By Caterina Erdas

In early March, right before I came home for the rest of the semester, my mother spent two hours explaining new coronavirus precautions to my grandmother, who lives nearby. Her name is Mei-Chih Chang, but we call her Popo (maternal grandmother in Mandarin). My mother laid down the law: Popo could not walk to the Chinese grocery store, go to her church, or interact with anyone outside our family. Popo agreed to her terms.

Later that same day, my mother ran into Popo at the Chinese grocery store.

Popo defended herself: she had to use the bathroom. My mother wasn’t convinced. Back home, my mother, now upset, re-explained the dangers of coronavirus situation and got her siblings to call Popo and yell at her some more. Thankfully, Popo has since learned her lesson.

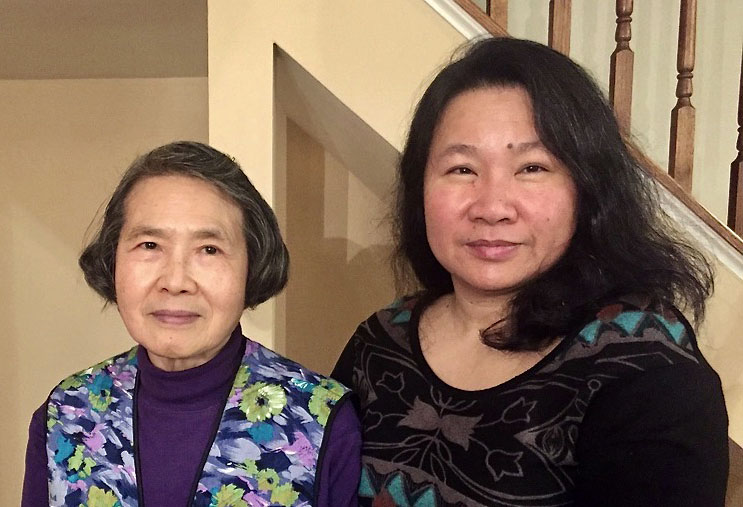

While my mother, Yen-Pei Christy Chang, shares half of her DNA with Popo, their differences outnumber their similarities.

Popo grew up in Taiwan. Her formal education ended after elementary school when she left to take care of her three sisters after their mother died. She was a housewife before she moved, at 39, to Bluefield, West Virginia, where she worked in an electronics factory and as a house cleaner. My mother, who was 12 years old when she immigrated to the US with Popo, has a Ph.D. in Human Genetics, works as a part-time professor at the University of Maryland Medical School and is a clinical psychology student. Sometimes, Popo hugs my mother, looks up at her in awe, and asks, “how did you come from me?”

Popo is now 77 years old. Five years ago, she moved into a nearby condo so my mother could take her to lung specialists. She suffers from bronchiectasis, a respiratory disease.

“About a third of her lungs are scarred and no longer elastic,” my mother explained. “So it is harder for her to fight off infection and expel air, and she has reduced lung capacity.” Popo has short periods of heavy coughing multiple times a day. Laughing, strong smells, smoke, and getting surprised can all set them off. Deep breaths trigger coughing as well, so her breathing is shallow and sound like frequent sniffing.

When my mother heard the coronavirus was in the U.S., she was concerned about Popo.

If she were infected, “there is almost no chance she would survive,” my mom said. “But for her to maintain a certain standard of living, she needs to take long walks. If she is walking, she will naturally exercise her lungs. So if we isolate her, it would comprise her health. If she walks and doesn’t interact with anyone outside our family, it’s the safest for her.”

Three of my mother’s co-workers have lost someone to coronavirus. She knows that Popo may be the one she loses to COVID-19.

“I am not so upset because I know eventually, something will compromise her health. Because she actively prays to God to go back to her Heavenly Father, I know that she won’t be resentful or disappointed that her life is ending. That gives me some peace of mind. Popo wants autonomy, it’s not stubbornness or a desire to make me more worried. I have to respect that in her. But it’s a difficult adjustment for anybody starting to take over as caretaker instead of being the child.”

With my mother translating, I asked Popo if she is scared of contracting COVID-19.

“I am not thinking about myself at all. Every time I go to sleep, I think, ‘this may be the last time I open my eyes. That’s fine. I am ready at any time to go.’ Every morning I wake up I think, ‘Oh, God wants me to live another day.’ I thank him and go with my day. But if I didn’t get that day, I would be happy.”

“I am the Popo, she is the Mama (referring to my mother), and you are the granddaughter. We are all family; we are all really the same person.”

In the interview below, my grandmother and mother talk about the grocery store incident in Mandarin.