by Eden Wolfer

Eden Wolfer is a rising junior from Wilmington, Delaware. She is majoring in sociology and minoring in education. This is her first summer working for the Race & Racism Project and she is excited to learn from this experience.

The entrance to the Poplar Forest plantation home is well marked from the residential road in Lynchburg, but it is really just a long gravel road through the woods with an occasional glimpse of a golf course to the right and empty fields to the left. There is nothing to indicate you did not drastically mess up somewhere in the last two and a half hour trip. Eventually, the trees part and you can see the beautiful brick facade of Poplar Forest. The property consists of a gift shop, two barns, converted offices, and the actual plantation home; all making up Thomas Jefferson’s retreat plantation.

The entrance to the Poplar Forest plantation home is well marked from the residential road in Lynchburg, but it is really just a long gravel road through the woods with an occasional glimpse of a golf course to the right and empty fields to the left. There is nothing to indicate you did not drastically mess up somewhere in the last two and a half hour trip. Eventually, the trees part and you can see the beautiful brick facade of Poplar Forest. The property consists of a gift shop, two barns, converted offices, and the actual plantation home; all making up Thomas Jefferson’s retreat plantation.

The gift shop, where you buy your tickets along with all of your Jefferson memorabilia, leads to a room that shows a thirteen minute video. The video plays every half hour and features a Jefferson reenactor speaking to the audience as a rambling old man talking about his vacation home property. From the moment I walked into that room, I was prepared to be upset at the lack of narratives of enslaved people. The only display in the room was titled “Pieces of Everyday Life: The Archaeology of Enslavement” and it included artifacts, like coins, buttons, and broken pipes, that showed the limited rations given to the enslaved people as well as how they made the best of the awful situation. I readjusted my expectations of a totally Jefferson-centric white washed version of Poplar Forest, but in my mind clearly this was going to be the only time slavery was talked about on this plantation tour.

The gift shop, where you buy your tickets along with all of your Jefferson memorabilia, leads to a room that shows a thirteen minute video. The video plays every half hour and features a Jefferson reenactor speaking to the audience as a rambling old man talking about his vacation home property. From the moment I walked into that room, I was prepared to be upset at the lack of narratives of enslaved people. The only display in the room was titled “Pieces of Everyday Life: The Archaeology of Enslavement” and it included artifacts, like coins, buttons, and broken pipes, that showed the limited rations given to the enslaved people as well as how they made the best of the awful situation. I readjusted my expectations of a totally Jefferson-centric white washed version of Poplar Forest, but in my mind clearly this was going to be the only time slavery was talked about on this plantation tour.

At the end of the video, our tour guide came in and began: “Jefferson designed this house but it was built by slaves,” which, given my assumption that this was going to be a Thomas Jefferson romanticization from the beginning, was really not what I was expecting to hear. The tour guide explained that the house had been built from Jefferson’s designs by John Hemings who, although enslaved, was one of the most sought after designers of the era. In fact, while Jefferson did not pay Hemings for the Poplar Forest project, he often sent John to other people’s construction sites where both Jefferson and Hemings made money off his work. At this point I decided to throw out all of my expectations.

After his presidency, Thomas Jefferson was forced by the social rules of the time to provide housing and hospitality to those who came onto Monticello to gawk at the retired president. Jefferson had no patience for that and decided to build a retreat home for when he was overwhelmed, and took some of his slaves down to Poplar Forest to run the house and work in the tobacco and wheat fields. He oversaw construction on his ridiculously difficult to build octagon design but, as fit his place in society, he never lifted a finger.

The real genius behind the perfectly symmetrical octagonal design was John Hemings. The house is meticulous, the measurements perfect in ways that are difficult to accomplish with modern tools and seem impossible having seen the tools available at the time. The house is in the process of being restored. There was a fire that gutted the house in 1845. The plaster is all new and in one room they decided not to replace it to show the intricate brickwork. The house is made of somewhere between 42 and 48 thousand hand made bricks, all made by John Hemings and the other enslaved workers. They are perfectly assembled, angled, and measured to fit Jefferson’s octagonal house.

The real genius behind the perfectly symmetrical octagonal design was John Hemings. The house is meticulous, the measurements perfect in ways that are difficult to accomplish with modern tools and seem impossible having seen the tools available at the time. The house is in the process of being restored. There was a fire that gutted the house in 1845. The plaster is all new and in one room they decided not to replace it to show the intricate brickwork. The house is made of somewhere between 42 and 48 thousand hand made bricks, all made by John Hemings and the other enslaved workers. They are perfectly assembled, angled, and measured to fit Jefferson’s octagonal house.

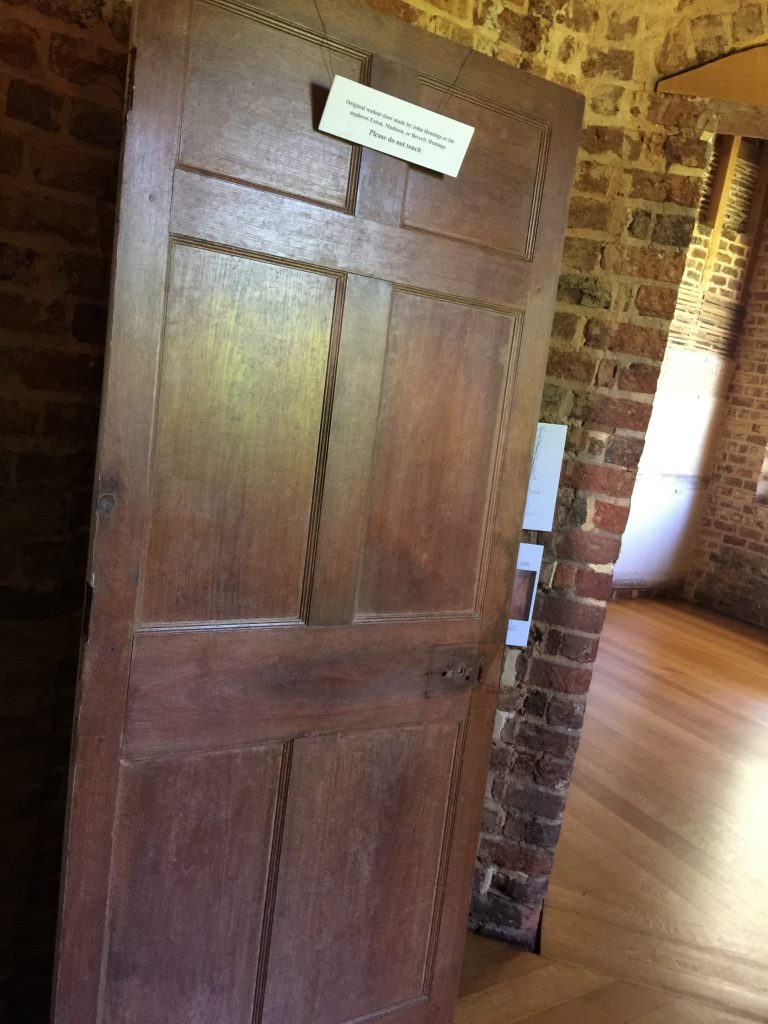

The tour guide showed us how wooden wedges were put in between the bricks to act as places where things could be nailed into the wall. John Hemings personally made all of the furniture and doors in the house, all ingeniously designed to show no nails or seams. The reproductions were made with modern tools and were still excruciatingly difficult to make. The only original door in the house, which was made using nothing but hand tools, is exactly the same quality of those made with laser levels and power tools.

The tour guide showed us how wooden wedges were put in between the bricks to act as places where things could be nailed into the wall. John Hemings personally made all of the furniture and doors in the house, all ingeniously designed to show no nails or seams. The reproductions were made with modern tools and were still excruciatingly difficult to make. The only original door in the house, which was made using nothing but hand tools, is exactly the same quality of those made with laser levels and power tools.

The tour guide was reverent as he explained to our group that in reading into the architecture of the house, we can tell that some of Jefferson’s slaves, at least the builders, knew complex mathematics, geometry and trigonometry. This house is a tribute to the intelligence and hard work of enslaved people like John Hemings.

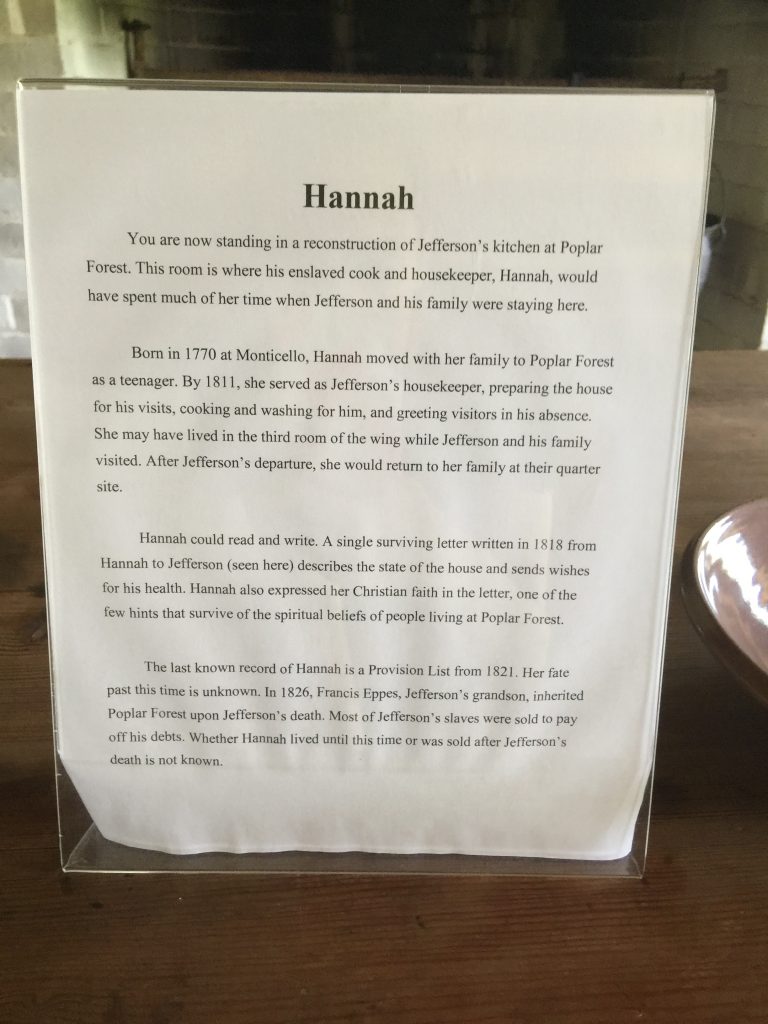

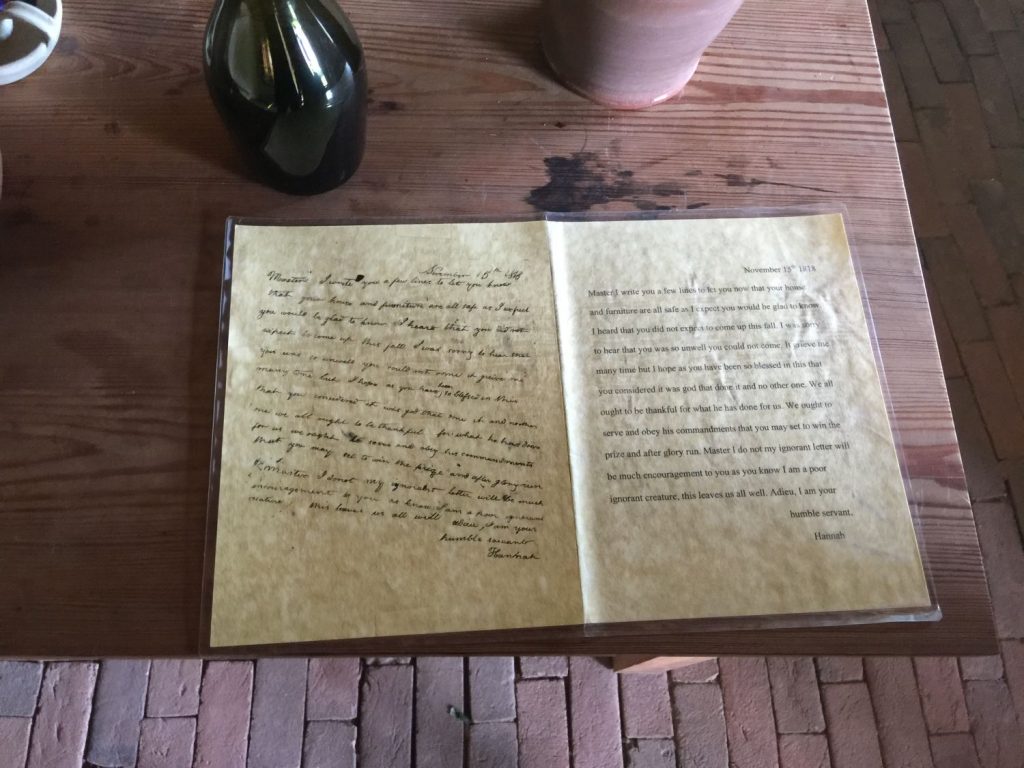

A note that I will add about the experience though, is that the difficulties of slavery were pushed under the rug. John Hemings was Sally Hemings’ half brother but her name was never mentioned until I directly asked the head of programing. Other enslaved people were mentioned: Hannah, the literate chef who was acting lady of the house when Jefferson was at Monticello, John’s nephews, Eston, Madison, and Beverly, who also shared blood with Sally, and a man who was paid twenty-five dollars, the equivalent of about a thousand today, to dig a giant hole and make two symmetrical mounds beside the house.

The displays told stories of how Jefferson was a kind slave owner who allowed slaves to make a little money on the side or get married, even though it was illegal in the eyes of the state. There was a section on the property that showed the frame of what the home of an enslaved person would have looked like. No matter how kind Jefferson may have been to the Hemings family, telling only those stories is not the same as telling the stories of the enslaved people on Poplar Forest, those who worked in the fields and were controlled by overseers. While I was beyond impressed that such a huge focus was put on the work and intelligence of John Hemings, I hope that as the renovations are made and the site is expanded so more narratives can be told.