by Rena Xiao

Rena Xiao is a rising junior from New York City who has spent the majority of her life living abroad in Beijing, China. She is a Double Major in Geography and Global Studies with a Concentration in World Politics and Diplomacy, and a minor in WGSS.

If you did not attend school in the United States, you most likely have not learned much about the Civil War. Everything I know about American history mostly starts around World War I. For a U.S citizen, I know embarrassingly little history about the county I am from. I attend school in Richmond, Virginia, a city where perhaps some of the most notable events that have shaped America occurred in this city. From Patrick Henry’s “Give Me Liberty or Give Me Death” speech at St. John’s church in 1741 to being the capital of the confederacy, every corner of the city is packed full with historic events. My international school curriculum did not touch upon the founding of the country or the war that would divide it in two. I entered the American Civil War Museum as a novice, eager to learn with the knowledge base equivalent of a foreigner or international tourist.

If you did not attend school in the United States, you most likely have not learned much about the Civil War. Everything I know about American history mostly starts around World War I. For a U.S citizen, I know embarrassingly little history about the county I am from. I attend school in Richmond, Virginia, a city where perhaps some of the most notable events that have shaped America occurred in this city. From Patrick Henry’s “Give Me Liberty or Give Me Death” speech at St. John’s church in 1741 to being the capital of the confederacy, every corner of the city is packed full with historic events. My international school curriculum did not touch upon the founding of the country or the war that would divide it in two. I entered the American Civil War Museum as a novice, eager to learn with the knowledge base equivalent of a foreigner or international tourist.

The first thing I learn about the Museum is that it is closing this September or more accurately, the museum in its current location and form will be shutting down. The Museum and White House of the Confederacy is part of a larger consortium of the American Civil War Museums. The Museum at Historic Tredegar, a fellow American Civil War Museum in downtown Richmond, is under renovations where a new building will house the Museum of Confederacy’s Civil War exhibits and artifacts. From a visitor’s experience, I am in favour of the changes made towards moving to a new space. The subject matter of the museum is of course quite dark and heavy and the building structure reflects that. This new Historic Tredegar site promises an extensive remodeling of the exhibits and provides a larger space for the current artifacts and material.

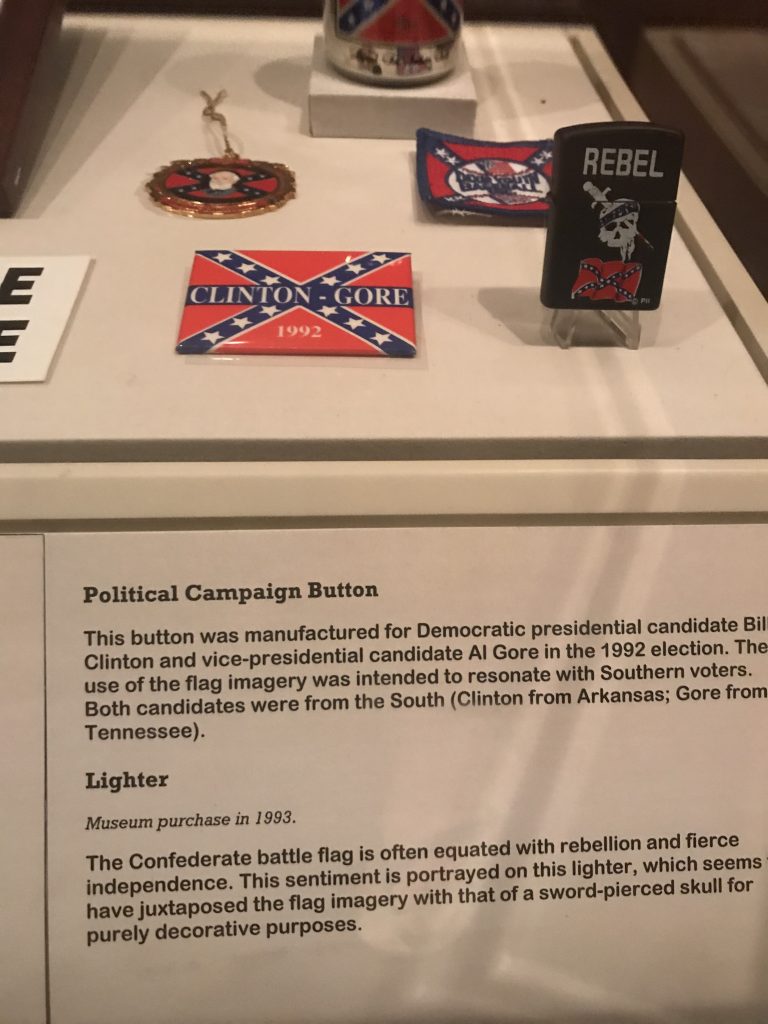

The museum has a difficult task of balancing between presenting information without an accusatory or judgemental tone but also condemning the actions and reasons of the Confederacy. Slavery and the daily existence of people of colour is only a brief blip within the overall exhibitions. This is perhaps the most crucial information of the Confederate Army and American Civil War, but little exhibition space explores the more explicit and unsavoury details. Furthermore, in certain exhibits (see pictured) the captions and context of museum information is favourable towards the “heroism” or “bravery”of Robert E. Lee, Stonewall Jackson and the Confederate Army. Less focus is placed on Ulysses S. Grant and the Northern side, nor is the same positive, praising language used to describe their war efforts.

The museum has a difficult task of balancing between presenting information without an accusatory or judgemental tone but also condemning the actions and reasons of the Confederacy. Slavery and the daily existence of people of colour is only a brief blip within the overall exhibitions. This is perhaps the most crucial information of the Confederate Army and American Civil War, but little exhibition space explores the more explicit and unsavoury details. Furthermore, in certain exhibits (see pictured) the captions and context of museum information is favourable towards the “heroism” or “bravery”of Robert E. Lee, Stonewall Jackson and the Confederate Army. Less focus is placed on Ulysses S. Grant and the Northern side, nor is the same positive, praising language used to describe their war efforts.

The experience in the museum fueled an interest in the history of the North and the Union Army. Visiting the museum leaves a funny, almost uncomfortable feeling in the pit of your stomach. Perhaps one of the main reasons is that it is the Museums of the Confederacy, focusing purely on one side of the American Civil War, a history that too this day certain people will glorify or attempt to justify. However, it turns out most Civil War museums in America are focused on the Confederacy. Richmond is not the only Civil War museum in existence, several other places in the South are dedicated to sharing the history and “legacy” of the Southern states. A staff member informed me only in the Southern states were there entire museums dedicated to the Civil War and Confederate history. This is perhaps a good indication of how figures like Robert E. Lee and Jefferson Davis are remembered in the public imagination: communities in the South minimise traumatic periods of history as events of the past with no lasting repercussions.

The experience in the museum fueled an interest in the history of the North and the Union Army. Visiting the museum leaves a funny, almost uncomfortable feeling in the pit of your stomach. Perhaps one of the main reasons is that it is the Museums of the Confederacy, focusing purely on one side of the American Civil War, a history that too this day certain people will glorify or attempt to justify. However, it turns out most Civil War museums in America are focused on the Confederacy. Richmond is not the only Civil War museum in existence, several other places in the South are dedicated to sharing the history and “legacy” of the Southern states. A staff member informed me only in the Southern states were there entire museums dedicated to the Civil War and Confederate history. This is perhaps a good indication of how figures like Robert E. Lee and Jefferson Davis are remembered in the public imagination: communities in the South minimise traumatic periods of history as events of the past with no lasting repercussions.