Library of Congress Enlarged Version

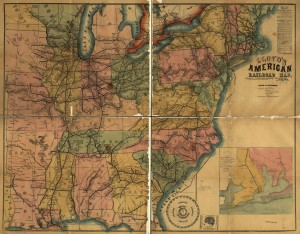

In the spotlight this week is an 1861 map of the extent of the rail system of the United States, entitled ‘Lloyd’s American Railroad Map.’ James T. Lloyd, the cartographer and designer of this map, published many similar maps during the mid 19th century, often depicting travel methods such as roads and railways. This map in particular details the vast, interconnected nature of the American rail system and the towns and cities along each line. Lloyd’s map also contains a timetable showing the time differences between major American cities and an inset image of Pensacola, Florida and its surrounding rail lines and military bases. These interconnected elements of a technologically descriptive map serve to highlight American’s developing industry and transportation abilities. A plethora of vivid rail lines controls the landscape upon which they are built, and translate a sense of closeness and accessibility across the country. At a time when the country was segregated by the Civil War, this map takes a markedly unified look at the country through the lens of technology and industry.

One could look at this map and find its detailed network of rail routes and intricate town labeling impressive on its own. However, there are more elements at play in this map than just detailed drawing. First and foremost, this map shows the prominence and reach of the rail transportation system in America, which carries several connotations. Primarily, it gives the viewer a sense of control over the land in which he or she lives. No longer is there an unknown frontier, and no longer will it take weeks to reach far distances. Everything in the country is within reach, just a train ride away. And with so many towns labeled as stops, it serves to show the variety of location and ultimately quantifies the railroad’s power over land. Also, by truncating the country at the western borders of Missouri and Arkansas, the map gives the impression that the railroads do take up the whole country, despite the remaining half of the country that extends westward. Although this land was just American frontier and not yet demarcated as states, the fact that Lloyd omits its existence in his portrayal of America speaks to his perception, or desired perception, of the railroad in America.

The omission of western land implies future expansion and that while the railroad exists in this half of the country now, it can, and most likely will, soon spread westward. Map historian and cartographer Brian Harley has argued that silences of a map can have just as powerful of an effect on the observer as that which is actually depicted—a strategy Lloyd certainly employs here. The absence, or silence, of this territory, speaks to a subconscious ideology of future control; that is, it is not worth depicting at the time of the production of this map, but will be worth detailing once the railroad, and ultimately the influence of American technology and culture, expands to fill it.

In addition to giving the viewer a sense of the railroad’s influence over territory, this map augments the development of the American geographical imagination itself. As Susan Schulten has noted, the expansion and movement of a culture is matched by maps of the territory into which it expands, promoting civic unity as it depicts the advancement of an entire society. While I doubt even the creator had traveled every one of these rail lines and experienced every single stop along the way, this creation helps the viewer imagine where each stop is, and helps broaden the sense of the American country for any individual. Even the stylistic choice of dark, thick lines representing the railroad affects the geographic imagination in that places do not seem so far from each other. Two railroads that appear close due to the nature of their artistic presentation could in fact be a great distance apart. This darkness and size also gives the illusion of a crowded network of railroads, as if the rail has a greater reach than it actually does.

Another aspect of this map worth noting is not the main feature of the railroads, but of the inset images as well. First, Lloyd includes a time dial based on a time of noon at Washington, D.C, showing the corresponding times in approximately thirty other major cities, both inside and outside of the country. In an age where immediate cross-country communication and satellites did not exist, it would be difficult to synchronize the times between distant towns and cities, making train departure and arrival times different for every location. This time dial that Lloyd includes seems to be an attempt at fixing that issue, and if this map were widely disseminated, so would the standardization of times, which would ultimately benefit rail lines.

Next is the inset of Pensacola, Florida. At first, a viewer today might assume this is included because it did not fit on the larger map, but upon further investigation, this inset serves as a piece of news and current events rather than a geographical addition. The almost overwhelming amount of information provided by Lloyd on this map serves to enhance its authenticity and affirm its accuracy and relevance to the American citizen. During 1861, the Confederate and Union armies fought the Battle of Pensacola, which raged from January to November of that year. Thus, Lloyd includes details of Pensacola’s rail lines and what looks like troop positions in order to give the American people a geographical image to relate to what they hear and experience through the news. As Schulten has emphasized in her writings, the purpose of maps in American History is to emphasize and document the evolution of the nation and to connect with current events and a cultural, national identity—not explore physical terrain. In addition to detailing technology and physical location, Lloyd’s map is a comment on the national atmosphere at a time of war. By contrasting an ordered, unified, and powerful map with a country divided and in disarray, Lloyd makes his projection of the American Railroad an image of comfort and control to the American public. In this way, Lloyd’s map conveys order in a nation of disorder.

I was impressed by your fresh view of the railroad map! After reading your critique, I have a deeper understanding of the American Railroad. I love the the part “silence” of the map in your critique. The ‘not showing part’ emphasis the important country sense. Overall, you combine what we learn in Dr.Barney’s within the critique in the entire essay.The successful connection between what inside the map and what outside the map enables audience to not only focus on the actual detailed information such as the footnotes and colors but also invisible context, cultural elements. GOOD JOB!