Despite having integrated downtown night courses in 1964, the University of Richmond remained segregated on its main campus until 1968. Early that year the Board of Trustees approved a measure to accept federal funding for projects outside of capital construction. In part, the funding meant that the University had to comply with federal statutes such as the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The act prohibited discrimination on the basis of race, color, or national origin in any program receiving federal funds. Although the aid would not have been available until the following school year the University had to prepare to meet prerequisite qualifications for certain grants. Part of those prerequisite qualifications was compliance with the Civil Rights Act. During this time attitudes toward integration on campus greatly differed with some calling for swift action and others dragging their feet into the inevitable.

Despite having integrated downtown night courses in 1964, the University of Richmond remained segregated on its main campus until 1968. Early that year the Board of Trustees approved a measure to accept federal funding for projects outside of capital construction. In part, the funding meant that the University had to comply with federal statutes such as the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The act prohibited discrimination on the basis of race, color, or national origin in any program receiving federal funds. Although the aid would not have been available until the following school year the University had to prepare to meet prerequisite qualifications for certain grants. Part of those prerequisite qualifications was compliance with the Civil Rights Act. During this time attitudes toward integration on campus greatly differed with some calling for swift action and others dragging their feet into the inevitable.

Conversely, the Department of Health, Education and Welfare (HEW), one of the federal agencies charged with enforcing the Civil Rights Act of 1964, was steadfast and exacting in its mission to integrate schools. HEW officials in Virginia began pressuring the University to integrate not only its student body but also its faculty. An editorial published in The Collegian on September 20, 1968 echoed HEW’s plea for faculty integration. Writing on behalf of The Collegian staff, this editorialist noted that The Collegian’s stance on integration was not meant to be seditious or in vogue with the times but rather earnestly rooted in the belief that University of Richmond students did not have enough contact with people of other races and “have never been fortunate enough to really get to know the educated Negro.” The editorialist went on to contend that the university could not claim to be liberal arts if it did not expose students to those of different “races, creeds, colors and social backgrounds.”

Interestingly, the editorialist made no appeal to claims of justice or civil rights even though the push for integration of any kind was propelled by civil rights legislation. Moreover, the piece presents white students as the main beneficiaries of faculty integration and does not address the implications of this on black faculty. The sentiment there is ‘if we hire black faculty or do a faculty exchange with a historically black college or university then all will be well.’ The piece does little to nuance the argument and paints the issue as black and white.

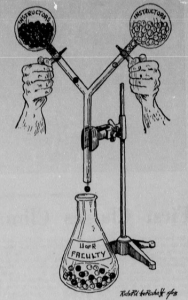

The accompanying cartoon functions similarly. The artist chose to depict faculty integration with scientific imagery. In the image an apparatus holds two glass bulbs labeled “instructors”. One bulb contains black molecules and the other contains white molecules, which are taken to represent black and white faculty respectively. At the bottom of the image a flask labeled “U of R Faculty” contains a fairly equal mix of both black and white molecules. The choice to represent faculty integration with an image that evokes scientific study suggests that there can be a “science” to the process in a way that strips the problem of its context and sordid history. The hands with no body attached also evoke a detachment from the lived human experience of fighting for integration. Although the written piece makes appeals to humanity and improvement thereof, the appeals are limited to conceptualizations of white humanity. Both the editorial and the cartoon function to create the illusion of an alchemy of integration in a way that does not humanize the actual experience of integration for black people.

The accompanying cartoon functions similarly. The artist chose to depict faculty integration with scientific imagery. In the image an apparatus holds two glass bulbs labeled “instructors”. One bulb contains black molecules and the other contains white molecules, which are taken to represent black and white faculty respectively. At the bottom of the image a flask labeled “U of R Faculty” contains a fairly equal mix of both black and white molecules. The choice to represent faculty integration with an image that evokes scientific study suggests that there can be a “science” to the process in a way that strips the problem of its context and sordid history. The hands with no body attached also evoke a detachment from the lived human experience of fighting for integration. Although the written piece makes appeals to humanity and improvement thereof, the appeals are limited to conceptualizations of white humanity. Both the editorial and the cartoon function to create the illusion of an alchemy of integration in a way that does not humanize the actual experience of integration for black people.