by Dominique Harrington

Before beginning my fellowship, I sat down and researched sites of black history in Indianapolis in order to prepare for the community engagement aspect of the project. However, despite the size and rich history of the city, I only found three sites: The Bethel African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church, Crispus Attucks High School, and Indiana Avenue & The Madame C.J. Walker Theater (I will be visiting each of them over the duration of this summer).

This embarrassing list doesn’t even come close to encapsulating the impact that black folks have had on this city. What’s more is that this list continues to get shorter and shorter. The Bethel AME Church, the first black church in Indianapolis, was actually sold this past year and will be converted into a hotel. Crispus Attucks High School, Indiana’s first all-black high school, is currently being evaluated by the leaders of the Indianapolis Public School system to determine whether or not the school will remain open. The black history of the city is under attack, therefore, it’s my privilege to try and bring that which has been pushed out into the shadows, back into the spotlight.

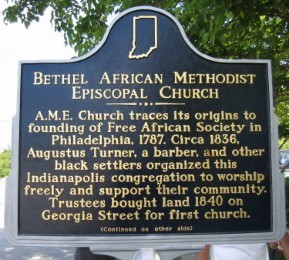

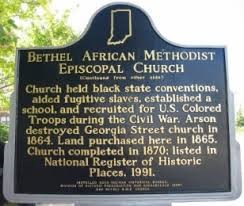

The Bethel AME Church of Indianapolis was built in 1869, cementing it as the oldest black church in the city. Since then, it served as both a religious sanctuary and a sanctuary from the rest of the city, considering the fact that black folks only made up three percent of the city in the mid-nineteenth century. To illustrate its significance, in the 1920’s, when Indiana’s Democrats were trying to get the black vote, they came to Bethel AME Church to speak

Even though Bethel AME Church is closed, I began there because it was built first. So, I got in my car and plugged the address, 414 West Vermont Street, into Google Maps at about 1 o’clock, as to avoid downtown traffic. Although I live about a 15-20 minute drive from downtown, I’m familiar with the how to navigate the area. However, I initially had difficulty finding the church. I am familiar with Military Park, which is across the street (and where the LGBTQ+ Pride Festival took place this year). I’m also familiar with the Canal Street Apartments because I’m familiar with the Indiana Canal, a destination for many to walk around on a nice summer day. Therefore, when I was told to make a right into what seemed like more parking for these apartments, I figured that I had input the wrong address. I had the correct address, this landmark is simply tucked in a corner, with high end apartments and Indiana University Purdue University Indianapolis (IUPUI) buildings flanking it on all sides. As I pulled into the cul de sac where the church rests, the first thing I saw was this sign, letters chipped, and a “welcome” meant for a time and a people that are long gone.

Beyond the signage, the church has been certainly abandoned, with boarded up walls and paper covering its windows.

As I left the site, I noticed that there was a historical landmark sign visible from the street. Although it is a start, a sign can’t encapsulate this site; this one certainly doesn’t. This sign doesn’t talk about all the church did to help black folks arriving to the city as part of the Great Migration, or how it was the hub for social justice and political organizing, or how the Indianapolis chapter of the NAACP was founded there, or even how this was the space where black folks could congregate for social and cultural events. This historic landmark of a church has been forgotten. Because it is tucked away, overshadowed by apartments and college buildings, no one is forced to remember.

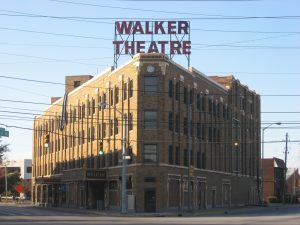

Memory is both visible and collective as we’ve grappled with through class discussions and course readings. One can derive value through architecture. Therefore, I can infer that the city has valued gentrifying black neighborhoods for the sake of high-end apartments and “revitalizing” the city’s downtown. However, revitalize for whom? This city’s black communities have been displaced and its black history continues to be erased. Memory is visible and collective, but it is also selective. The Madame CJ Walker Theater is essentially the last major black historical landmark in downtown Indianapolis. Therefore, the city has chosen whose history is worth remembering and whose isn’t. This project has taught me that it’s incumbent upon us all to interrogate when, why, and how, collective memories fail. Who do they fail? Why did they fail them? But most importantly, how do we change the narrative so we don’t forget those that were meant to be forgotten?

For more information on Indiana’s black history, visit some of the Indiana Historical Society’s digital collections. Also learn more information on historic Indianapolis and Bethel AME Church.

Sources

Lewis, Olivia. “Bethel AME fights to keep legacy alive” Indianapolis Star, August 22, 2015.

Dominique “Dom” Harrington is a rising junior majoring in American Studies and minoring in Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies. She worked with the Race and Racism project for the Fall 2016 seminar, Digital Memory and the Archive. This summer, she is thrilled to continue working with this project remotely from her hometown of Indianapolis, Indiana.