Since its introduction in Disneyland in 1966, It’s a Small World After All has been one of the most well known rides with a catchy, and often annoying, theme song. From the first reindeer on a hilltop in Scandinavia to the final “Au revoir,” this lighthearted boat ride takes many children on their first global adventure in a unique way that, while bright, colorful, and lively, may not be so accurate.

Since its introduction in Disneyland in 1966, It’s a Small World After All has been one of the most well known rides with a catchy, and often annoying, theme song. From the first reindeer on a hilltop in Scandinavia to the final “Au revoir,” this lighthearted boat ride takes many children on their first global adventure in a unique way that, while bright, colorful, and lively, may not be so accurate.

Due to the space available and the implications that come with a children’s boat ride at a theme park, the journey takes place along a cartographically inaccurate route. The audience travels along an extensive, winding river that travels the “world” with the postcard-perfect pictures of various countries with mechanical dolls dancing and the prominent architecture and stereotypical clichés associated with that country appearing on either side. Disney focused on the prominent memorable features of each country and displayed what the audience would be familiar and happy with, instead of anything about the country or its culture. While these icons, such as the Taj Mahal in India or the pyramids in Egypt, are not inaccurate, they minimize the experience of the world to a few main symbols when, in reality, there is much more depth to each country through the culture, the food, and the daily lives of the people. This same approach was present in the route and layout of the world throughout the ride. However, Disney’s ideology is crucial because it provides the basis for the “geographical imagination,” or the cultural and geographical understanding, of the world for the majority of people who board this ride and may not have the opportunity to visit all of the countries around the world.

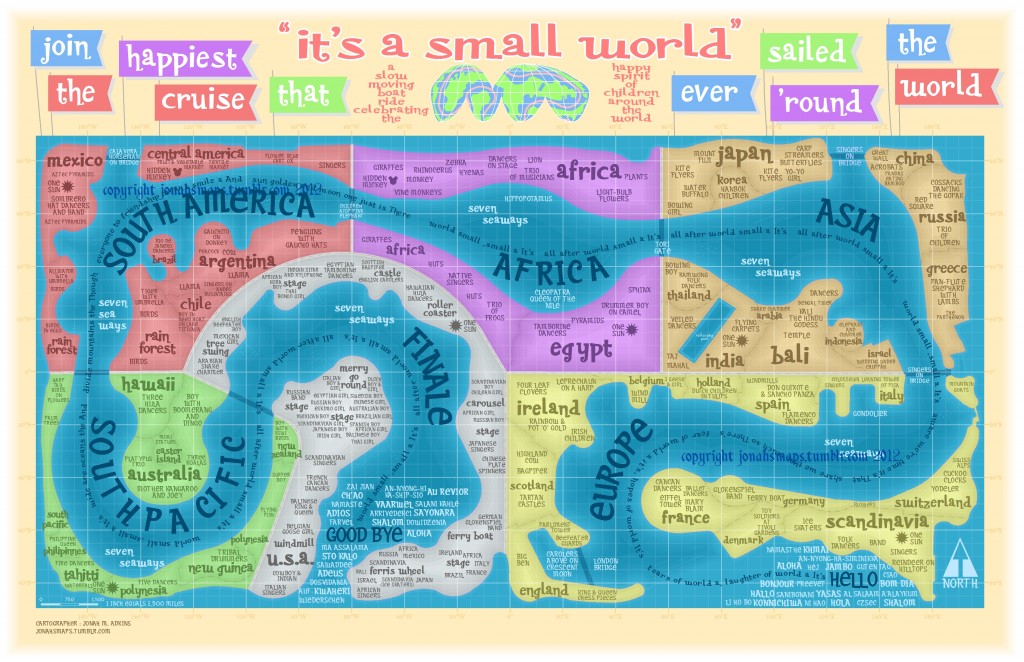

The map “It’s a Small World” by Jonah M. Adkins captures Disney’s ideological viewpoint perfectly. It displays the journey on a fun, colorful map of the route the boat takes around the world. On the map, the individual countries are labeled, but there are no lines or barriers to portray a distinct separation; instead, the countries all connect together in one continuous strip. While it makes sense that a ride appealing to children would present the world as a harmonious, fluid place, this portrayal conceals the reality of the world we live in where borders and wars over territory exist. Not only is there little distinction between countries on the map, but also the groups of countries that represent the assorted continents and regions flow into each other seamlessly, making it appear as if it really is just one small world after all.

The only tactic that does, however, separate these regions is the color-coding by the cartographer. The ride may link the entire world together into one, but the cartographic choice to color different regions different colors enables the audience to see the distinction between various areas around the world. It also gives the viewer a more concrete idea of the order the ride progresses through the world and which regions are put next to one another. This choice by the cartographer is a political one because he felt the need to distinguish between regions even though that distinction wasn’t present on the ride he is portraying. This grouping indicates some relationship or similarity between the countries included in each color, which is an inaccurate assumption that ignores the diversity present within each continent. Conversely, Disney chose not to specifically identify the various continents, even though it did conform to the idea of continents through the order the ride progresses.

The order itself is an interesting component brought out by the map that, while not a choice of the cartographer’s, reveals more about the identity and viewpoint of Disney. The world is travelled in a circular way, starting in Europe and proceeding to Asia, Africa, South America, and the South Pacific, and ending in North America. There is a unique contrast between the commencement in Europe, the origin of American colonization and the continent that shaped many of America’s core values, and the conclusion in North America, creating a feeling of returning “home” after a long journey around the world. These ideological decisions made by Disney show the origin of the ride and the company itself by making its familiar homeland the grand finale.

The other curiosity apparent from this map is Disney’s decision on the location and inclusion of certain countries. Holland is located next to Spain, Thailand is across the water from Japan, and Hawaii borders Australia. The image of one small world and the inclusion of visually appealing buildings and dancing machines take priority over global accuracy, which is a curious choice for a ride that introduces many young children to the entire world for the first time. Given that this may be their first “experience” with the world, Disney’s choices may influence the idealizations or stereotypes of its younger audience. Along with the inaccurate location of the countries, the choice to make the second-to-last region the South Pacific instead of the final continent of Australia again reveals the ideological nature of the map. The most efficient method would have been to organize the boat ride through the continents. Since, however, the continent of Australia only includes one country, it would have paled in comparison to the other continents, so the next-to-last section is the greater South Pacific area instead. Along with this breaking of the continent theme, certain countries are in questionable locations, such as the inclusion of Hawaii in the South Pacific instead of North America and the placement of Mexico next to Central America in the South American section of the map.

Overall, this map is an excellent portrayal of Disney’s It’s a Small World After All with its bright colors and journey through various countries on the fun boat ride around the world. However, the map highlights some ideological choices made by Disney that speak to Disney’s identity and the impression it leaves on naïve children. The themes and décor and the inclusion of stereotypes, along with the general flow of the ride, put the educational value of the ride at risk.

This map is a very interesting take on projecting a unique world view. Certainly this map would not be very successful in helping someone navigate across the world, but the childlike and simple aesthetic gives it a certain charm. In addition, the attractions that are placed along the map seem to try and describe the culture of the people that might populate the locations they lay in. This gives us a view on what the map creator might think would be important when describing the lives of different groups of peoples.

I loved your unique choice of map and intriguing analysis. The map isn’t a direct representation of reality, and thus makes some interesting choices into which you went into depth. Your idea of the map’s cultural simplifications point out the nationalistic, sometimes ignorant American perspective. Culture within the map is easily apparent in this case, and you’ve done a nice job in analyzing the creator’s intentions.

First of all, I love this choice of a map. It caught my attention immediately, after scrolling through mostly black and white or dull-colored maps. I really enjoyed your opening, which really drew me in because it reminded me of all the times I went to Disneyland as a child. It’s interesting that as catchy as this map looks, it is not an actual representation of reality, but that’s what makes it exciting. I like what you said about the colors and the cartographer using them as a way to distinguish between each country. I also like how you pointed out that the placement of each country must have bee deliberate by the cartographer–there’s a reason one country is placed next to another. It’s really interesting how, as you say, this map is “cartographically innacurate”, yet it is still a unique representation of how we really do live in a “small world after all”.