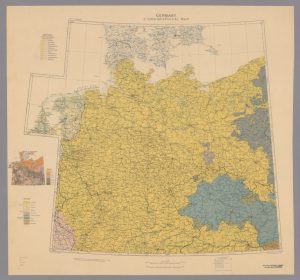

“Don’t judge a book by its cover” doesn’t just apply to books: a map that seems plainly informative at first glance can have many hidden implications. One such map is Germany: Ethnographical Map, produced in 1918 by the British War Office. It displays, as one might expect, the majority ethnic groups in Germany and the surrounding area. Importantly, the map was published prior to the end of World War I, as seen in Germany’s borders; it still includes Alsace-Lorraine (the area surrounding Strassburg in the southwest of Germany) and a significant amount of territory in what is today Poland. Some of the things that make this map particularly interesting include the choice to include the Netherlands yet not East Prussia and Germany’s Polish territory, its submap of population density, the extra information on the ethnic German population in Schleswig-Holstein (the German side of the Danish-German border region), and how the map in a sense predicts the British policy of appeasement and some of the key factors in the lead up to World War II some two decades later.

“Don’t judge a book by its cover” doesn’t just apply to books: a map that seems plainly informative at first glance can have many hidden implications. One such map is Germany: Ethnographical Map, produced in 1918 by the British War Office. It displays, as one might expect, the majority ethnic groups in Germany and the surrounding area. Importantly, the map was published prior to the end of World War I, as seen in Germany’s borders; it still includes Alsace-Lorraine (the area surrounding Strassburg in the southwest of Germany) and a significant amount of territory in what is today Poland. Some of the things that make this map particularly interesting include the choice to include the Netherlands yet not East Prussia and Germany’s Polish territory, its submap of population density, the extra information on the ethnic German population in Schleswig-Holstein (the German side of the Danish-German border region), and how the map in a sense predicts the British policy of appeasement and some of the key factors in the lead up to World War II some two decades later.

A good place to start when critiquing maps is what the cartographers choose to include and exclude from the map. The choice to include Germany in a map about Germany makes perfect sense of course, as does the inclusion of what was at the time the Austro-Hungarian Empire (the areas included in the map are today primarily part of the Czech Republic and Austria), given that the UK was at war with both countries. What is not immediately obvious is why the British chose to include the Netherlands, especially when we can clearly see that the map had to be expanded west somewhat awkwardly to include all the Dutch territory. Their reasoning for the decision to include the Netherlands might be their proximity to the British Isles, the fact that the Dutch are generally considered a Germanic people, and/or Germany’s control of the Netherlands for much of the war, but it’s not at all clear. We also can see also that they decided against including Germany’s eastern territory, and instead included it in an adjoining map on Poland. This clearly points to the idea that the British consider Poland to be its own separate region with its own history and culture; essentially they want Poland to have its own nation-state, which makes sense considering they were at war with Germany at the time this map was published and would rather prefer it if the Poles rose up against Germany to form their own country.

Beyond the central map, there are also a small map detailing the population density of Germany and a bar chart showing the makeup of some of the towns in Schleswig-Holstein. From the population density map, the main thing to take away is that northern Germany is much more sparsely populated than the south or the west. Outside of a few key cities like Hamburg and Berlin, there are only 25-50 people per square kilometer in the north, as compared to many areas of the south and west with 100-150. Outside of that information, the population map is relatively uninteresting, with the only interesting part being the choice to include it in the first place—the map seems to be included actually just to inform people. The information on Schleswig-Holstein is quite interesting, as on the map it is one of only two regions where the cartographers decided to indicate a mixture of ethnicities, with the other region being the borders of what is today the Czech Republic. The choice to include extra information on the Danish-German border over the German-Czech border places more emphasis on regions closer to the UK yet again. Long term of course, the German-Czech border turned out to be much more historically important.

Anyone who has taken a history course that at some point went over World War II probably recognizes the term Sudetenland, the border regions of the Czech Republic that prior to the end of WWII were inhabited almost entirely by ethnic Germans. This fact was of course used by Hitler as justification for invasion and annexation of this region, which was allowed by the major European powers in the Munich Conference led by British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain and his appeasement policy. In this map, published by the British two decades prior, we can already see exactly what Hitler used to justify his aggression and a part of why the British decided to pressure Czechoslovakia to concede the land to him. We can see a similar idea in the ethnography of Alsace-Lorraine, which in this map is shown as ethnically German. That region would then be given back to France (Germany had annexed it in its unification war against France in 1870) in the Treaty of Versailles, among many other punitive provisions which provided yet more fuel for German-French tensions. This ethnographic map of Germany which seems relatively simple at first glance, just providing the ethnic groups of the area around Germany, actually manages to in a sense predict some of the key forces driving the start of World War II. It is this fact, along with its other interesting submaps, extra information, inclusions, and exclusions, that make it a worthy map of the week.

One thing this map demonstrates particularly well is the power of maps to connect somewhat abstract concepts like ethnicity to particular spaces. On a more local level in the places we live, we often connect certain areas of town with particular cultures, but it can be hard to express where one culture ends and another begins spatially. Maps are a particularly powerful tool for authoritatively communicating these spatial relationships: west of this particular line is Dutch, east is German, but to the north we have another line and then the Danes. And in areas where the ethnic divisions are a bit more muddled like the borders of Czechoslovakia, maps can still show this complexity in a clear visual manner as this map does by alternating the colors in a particular pattern; in the legend at the bottom left of this map, this pattern doesn’t even need to be explained as it’s so clear visually what the alternating rectangular sections represent. When trying to relate otherwise abstract regions with similarly abstract concepts, there really is no alternative to maps.

Firstly, I would like to start by saying how professionally this analysis and critique of the map has been done. I enjoyed reading it and learning many new facts. You definitely did not judge the book by its cover and gave a very thorough analysis of the map and its history. I like how you started with general information about the map and the territory it covers and then went deeper into it with historical facts. You gave a good background of the territories prior to the end of World War I and how it was mapped for the British advantage. Furthermore, I liked how you connected WW I and WW II where you gave a description or a setup for what was to expect and what countries the British wanted as allies in order to defeat Germany. Lastly, the explanations of WW II and its borders prior to the end are very educational and informational which you substantiated with many historical facts. A lot of new information can be seen and learned from this map and your analysis. You both showed the advantages and disadvantages of this map and how it was made from the British point of view where they wanted to show and emphasize their point of view; more precisely the view of the British War Officer.

I think Nate could have not picked a much better map. He does a great job going into detail about the specific regions and their intricacies, and how the ethnographic data influenced history. The context is great in relation to our course material and the power of maps. He really went into depth on explaining what Germany is and was. If you look at an ethnographic map of Germany today you can see how much it has changed since 1918. Finally, his tie to the map being created by the British explains why pieces of the map are important, pieces that the reader might not realize otherwise.