by Lucy Nalen

Standing outside Sixth Mount Zion Baptist Church, Benjamin Ross, church historian, speaks to me through gusts of wind that push and pull at his trademark bow tie.

Ross, an impeccably dressed man, has given this spiel before, and it’s apparent in the rushed and rehearsed tone of voice he uses. He knows his stuff.

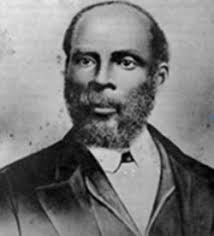

Sixth Mount Zion was the brainchild of a famous black preacher, John Jasper, who founded the little church in a horse stable down by the James River, two years after the end of the Civil War in 1867. Today the church stands as a steadfast symbol and cultural landmark of Richmond’s Jackson Ward.

Jasper, who lived from 1812 to 1901, founded the church when he was 55. He had a vivid and dramatic oratory style that drew people from all over Virginia, and parts of the Northeast, to hear him preach.

“Jasper was very very popular,” Ross told me. “No question about it.”

His congregation quickly outgrew the stable, and in 1869 Jasper purchased a small chapel on Duval Street, where the church still stands today. Once there, Jasper’s fame skyrocketed when he began giving a fiery sermon premised on a controversial claim: that the sun orbited the earth, in accordance with scripture. By 1887, Sixth Mount Zion counted 2,500 members.

“If you lived in Richmond during that time, you came to hear the ‘Sun Do Move’ sermon,” Ross said. Jasper went on to deliver the sermon 273 times, drawing crowds and press coverage to his church, and to other locations where he traveled to preach.

Thirteen years after purchasing the small chapel on Duval Street, the congregation had again outgrown the building. The chapel was torn down and rebuilt in 1890.

In 1925 a well-known black architect, Charles Russell, partnered with a talented black contractor and builder, Lincoln Bailey, and erected the church that stands today by building around the 1890 structure. Today’s Sixth Mount Zion church is a prime example of Russell and Bailey’s Normal Gothic style.

As Jackson Ward thrived in the 1930’s and after World War II, Sixth Mount Zion kept pace, led by a powerful black congregation that was taking part in the glory that was Jackson Ward.

This all came to a painful halt in 1957, when work began on the Richmond-Petersburg Turnpike, later to become Interstate 95. Uncomfortable with Jackson Ward’s growing power, Richmond’s white politicians chose to route the highway straight through Jackson Ward.

The neighborhood experienced an immediate decline, with homes destroyed and families forced to move. Sixth Mount Zion began losing significant numbers of its congregation. Then they got even more bad news when planners announced that the church stood in the direct path of the planned highway.

“No matter how they tried to redesign the highway, the church was always in its path,” Ross said, shaking his head.

The church was given three options: Tear down the building and receive compensation to build a new church elsewhere; move the church; or fight to keep the church where it was.

The congregation chose the third option, and in the end highway planners relented. “They swung the highway around the church,” Ross said. “We were happy about it, but it was a bittersweet victory.”

Hundreds of homes were demolished to make way for the highway, and many of those residents were members of the church, leaving Sixth Mount Zion with a significant hole in their beloved congregation.

“It’s like a pendulum,” Ross explained. “Neighborhoods develop, and then they swing back into decline, and then they make progress again. We’re doing very well right now.”

As Ross and I entered the church to take shelter from the violent winds outside the church, his voice changed and lost its rehearsed tone. Entering the closet-sized room that functions as the church’s museum, Ross opened up about his life with Sixth Mount Zion.

“My family were members of this church,” he said. “I’ve been coming here for fifty years.”

He’s lived through the ebb and flow of the church’s congregations, and it’s left him with a passion for the church that earned him the respect of his fellow parishioners, and eventually turned into a vocation.

When the previous historian retired in 2008, she nominated Ross as her successor. Church leaders and members of the congregation gave him their wholehearted support.

When the previous historian retired in 2008, she nominated Ross as her successor. Church leaders and members of the congregation gave him their wholehearted support.

“I didn’t just sneak into this role,” Ross said. “I was voted into it in a church meeting!”

Today Ross welcomes daily visitors, including many tourists, to the historic church, and travels around the country to speak at conferences about the history of Sixth Mount Zion.

The icing on the cake?

“It’s turned out to be really, well, fun.”

And with that, Ross adjusts his bow tie and locks the door to his sanctuary in the basement of Sixth Mount Zion Baptist Church.