On March 16, 2018, five undergraduate students who have worked with the Race & Racism at the University of Richmond Project had the opportunity to present at the Lemon Project Symposium at the College of William and Mary. The panel, entitled “Seeing the Unseen and Telling the Untold: Institutions, Individuals, and Desegregating the University of Richmond,” was moderated by Dr. Nicole Maurantonio and featured Dominique Harrington, Madeleine Jordan-Lord, Elizabeth Mejía-Ricart, Jennifer Munnings, & Destiny Riley. Below you will find the text and slide images of Madeleine Jordan-Lord’s presentation, focusing on the research she conducted while taking “Digital Memory & the Archive in the fall of 2016.” Click here to explore the exhibit she and her teammates created, “George Modlin’s Segregated University of Richmond.”

On March 16, 2018, five undergraduate students who have worked with the Race & Racism at the University of Richmond Project had the opportunity to present at the Lemon Project Symposium at the College of William and Mary. The panel, entitled “Seeing the Unseen and Telling the Untold: Institutions, Individuals, and Desegregating the University of Richmond,” was moderated by Dr. Nicole Maurantonio and featured Dominique Harrington, Madeleine Jordan-Lord, Elizabeth Mejía-Ricart, Jennifer Munnings, & Destiny Riley. Below you will find the text and slide images of Madeleine Jordan-Lord’s presentation, focusing on the research she conducted while taking “Digital Memory & the Archive in the fall of 2016.” Click here to explore the exhibit she and her teammates created, “George Modlin’s Segregated University of Richmond.”

Madeleine Jordan-Lord is a 2018 gradaute who majored in American Studies and History at the University of Richmond. She has worked on digital history projects, including the Race & Racism at the University of Richmond Project, as well as the Abbitt Papers special collection at Boatwright Memorial Library. Over the course of her time at UR, Madeleine has held internships at several non-profits–Art180, Virginia Historical Society, and Tricycle Gardens–creating public curriculum and education-based workshops.

Thanks, Dr. Maurantonio. Hello, I’m Madeleine Jordan-Lord and today I will be presenting a project I created in the Fall of 2016 with my classmates Dominique Harrington and Bailey Duplessie titled “George Modlin’s University of Richmond.”

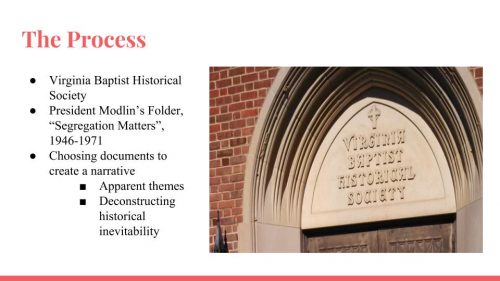

Our exhibit started from one folder, titled “Segregation Matters” from George Modlin’s presidential archive. The title of the folder is somewhat ambiguous, and what we found within it was a story of the continuous, tentious correspondence about segregation with the University’s president and his constituents leading up to the eventual integration of our main campus in 1968. The official story of integration that is typically told on our campus starts the narrative of Barry Greene, the first black residential Richmond College student, but even in this one folder we see that narrative complicated. We took this collection of documents spanning from 1946 to 1971 and pulled out themes that challenged the air of historical inevitability surrounding the topic of the integration of UR.

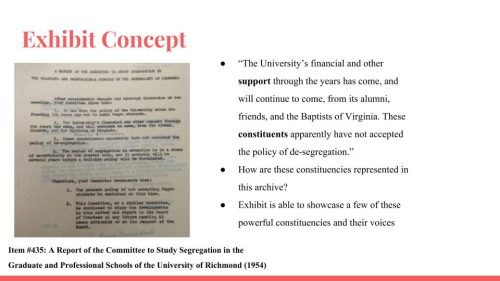

One document in particular, a Report of the Committee to Study Segregation in the Graduate and Professional Schools of the University of Richmond from 1954, became the grounding point for our exhibit. In this report, the Committee to Study Segregation named “constituents,” like alumni, friends, and the Baptists of Virginia, as UR’s support system. And they claimed that these constituencies did not accept the policy of desegregation. However, in reading through the documents in our folder, we saw that this wasn’t exactly the case. There were members of each of these constituencies speaking out against university segregation.

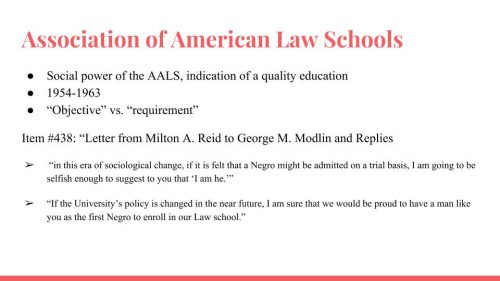

The first constituency we studied was the Association of American Law Schools. Within the “Segregation Matters” folder, we were able to piece together a small collection of correspondences regarding T. C. Williams School of Law at the University of Richmond, and the Association of American Law Schools that it belonged to. Being a member of this association carried a social power and legitimacy to the law program, and the AALS supported integration. In 1951, integration of all AALS schools was an objective and not a requirement, but the University would face negative repercussions if they failed to comply.

Still, UR remained segregated despite pressures from the AALS and from Dean Muse of the School of Law. George Modlin interacted directly with some black applicants to the law school, namely Milton A. Reid. Though it is not explicitly stated in the archival documents, Milton A. Reid was the founder of the Virginia chapter of the SCLC and worked alongside Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. for many years. Included in the above slide is an excerpt from Reid and Modlin’s correspondence.

In this, we see Modlin dismissing his responsibility and position of power, and also a passiveness towards integration. These letters indicate that there was interest in T.C. Williams School of Law by potential African American students, but that the University restricted them from attending.

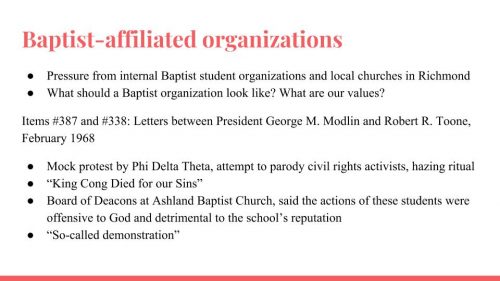

There was also pressure placed on George Modlin from Baptist organizations. This included internal pressures from groups like the Baptist Student Union, but also external pressures from Baptist Churches in the surrounding area. From the letters contained in the “Segregation Matters” folder, it is clear that many Baptist groups were struggling with the morality of segregation. They were asking questions like: “What should a Baptist organization look like?” and “What are our values?” Since the UR was a Baptist-affiliated school at the time, these questions of morality and image were relevant to the university as a whole.

One key moment took place in 1968, when the fraternity Phi Delta Theta required its pledges to participate in a public, racist hazing ritual. These white UR students put on a mock protest to parody civil rights activists and carried signs that read “King Cong Died for our Sins.” Though the university integrated this same year, this can hardly be called a welcoming environment for students of color.

This mock protest elicited a response from Robert R. Toone, who was on the board of deacons at Ashland Baptist Church who called the demonstration detrimental to the school’s reputation and offensive to God. Modlin downplayed the seriousness of this event by calling it a “so-called demonstration” and by stating that the fraternity had already apologized.

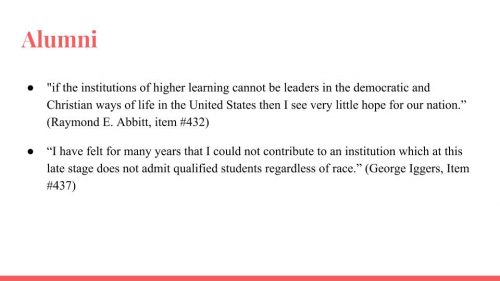

The final constituency group we studied was alumni voices. Though our scope was limited, we found documents in the “Segregation Matters” folder that indicated that many alumni did not agree with the University’s choice to remain segregated through most of the 1950s and 60s. These quotes above from 1963 show that some alumni, when asked to donate to the University, declined because of the issue of segregation. This contrasts directly from the report that frames this exhibit, and shows that some support–both social and financial–was withheld because of UR’s failure to integrate until 1968.

Our exhibit is framed to tell a story–one that gives texture to the narrative of desegregation at our University and that gives agency to those in these valued constituencies that pressured the university to change. A challenge we have in telling this story, is that it remains incomplete. This folder is in a way already curated, and does not capture the voices who were pro-segregation and likely in the majority during this time period. What our exhibit does do, however, is complicate the official narrative. Through these documents we are able to see the progression of social forces that lead to the eventual integration of our campus, and the story definitely did not start in 1968.

Thank you.