Fresh, beautiful, bright green grass, overlooking a river lined with groups of families and friends fishing, may not seem like anything more than a park when you first stumble upon it. That is, until the moment you notice the small rectangular bronze plaques reading, “Richmond Slave Trail,” scattered along the three-mile walking route.

On a radiant 80-degree April afternoon, I set out to relive this narrative myself. When I arrived at the Manchester Docks, the trail’s starting point, I was met by people of all ages unloading their fishing rods and coolers from the trunks of their cars, preparing for what I’m sure was going to be a pleasant next few hours for them. After all, it’s fairly easy to walk right past the signage commemorating the Richmond Slave Trail.

If visitors paused for a minute to read what the trail’s first sign, though, they’d quickly learn that this charming place once operated as a large-scale port in the vast upriver slave trade, allowing Richmond to become the main source of enslaved blacks on America’s east coast from 1830 to 1860.

Composed of flat land surrounded primarily by trees, bushes and shrubs, the narrow dirt and leaf-filled path first led me through several short wooden bridges to slight openings in the woods, from which I could see across the James to Shockoe Bottom, where human beings are assumed to have been auctioned off by the thousands every month in the decades before the Civil War. These numbers are constantly fluctuating, as the available data about the domestic slave trade is regularly reassessed.

The 17 markers that outline the Richmond Slave Trail either identify different areas in Richmond that played a role in the Trans-Atlantic slave trade, such as Mayo’s Island and the James River and Kanawha Canal, or explain underlying themes and concepts of slavery, such as the use of arms and the despair carried by these people.

Samantha Seeley, an assistant professor of history at the University of Richmond and expert in race, slavery and freedom in early America, sees this trail as an essential element in understanding the history of slavery in Virginia.

“I think, obviously, studying the past is really important to thinking about the problems of our present,” Seeley said. “That’s always been my line. In terms of the site itself, I also agree with what a lot of community activists have been saying: That slavery was everywhere in Shockoe Bottom, and so the trail is wonderful as a kind of place to start, but I’d actually like to see the whole space preserved and made into a kind of memorial park or a site of conscience for people to go and think about this past more deeply because I think just the small markers, you can easily walk by.”

Ideally, Seeley would want the comfort of knowing that a larger space, perhaps covering more of Shockoe Bottom, is being preserved for future generations to avoid this grim past being forgotten, as has been happening for many of Richmond’s citizens today. Seeley would also prefer that the black community in Richmond control this process, rather than Richmond City Hall.

Though she is unsure of the exact amount of enslaved Africans who passed through Richmond, Seeley explained that out of the 300,000-350,000 people who were sold from Virginia during the domestic slave trade, many, if not most, would have come through Richmond, as the city was the major market for the sale of slaves in the upper south.

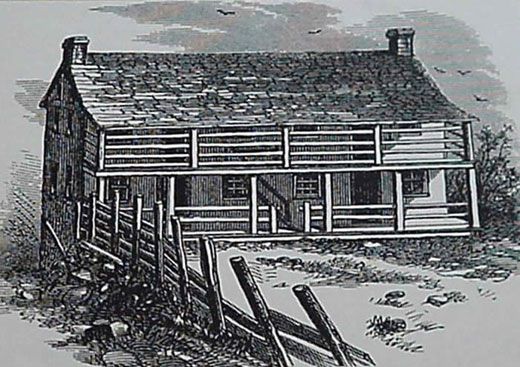

The trail extends into downtown Richmond, where its last few stops mark Lumpkin’s Jail, Richmond’s African Burial Ground and the first African Baptist church. Lumpkin’s Jail, also known as the Devil’s Half Acre, was a compound owned by Robert Lumpkin that contained a slave holding facility, lodging for slave traders, an auction house and a residence for Lumpkin and his family.

Derek Miller, assistant director of community relationships and community-engaged learning at the University of Richmond, explained the significant distinction between the location’s two names.

When people began excavating the site, they referred to it as Lumpkin’s Jail because of its past as a slave warehouse owned by Lumpkin.

“In calling it that, you’re privileging the slave owner in putting his name as preeminent, and you’re privileging this idea of ownership of property, which fits into classic American notions,” Miller said. “In reality, the enslaved population and African American community began referring to the site almost immediately as the ‘Devil’s Half Acre.'”

Robert Lumpkin was a notoriously harsh slave owner, so by calling it the ‘Devil’s Half Acre’ a different story is being elevated and presented, Miller said.

“As you move through the city of Richmond, what do you see?” Miller asked me. “You see these monuments, right? You see these beautiful homes, right? Well, who owned the historic homes of Monument Avenue? Whose story do you not see? Whose story is not told here?”

By not making the story of the enslaved visibly present, Miller stressed that the significance of the slaves during this time period gets ignored and all the dark places and hard-to-tell portions of the narrative are suppressed and later forgotten.

Currently, the Lumpkin’s Slave Jail Site Project is underway. This is a collaborative effort by the City of Richmond, the Richmond Slave Trail Commission, teams of people and groups, who have worked together and will continue to do so, to preserve the history of enslavement in Richmond.

As an anthropologist and dedicated member of RVA Archaeology, Miller values the Richmond Slave Trail because it asks people to experience Richmond through a different lens than they normally would.

Miller explained that, while walking down the trail, his own perspective is influenced by his background and knowledge.

“I’m always looking at the ground waiting to see what pops up,” he said. “As everybody walks, they dig a little bit deeper and things just start coming up from it. But for me, I’m always stuck thinking about these historical trends and then trying to think, ‘how is that shaping our lives today?’”

I might have overlooked the trail’s signs myself, had I not known beforehand where I was going. But as the economic engine of the region as a whole during a time when enslaved Africans were pouring in and out of Richmond, the James and its role within a century characterized by its inhumanity cannot be denied or disregarded.