by Kristi Mukk

Kristi Mukk is a rising senior from Mililani, Hawaii. She is majoring in Rhetoric and Communications and minoring in English. She is a dancer and communications director for Ngoma African Dance Company. This is her first time working for the Race & Racism Project as a Summer Fellow, and she is excited to continue her work in the course Digital Memory & the Archive in Fall 2018.

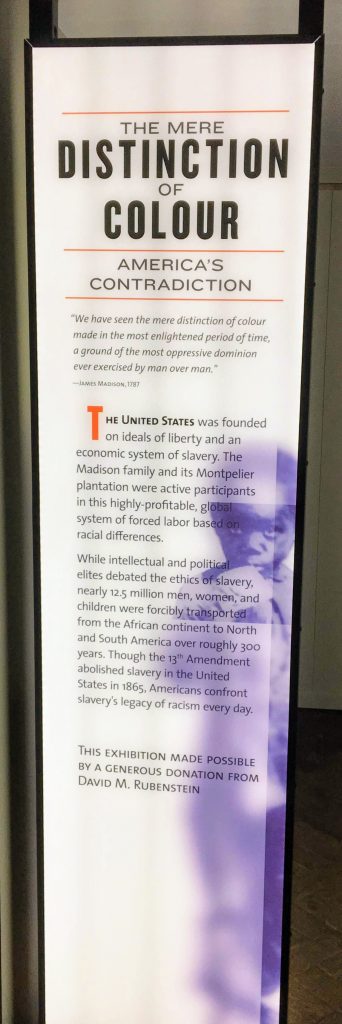

The Mere Distinction of Colour exhibit at James Madison’s Montpelier opened to the public on June 5, 2017 and is located in the cellars under the mansion. The exhibit invites visitors to confront the great American paradox of the reality of slavery in a country that values liberty and freedom. Enslaved people played a large role in the lives of James and Dolley Madison. James Madison grew up around enslaved people working on the Montpelier plantation, and they were part of his birthright when his father passed away. Dolley Madison utilized the skills of the enslaved people to uphold her social status. James Madison served as president of the American Colonization Society, a group which sought to send free blacks to Africa as an alternative to emancipation in the United States. At the time of James Madison’s death, there were about 120 enslaved people at Montpelier. After his death, the enslaved people were not freed, but sold by Dolley Madison due to her financial situation.

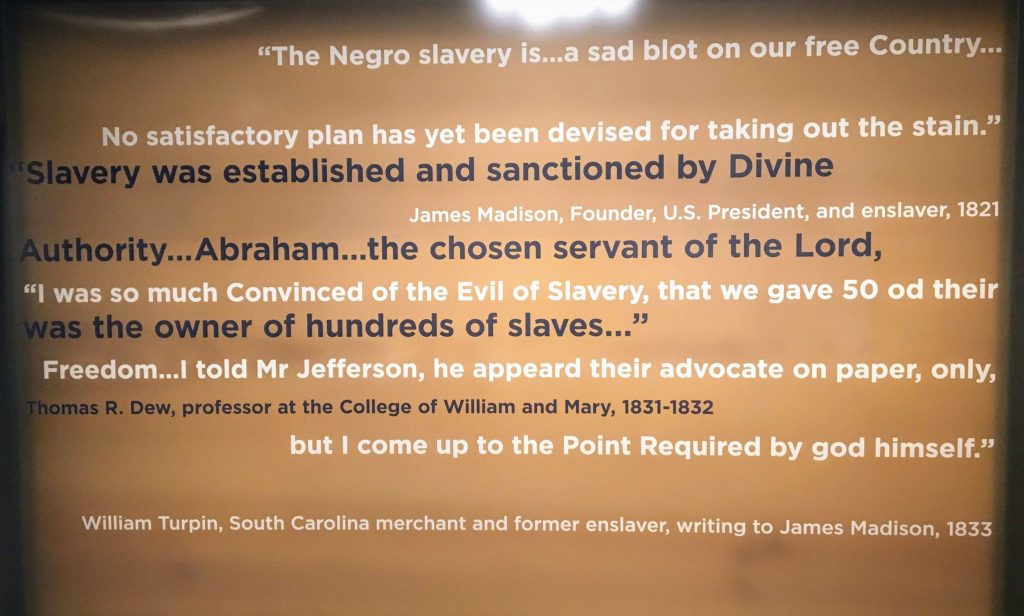

The Mere Distinction of Colour exhibit is divided into two parts. The first part describes the significant economic impact of slavery on the American economy and provides context of the opinions and debates of various people of the time about the institution of slavery. Madison considered slavery “a sad blot on our free Country,” and although he did not believe in inferiority based on the color of your skin, he believed that white prejudice would prevent blacks and whites from coexisting peacefully. The exhibit also confronts the very legacy of James Madison, the Father of the Constitution, by displaying the way that the Three-Fifths Compromise and Fugitive Slave Acts protected the institution of slavery. Rather than thinking of slavery as history that is disconnected from the present, visitors are forced to grapple with difficult questions about how the legacy of slavery affects current events and conversations of race, human rights, and how difficult history is often ignored. A multi-screen video connects the legacy of slavery to the present day crisis of police brutality, poverty in black communities, and mass incarceration. Although some visitors may feel uneasy about confronting the difficult history of slavery, sometimes it is necessary to “re-break the bone in order for it to heal correctly,” as a video in the exhibit stated.

The Mere Distinction of Colour exhibit is divided into two parts. The first part describes the significant economic impact of slavery on the American economy and provides context of the opinions and debates of various people of the time about the institution of slavery. Madison considered slavery “a sad blot on our free Country,” and although he did not believe in inferiority based on the color of your skin, he believed that white prejudice would prevent blacks and whites from coexisting peacefully. The exhibit also confronts the very legacy of James Madison, the Father of the Constitution, by displaying the way that the Three-Fifths Compromise and Fugitive Slave Acts protected the institution of slavery. Rather than thinking of slavery as history that is disconnected from the present, visitors are forced to grapple with difficult questions about how the legacy of slavery affects current events and conversations of race, human rights, and how difficult history is often ignored. A multi-screen video connects the legacy of slavery to the present day crisis of police brutality, poverty in black communities, and mass incarceration. Although some visitors may feel uneasy about confronting the difficult history of slavery, sometimes it is necessary to “re-break the bone in order for it to heal correctly,” as a video in the exhibit stated.

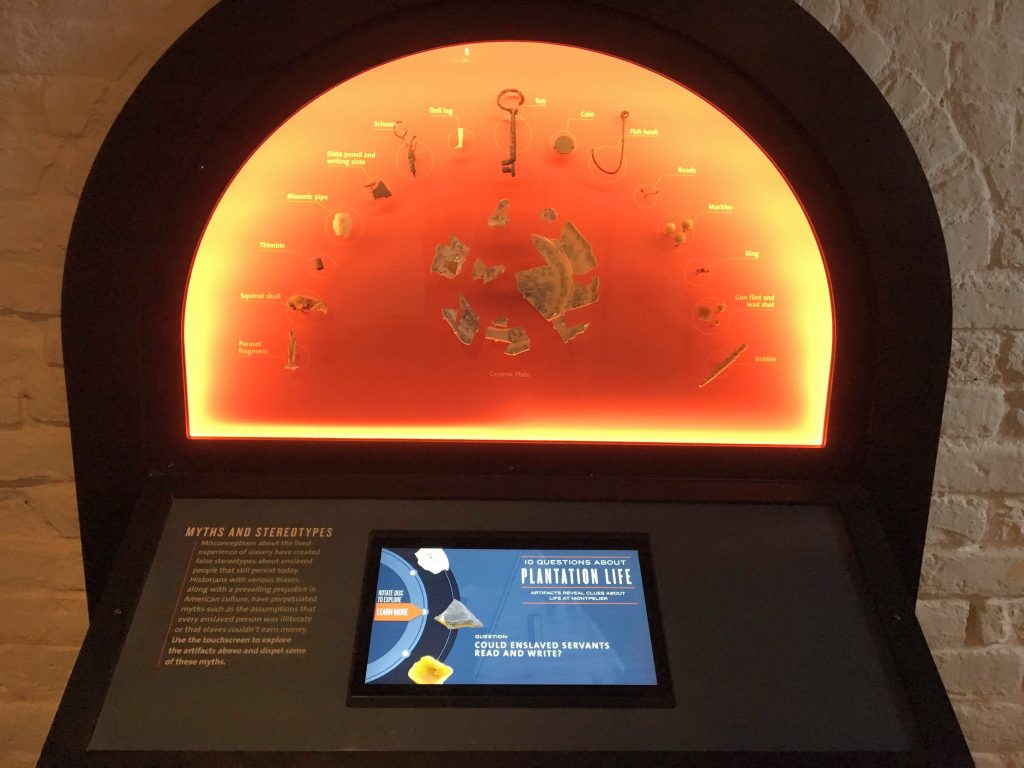

The second part of the exhibit focuses more on the descendants of the enslaved people and gives voices, names, and faces to those who were enslaved at Montpelier. According to Terry Brock, senior research archaeologist at Montpelier, the effort to tell the stories of the enslaved people and to reach out to the descendant community was a bottom-up effort from the archaeologists that were finding artifacts of the enslaved people at Montpelier. These artifacts are used in the exhibit to debunk myths about slavery and give visitors a glimpse into the daily lives of enslaved people at Montpelier. The exhibit confronts the notion of “person or property” and tells of the resilience, strength, and humanity of the enslaved. Visitors are confronted with the realities of life as an enslaved person who can be separated from your family at any time. A video in the exhibit tells the story of Ellen Stewart, an enslaved person whose family was divided after her family members were sold away from Montpelier by Dolley Madison.

The second part of the exhibit focuses more on the descendants of the enslaved people and gives voices, names, and faces to those who were enslaved at Montpelier. According to Terry Brock, senior research archaeologist at Montpelier, the effort to tell the stories of the enslaved people and to reach out to the descendant community was a bottom-up effort from the archaeologists that were finding artifacts of the enslaved people at Montpelier. These artifacts are used in the exhibit to debunk myths about slavery and give visitors a glimpse into the daily lives of enslaved people at Montpelier. The exhibit confronts the notion of “person or property” and tells of the resilience, strength, and humanity of the enslaved. Visitors are confronted with the realities of life as an enslaved person who can be separated from your family at any time. A video in the exhibit tells the story of Ellen Stewart, an enslaved person whose family was divided after her family members were sold away from Montpelier by Dolley Madison.

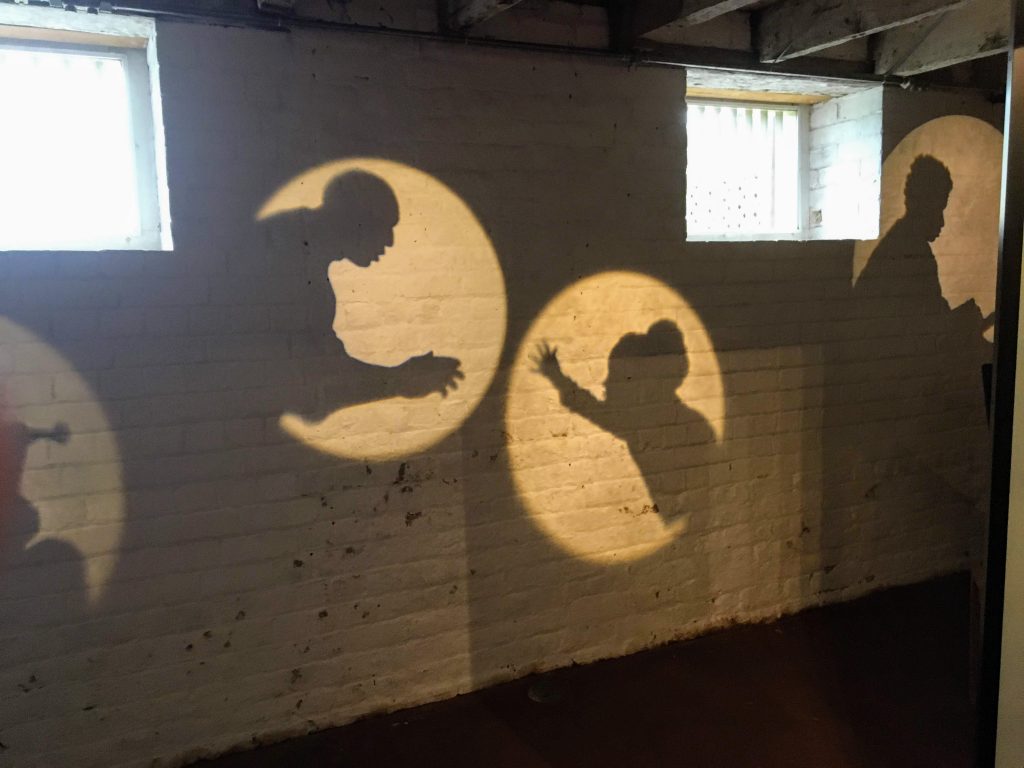

Montpelier has done an exemplary job at presenting the difficult history of slavery and the relationship of Founding Father James Madison to the institution of slavery. Combining archaeology, oral histories, technology, art, and historical fact in this interactive exhibit causes visitors to navigate questions of the connection between the legacy of slavery in the past to the present-day injustices against black people. A denial of the institution of slavery is itself a form of racism as it denies the acknowledgement of the injustices against the enslaved people and the feelings of their descendants. Montpelier’s efforts to involve the descendant community in the creation of this exhibit and the telling of the stories of their ancestors is something that other historical sites should emulate as well. Montpelier also offers archaeological digs that the general public can get involved in so that they can have a hands-on experience with artifacts. The archaeologist-activists of Montpelier have succeeded at telling a more inclusive history—a more complete history of Montpelier that includes the voices of the enslaved people and not just the privileged. By involving both the descendent community and the general public in the creation of public memory, they have expanded public consciousness about the past and connected it to the present. An acknowledgement of the horrific legacy of slavery is necessary for America to heal and become a more just and equitable place for all in the future.