness, along with those of love and memory. But the Messenger certainly wasn’t a welcoming space for these students to express themselves and their anxieties, as it published pieces that mocked their culture before and after their involvement with the magazine. In 1929, for example, a review of the play “The Silent House” uses a racial slur to describe a Chinese character. The use of this derogatory term exhibits a blatant lack of respect for Chinese students at Richmond and their contributions to campus culture, of which the Messenger is but one facet. Yes, students such as Chack Kwong Wong and Poon Kant Mok were allowed to contribute, but their participation was alongside works that attempted to dismantle their depth and self-determination as minority students. The presence of these discriminatory works tells a lot about how white students on campus felt about and treated their Chinese peers.

Discovering that a student publication that I’ve viewed as a safe haven for minority student expression accepted racist pieces was discomforting. It also made me wonder about minority student involvement with the magazine, and when exactly the culture of the Messenger shifted. The last explicitly racist piece I could find was from 1933; was this really the last one? Also, how much representation have minority students had in the magazine over the course of its history?

Like I mentioned, many things on this campus have stayed the same. I pass many of the buildings I see in these old photos daily, and there’s clearly still further for the University to go when it comes to inclusivity. I want to know where the literary magazine has stood in making this campus a more welcoming space. I’m not expecting any clear answers, but even if these initial questions don’t result in much, hopefully I can at least find more pieces from minority students over the years. The words of these students, past and present, need to be read and appreciated.