by Destiny Riley

Destiny Riley is a junior from Maumelle, Arkansas, majoring in Rhetoric & Communication Studies and double minoring in Sociology and American Studies. The most interesting part of this project for her was making connections between the ways that the University viewed race in the early to mid-20th century and how the University views race in the modern day. Destiny first contributed to the Race & Racism at UR Project during an independent study course in the Spring of 2017. This post was written as a part of Digital Memory & the Archive, a course offered in Fall 2017.

In 1965, Betty Jean Seymour, the director of religious activities for Westhampton College, conducted a study of Richmond and surrounding areas. She concluded that many Black, high-school age students in the area had low skills or were illiterate. Some had even forgotten basic skills such as how to hold a pencil for writing. This was because for a long time, specifically during the years of 1959-1964, Black students did not have the same access to privately-funded schools as white students. As I studied this article from the Collegian, I wanted to know more about why Black, high-school age students were so behind in skills and education during this time. Aside from the obvious segregation of public schools up until the 1950s, I felt as if there had to be more of a reason for this gap of education levels between Black and white students. As I delved deeper into the racial climate of this time, the blatant cause of this gap became very clear.

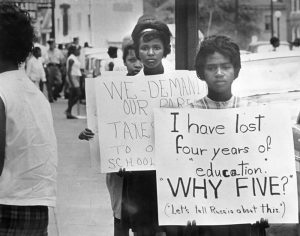

In 1954, the Supreme Court declared that state laws establishing separate public schools for Black and white students to be unconstitutional in the case of Brown v. Board of Education. In the state of Virginia, rather than integrating the public schools, numerous counties decided to close their public schools to combat this push for integration. This response by various counties in Virginia was known as Massive Resistance. Coined by Virginia State Senator Harry F. Byrd, Massive Resistance was a group of laws, passed in 1956, which were intended to prevent integration of the schools. I have heard and seen the term “Massive Resistance” numerous times during my time at this University. However, while doing more research into the term, it became clear that I did not know the immense impact it had on Black students. With this group of laws, state funds to public schools were cut off and public schools that attempted to integrate were closed in 1958. While the rest of the Virginia counties re-opened their public schools a few months after their closings, Prince Edward County did not follow suit. This county did not close its public schools until 1959, after many counties had re-opened their schools, and kept its schools closed for five years rather five months as other counties had. While Prince Edward County opened numerous private schools to educate the white children, no efforts were made by the county to educate the Black children. The private schools were supported by grants from the state and tax credits from the county. Prince Edward Academy, now known as the Fuqua School in Farmville, VA, became the “prototype for all-white private schools formed to protest school integration” (Virginia Historical Society). Meanwhile, Black students had to receive bare minimum education at makeshift schools in church basements or had to resort to living with relatives in nearby communities in order to attend their schools. Finally, in 1964, the U.S. Supreme Court deemed Virginia’s tuition grants to private schools unconstitutional, thus forcing Prince Edward County to reopen and integrate its schools.

Though the issue of Massive Resistance existed in the late 1950s and early 1960s, how much has really changed from then to now?

At this University, I am a part of a mentoring program in which we mentor students from John Marshall High School, which is a part of the collective known as Richmond City Public Schools. Richmond Public Schools are made up of over 75% African American students, with the majority of them receiving free or reduced lunch due to the high poverty rates in their families. White students make up only nine percent of the schools, with most white students attending to private schools or public schools outside of the county. Only 40% of the schools are accredited, with less than 60% of the students being proficient in skills such as reading, mathematics, and science (Virginia Department of Education). Many of these schools are known as the worst schools in the state, with low test scores, high crime area rates, raggedy buildings, and low graduation rates. In my opinion, there is no coincidence that the “worst schools in Richmond” are attended by poor, African-American students. As these schools have been in extreme need of help for decades, it makes one wonder: what is the state doing about this? While white students are receiving top notch educations, poor, Black students are left to struggle to compete with white students who are receiving better educations in better environments.

As you can see, the issue of race in regard to access to quality education has not changed dramatically since Massive Resistance in the 1950s and 1960s. This existing lack of access to quality education heavily suggests that Massive Resistance still exists, though it is being perpetuated in a different way than it previously was. In the Collegian article I previously mentioned, Betty Jean Seymour, the director of religious activities for Westhampton College, was advocating to numerous organizations on behalf of the Black children that were being denied education because of their race. She appealed to religious and nonreligious organizations as well as students, all at the University of Richmond, in hopes that they would donate to fixing this issue in Prince Edwards County. She hoped that they would donate enough money so that Black children could have access to better education in the county. This made me wonder, who is advocating for the Black children in need of better schools and better education today? Other than some people working in the schools and in the districts, it seems as if nobody cares enough about these students enough to enact change. If we want to truly say we have made progress since the days of Massive Resistance, it is essential that we provide them with better schools, education, resources, and opportunities. These students represent the future and deserve so much better than what they are receiving. Until this issue is resolved, or at least made better, any claim of progress from Massive Resistance is false.