by Catherine Franceski

Catherine Franceski is rising junior from Washington, D.C. majoring in Philosophy, Politics, Economics & Law (PPEL) with concentration in politics and minoring in Rhetoric & Communication Studies. She is the president of Phi Alpha Delta pre-law fraternity, and a member of the Westhampton College Honor Council. This is her second year working on the Race & Racism Project. Last summer, she focused on studying the lives and legacies of “hidden” black figures in Richmond, Virginia’s history.

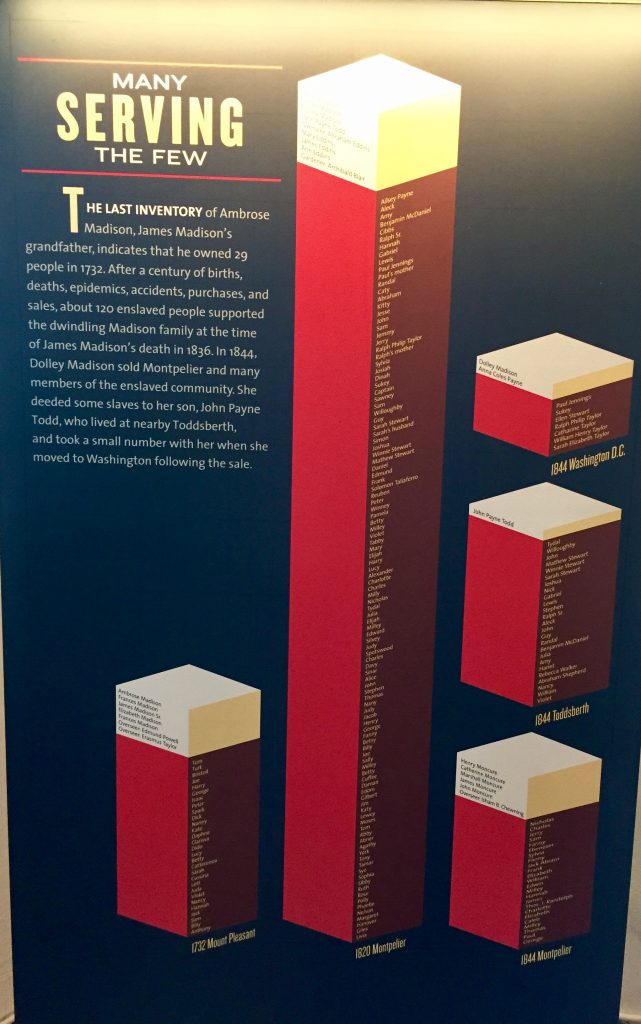

Montpelier is the estate and plantation home of James and Dolley Madison. It is where James Madison, the fourth president of the United States, penned several invaluable documents in America’s history, such as the Virginia Plan, which would provide the groundwork for the U.S. Constitution, and the Federalist Papers. Furthermore, it was also home to a population of more than 100 enslaved persons who waited upon the Madisons and their visitors, maintained the mansion, and labored in the fields.

Looking off the stately front porch of Montpelier, one is struck by the awesome Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia. While the splendor of the location, mansion, and gardens is striking, a relatively new exhibit, called “The Mere Distinction of Colour,” addresses a darker side of Montpelier– enslavement. The exhibit describes and pays tribute to the enslaved persons on the plantation. It also places Montpelier in the larger context of enslavement in the United States, and explains enslavement’s role in shaping America, from its historical economy to its hidden influences on the Constitution. Finally, “The Mere Distinction of Colour” links the legacy of enslavement the present-time through multimedia featuring such topics as racism and police brutality in America.

Looking off the stately front porch of Montpelier, one is struck by the awesome Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia. While the splendor of the location, mansion, and gardens is striking, a relatively new exhibit, called “The Mere Distinction of Colour,” addresses a darker side of Montpelier– enslavement. The exhibit describes and pays tribute to the enslaved persons on the plantation. It also places Montpelier in the larger context of enslavement in the United States, and explains enslavement’s role in shaping America, from its historical economy to its hidden influences on the Constitution. Finally, “The Mere Distinction of Colour” links the legacy of enslavement the present-time through multimedia featuring such topics as racism and police brutality in America.

Kristi Mukk, another member of Team Archive and A&S Summer Fellow, and I met with the the Senior Research Archaeologist at Montpelier, Mr. Terry Brock. He shared with us the importance to his work of involving the descendant community of the enslaved persons at Montpelier. In one example, he explained how he and his team had found a pipe with a Masonic symbol on it during an excavation. He and a fellow archaeologist immediately thought that it was possible confirmation of what many people suspected– that James Madison was a Freemason. The members of the descendant community, however, derailed that idea. They explained that their ancestors would have also used the Freemason symbols, as they too subscribed to the Freemason ideals of brotherhood, and independence, and liberty, among others. Moreover, upon further inspection, the researchers found out that the pipe had undergone a makeshift repair involving clay and reed on the bottom. If the pipe had belonged to James Madison, he most likely would have gotten a new pipe if his old one broke. This meant that is likely belonged to an enslaved person. The pipe was one example of how engaging the descendant community and hearing their voices added accuracy and nuance to the historical narrative.

Kristi Mukk, another member of Team Archive and A&S Summer Fellow, and I met with the the Senior Research Archaeologist at Montpelier, Mr. Terry Brock. He shared with us the importance to his work of involving the descendant community of the enslaved persons at Montpelier. In one example, he explained how he and his team had found a pipe with a Masonic symbol on it during an excavation. He and a fellow archaeologist immediately thought that it was possible confirmation of what many people suspected– that James Madison was a Freemason. The members of the descendant community, however, derailed that idea. They explained that their ancestors would have also used the Freemason symbols, as they too subscribed to the Freemason ideals of brotherhood, and independence, and liberty, among others. Moreover, upon further inspection, the researchers found out that the pipe had undergone a makeshift repair involving clay and reed on the bottom. If the pipe had belonged to James Madison, he most likely would have gotten a new pipe if his old one broke. This meant that is likely belonged to an enslaved person. The pipe was one example of how engaging the descendant community and hearing their voices added accuracy and nuance to the historical narrative.

Overall, the exhibit was teeming with descendant voices as well as stories of self-determination and resistance of the enslaved persons that lived there. Another artifact that Terry highlighted was a second pipe that had the word “Liberty” and a picture of Lady Liberty on it which had been found in one of the cabins of the enslaved people. I imagined an enslaved person smoking out of the pipe, an act of subtle resistance.

There were also stories of less subtle resistance. An animated film told the story of Ellen Stewart, an enslaved woman at Montpelier whose family underwent multiple separations as members were sold away to other plantations. Ellen was also part of the “seventy-seven slaves who attempted to escape bondage aboard the schooner Pearl out of Washington,” which ultimately failed. She was returned to Dolley Madison, and put up for sale. She finally achieved her long-desired freedom when abolitionists bought her out of bondage.

There were also stories of less subtle resistance. An animated film told the story of Ellen Stewart, an enslaved woman at Montpelier whose family underwent multiple separations as members were sold away to other plantations. Ellen was also part of the “seventy-seven slaves who attempted to escape bondage aboard the schooner Pearl out of Washington,” which ultimately failed. She was returned to Dolley Madison, and put up for sale. She finally achieved her long-desired freedom when abolitionists bought her out of bondage.

Through telling of these stories and engaging the descendant community, Montpelier acknowledges its legacy as home of a paramount figure in American history, while also crediting the people who spent their entire lives working his home and the physical space that the visitors walk upon. Montpelier broke with the stereotypical narrative portrayed at many plantation homes by holding the histories of the enslaved persons on the same level as the Madisons. In doing so, it managed to honor the enslaved persons and their stories that have not been told before. Although the exhibit tells a sad story of human exploitation and dehumanization, the attention and power it confers to the enslaved people and their ancestors can be seen as a motion in the right direction for racial equality and respect.