by Kristi Mukk

Kristi Mukk is a rising senior from Mililani, Hawaii. She is majoring in Rhetoric and Communications and minoring in English. She is a dancer and communications director for Ngoma African Dance Company. This is her first time working for the Race & Racism Project as a Summer Fellow, and she is excited to continue her work in the course Digital Memory & the Archive in Fall 2018.

The following blog post contains some contentious language. Please consider the intent of its use as you read on.

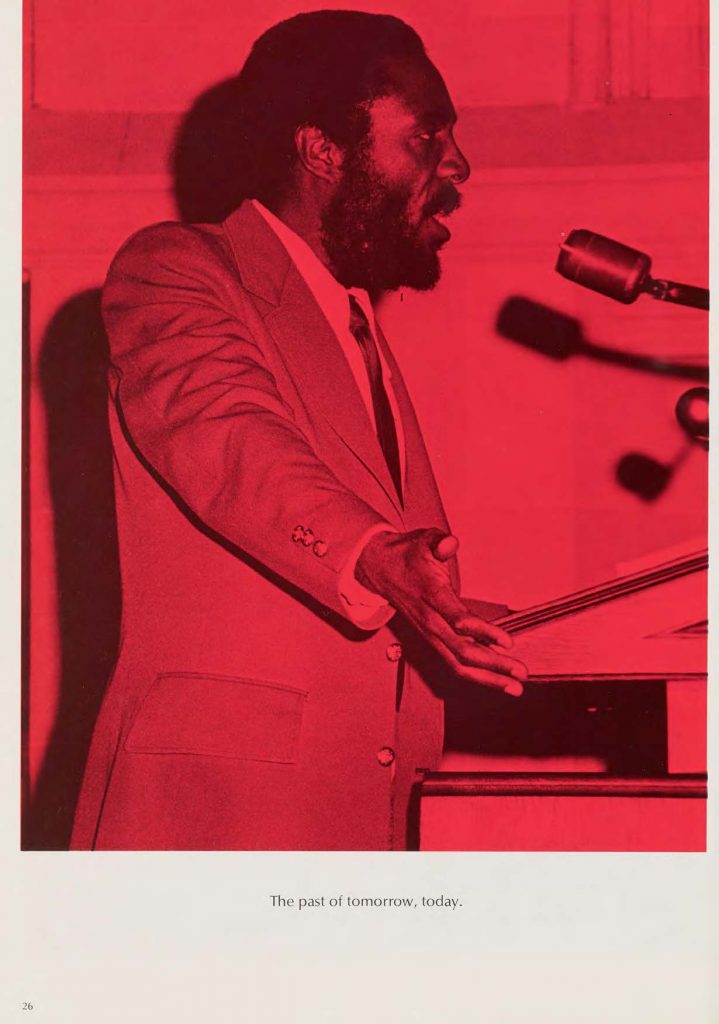

Archival work sometimes requires you to act like a detective by following a series of artifacts and connecting all the dots in order to uncover a story. My first archival detective journey started with a full-page photo of a black man I found in The Web 1971 yearbook. During this time, it was quite rare to find minorities represented in the yearbooks, let alone have a dedicated full-page photograph. The speaker’s name was not mentioned in the caption of the photo, so I emailed our Project Archivist, Irina Rogova, to see if she could identify the man. She informed me that he was Dick Gregory, a black comedian, author, actor, activist, and civil rights leader who came to speak on campus in December 1970 as part of a lecture series. This sparked my interest, so I decided to look through the Collegian newspaper archives to find more background and context.

Archival work sometimes requires you to act like a detective by following a series of artifacts and connecting all the dots in order to uncover a story. My first archival detective journey started with a full-page photo of a black man I found in The Web 1971 yearbook. During this time, it was quite rare to find minorities represented in the yearbooks, let alone have a dedicated full-page photograph. The speaker’s name was not mentioned in the caption of the photo, so I emailed our Project Archivist, Irina Rogova, to see if she could identify the man. She informed me that he was Dick Gregory, a black comedian, author, actor, activist, and civil rights leader who came to speak on campus in December 1970 as part of a lecture series. This sparked my interest, so I decided to look through the Collegian newspaper archives to find more background and context.

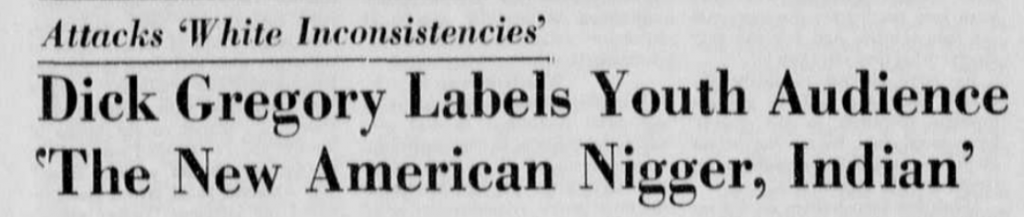

In the Collegian archives, I discovered an article that summarizes the main points of Gregory’s lecture. The article states that his lecture was attended by a crowd of about 800, mainly consisting of students. Gregory states that the duty of young people is to “get blamed for everything” as they are the “new American n—–” and “Indian,” however, the young people are key to solving “this country’s problems.” Gregory goes on to elaborate that minorities are scapegoats that are blamed for all of the country’s problems. He points out racism in the United States as “beautiful people” such as Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and Malcolm X are being wiped out while others are ignored by the police. He states that this racism has trickled down to the black youth. He gives an example of a five-year-old black boy who, when asked to draw himself, draws a picture of an animal—Gregory views this is a result of black people being stereotyped as wrongdoers, while those in policy-making positions are white. He argues that black people in America are “reacting to your racism.”

I also found another article from the Collegian entitled “Alienation” that describes the controversy that Gregory’s speech generated among alumni who sent letters to President George Modlin addressing their concerns or stating their intention to withhold their financial donations. The unnamed author of the article criticizes the speaker selection committee as they “chose an unbalanced slate of speakers” because Dick Gregory and the lecturers “are highly critical of current America.” The author asserts that this monopolizes free speech as the speakers are all critics and are not representative of a variety of viewpoints. The next clue that I found in this article was that it mentioned the alumni letters concerning Gregory’s lecture being read to President Modlin at the President’s Advisory Council meeting on March 8, 1971. I then decided to go to the University Archives in search of these letters.

In the folder containing notes from the President’s Advisory Council meeting, I discovered three letters addressed to President Modlin from unnamed alumni regarding Gregory’s lecture. The names of these alums appears to have been cut off the letters, but it is uncertain whether this happened before or after they went into the archive. A letter from one unnamed alum states their intentions to “revise my will” after reading the list of speakers that will be lecturing on campus as they now “would not like for one penny of my money to be used to sponsor people listed to speak.” Other speakers in this lecture series included: Stewart Udall, former Secretary of the Interior and an avid conservationist; Joseph Sorrentino, a lawyer and ex-convict specializing in prison reform; Brit Hume, an investigative reporter; and James Kilpatrick, a newspaper columnist and supporter of Massive Resistance to the Brown v. Board of Education decision.

In the folder containing notes from the President’s Advisory Council meeting, I discovered three letters addressed to President Modlin from unnamed alumni regarding Gregory’s lecture. The names of these alums appears to have been cut off the letters, but it is uncertain whether this happened before or after they went into the archive. A letter from one unnamed alum states their intentions to “revise my will” after reading the list of speakers that will be lecturing on campus as they now “would not like for one penny of my money to be used to sponsor people listed to speak.” Other speakers in this lecture series included: Stewart Udall, former Secretary of the Interior and an avid conservationist; Joseph Sorrentino, a lawyer and ex-convict specializing in prison reform; Brit Hume, an investigative reporter; and James Kilpatrick, a newspaper columnist and supporter of Massive Resistance to the Brown v. Board of Education decision.

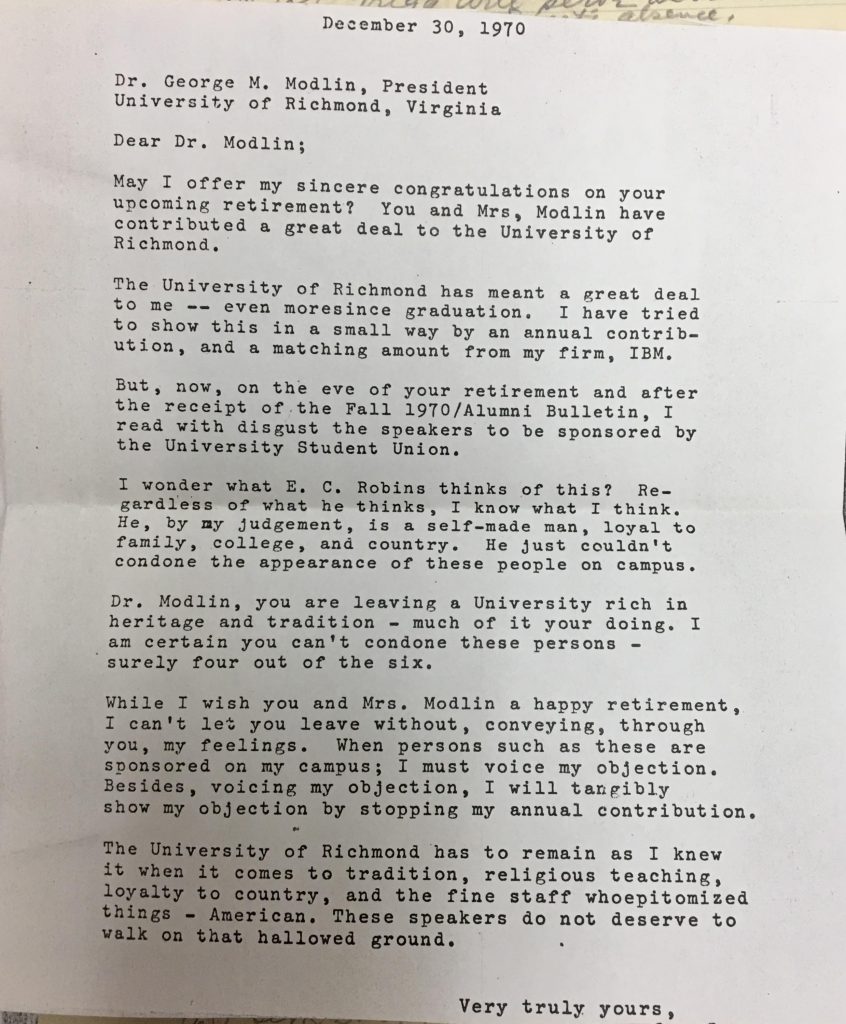

A letter from another unnamed alum expresses “disgust” at the list of speakers sponsored by the University Student Union and states that E. C. Robins “couldn’t condone the appearance of these people on campus.” In 1969, Robins gifted $50 million to the University, giving the University independent financial security. The alum asserts that their objection to these speakers will be tangibly shown through “stopping my annual contribution” as they believe that “these speakers do not deserve to walk on that hallowed ground.” This alum expresses their desire for the University of Richmond to remain rooted in “tradition, religious teaching, loyalty to country…American.” In the third letter, an alum states that they are “shocked beyond my ability to express my displeasure that the University would permit Dick Gregory to grace the podium.” The alum explains that they have been a “consistent contributor” to the Alumni fund, but they will now discontinue their annual gift and have the money allocated in their will to the University revoked. The alum asserts that “academic freedom is to be recognized,” but that “people like Gregory want to disrupt the establishment.” Although these alumni decided to withhold their financial donations, President Modlin defended the principle of free speech as essential to the University. In spite of all this controversy, Dick Gregory came back to speak on campus in 1973 as part of another lecture series on campus.

The coded language used by these alumni when using words such as “tradition,” “loyalty to country,” and “American” and describing these speakers as “disruptive” and worthy of “disgust” avoid blatantly stating that a pro-black, anti-racist speaker at a predominantly white institution is not wanted. This controversy brings to mind the modern day conversation surrounding free speech on campus and who is invited to speak and who is not. President Crutcher’s article “Defending the ‘right to be here’ on campus” argues that those who hold politically conservative viewpoints should not be silenced and describes how Karl Rove’s lecture as part of the Sharp Viewpoint Speaker series at UR was an example of civil discussion. In response to President Crutcher’s article, UR professor Dr. Eric Grollman argues that the free speech of people who “undermine the humanity and safety of marginalized groups” should not be protected. He goes on to assert that free speech has been weaponized by the right and results in the silencing of people of color and those who speak out against racism. So should freedom of speech still be protected for people like conservative lecturer James Kilpatrick in 1973 who was a supporter of Massive Resistance? Should free speech be protected if it endangers the safety of others or challenges their humanity?