by Jacob Roberson

Jacob Roberson is a rising senior on the varsity football team from Richmond, VA double majoring in psychology and sociology. He is a co-vice president of UR Mentoring Network, he is a part of the Dean’s Student Advisory Board, and during the 2017-2018 academic year he was an appointed student representative of the Presidential Advisory Committee for Sexual Violence Prevention and Response. Additionally, he has been inducted into numerous honor societies including Omicron Delta Kappa, Mortar Board, Alpha Kappa Delta, and Psi Chi. He joined the Race & Racism Project in the summer of 2018 as a part of Team Oral History and hopes to remain an active contributor and collaborator into and through the 2018-2019 school year.

On June 16, the Saturday before Juneteenth, I had the privilege of visiting Monticello—the former home of the “Father of the Declaration of Independence” and the United States’ 3rd president, Thomas Jefferson. For those who don’t know, Juneteenth is the oldest known celebration commemorating the end of slavery in the United States. June 19, 1865 was the day that word finally spread to the Deep South of Galveston, Texas by way of Union soldiers that the enslaved were finally free—even though this was two and a half years after Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation (Jan. 1, 1863). Author of one of the most well-known lines in all of United States history, “We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men are created equal…” Jefferson himself was responsible for the enslavement of hundreds of people during his lifetime.

On June 16, the Saturday before Juneteenth, I had the privilege of visiting Monticello—the former home of the “Father of the Declaration of Independence” and the United States’ 3rd president, Thomas Jefferson. For those who don’t know, Juneteenth is the oldest known celebration commemorating the end of slavery in the United States. June 19, 1865 was the day that word finally spread to the Deep South of Galveston, Texas by way of Union soldiers that the enslaved were finally free—even though this was two and a half years after Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation (Jan. 1, 1863). Author of one of the most well-known lines in all of United States history, “We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men are created equal…” Jefferson himself was responsible for the enslavement of hundreds of people during his lifetime.

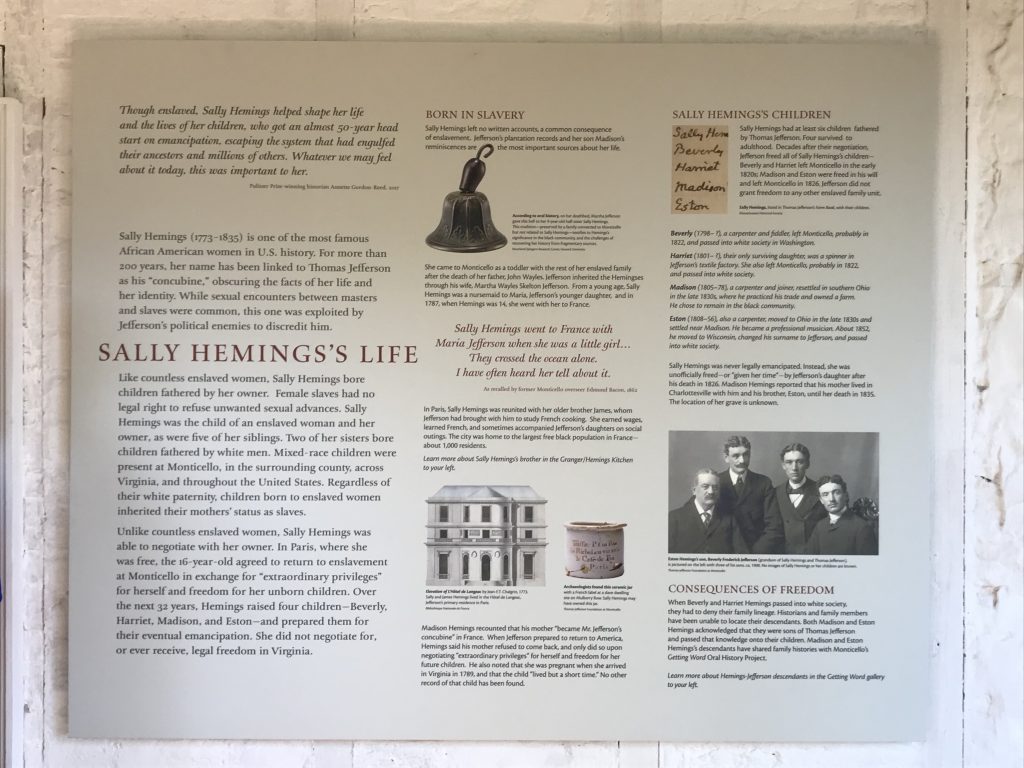

The particular Saturday I visited Monticello, the day was centered around a program entitled “Look Closer.” The day included a public family reunion of Jefferson’s descendants—black, white, and mixed—as well as the opening day of a new Sally Hemings exhibit. Per the program’s brochure, on this day “Monticello conclude[d] the Mountaintop Project, a major restoration initiative made possible by We Hold These Truths: The Campaign for Monticello.”. This project led to the restoration of previously down trodden areas and neglected exhibits (particularly involving the histories of the enslaved people of Monticello) as well as to the creation of a new exhibit, “The Life of Sally Hemings,” the mother of four of Jefferson’s formerly enslaved children. Half-sister to Jefferson’s wife, Martha Wayles Skelton Jefferson, Sally Hemings was only 25% black herself as her mother was the offspring of an enslaved woman forced to birth the child of her master. But as the law had it, she was black, born enslaved and therefore her children would be enslaved as well. The exhibit itself was located in the South Wing of the grounds, in a small room that can only accommodate 10 or so visitors at a time. Aside from the info-panels outside just before entering, the entire exhibit was a 5-minute, mini-documentary that takes you through the main events and details of Sally Hemings’ life.

The particular Saturday I visited Monticello, the day was centered around a program entitled “Look Closer.” The day included a public family reunion of Jefferson’s descendants—black, white, and mixed—as well as the opening day of a new Sally Hemings exhibit. Per the program’s brochure, on this day “Monticello conclude[d] the Mountaintop Project, a major restoration initiative made possible by We Hold These Truths: The Campaign for Monticello.”. This project led to the restoration of previously down trodden areas and neglected exhibits (particularly involving the histories of the enslaved people of Monticello) as well as to the creation of a new exhibit, “The Life of Sally Hemings,” the mother of four of Jefferson’s formerly enslaved children. Half-sister to Jefferson’s wife, Martha Wayles Skelton Jefferson, Sally Hemings was only 25% black herself as her mother was the offspring of an enslaved woman forced to birth the child of her master. But as the law had it, she was black, born enslaved and therefore her children would be enslaved as well. The exhibit itself was located in the South Wing of the grounds, in a small room that can only accommodate 10 or so visitors at a time. Aside from the info-panels outside just before entering, the entire exhibit was a 5-minute, mini-documentary that takes you through the main events and details of Sally Hemings’ life.

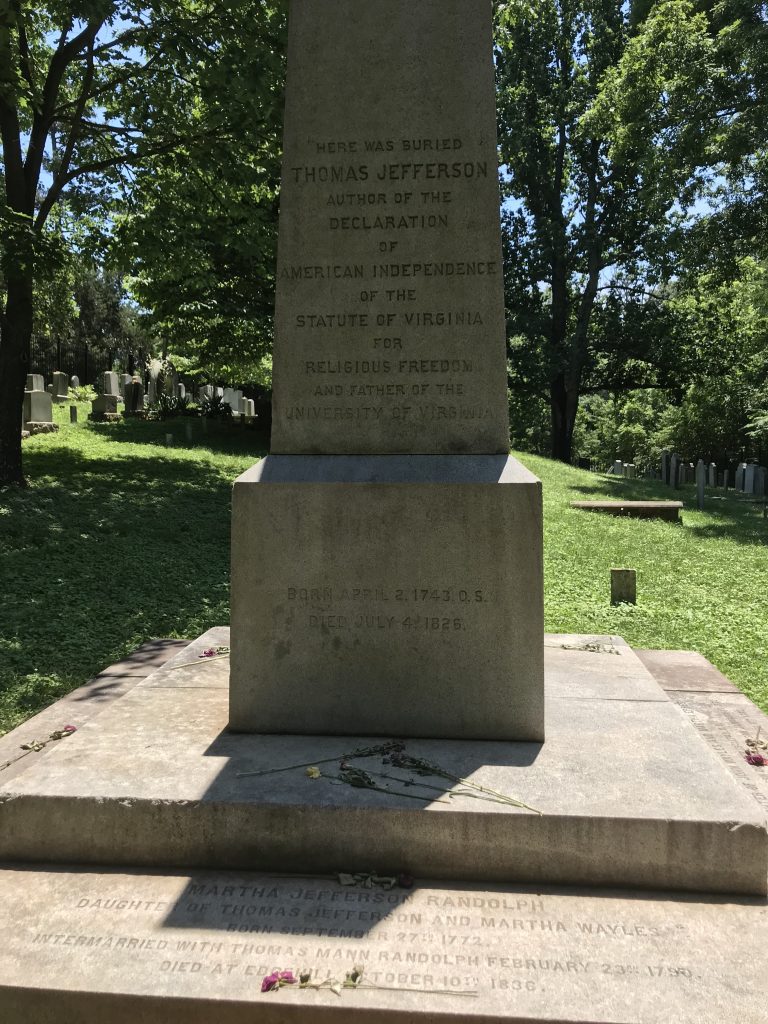

In addition to the fact that she was mother to four of Jefferson’s children, what has also helped bolster her remembrance is that she negotiated her children’s freedom. Prior to returning to the United States from her trip to France with Maria Jefferson, Hemings made Jefferson agree to free her yet-to-be-born children when he died, or else she would not return from France (where she was free). And it worked. In 1826 when Jefferson died, Hemings’ children were freed through his will, but Sally herself never negotiated her own freedom. Jefferson went on to be buried in the family—and when I say family, I mean white family—graveyard.

This family graveyard is protected by a freshly painted, black with gold spear-tipped, iron fence. The front gate holds a gold crest labeled “TJ”, and just behind these gates lies Thomas Jefferson’s obelisk surrounded by his white children and his wife. The front face of the obelisk reads “Here was buried Thomas Jefferson/Author of the Declaration of American Independence/of the Statute of Virginia for Religious Freedom/and Father of the University of Virginia.” Throughout the graveyard you will find properly labeled and maintained headstones, pedestals, and even above ground chest tombs. This graveyard is owned and maintained by the Monticello Association, “An organization of Jefferson’s lineal descendants,” per the bronze placard outside the fences that even provides a map and key of who is buried where on the front portion of the site. Initially I was impressed by the appearance and maintenance of the graveyard, but on my walk back up the hill of Mulberry Row to the big house, I came across an ongoing Slavery Tour of the plantation. And I was thankful I did.

This family graveyard is protected by a freshly painted, black with gold spear-tipped, iron fence. The front gate holds a gold crest labeled “TJ”, and just behind these gates lies Thomas Jefferson’s obelisk surrounded by his white children and his wife. The front face of the obelisk reads “Here was buried Thomas Jefferson/Author of the Declaration of American Independence/of the Statute of Virginia for Religious Freedom/and Father of the University of Virginia.” Throughout the graveyard you will find properly labeled and maintained headstones, pedestals, and even above ground chest tombs. This graveyard is owned and maintained by the Monticello Association, “An organization of Jefferson’s lineal descendants,” per the bronze placard outside the fences that even provides a map and key of who is buried where on the front portion of the site. Initially I was impressed by the appearance and maintenance of the graveyard, but on my walk back up the hill of Mulberry Row to the big house, I came across an ongoing Slavery Tour of the plantation. And I was thankful I did.

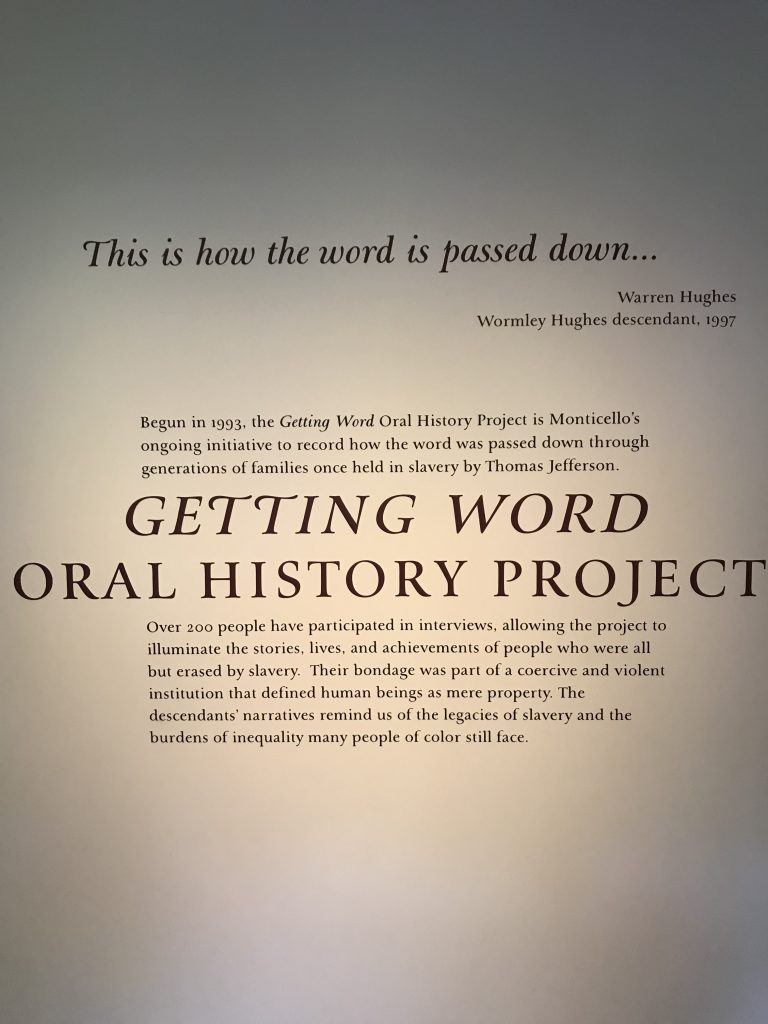

While on the tour, I heard the deeper stories of notable enslaved persons that I, as well as thousands of visitors, would not have known or understood by simply reading the pre-established panels along Mulberry Row. And if a more complete history of Monticello and its history of slavery peaks your interests, I suggest looking into the Fossett, Gillette, Hern, and the Coleman-Henderson-Shelton families. All of these are former enslaved family lines whose presence during the time of enslavement was crucial to the Monticello operation, and today is still crucial as their descendants have been part of the ongoing “Getting Word” Oral History Project—“Monticello’s ongoing initiative to record how the word was passed down through generations of families once held in slavery by Thomas Jefferson.” But at the conclusion of the tour, while I was thankful to have been educated, I was puzzled. Where was or is the enslaved people’s burial ground?

While on the tour, I heard the deeper stories of notable enslaved persons that I, as well as thousands of visitors, would not have known or understood by simply reading the pre-established panels along Mulberry Row. And if a more complete history of Monticello and its history of slavery peaks your interests, I suggest looking into the Fossett, Gillette, Hern, and the Coleman-Henderson-Shelton families. All of these are former enslaved family lines whose presence during the time of enslavement was crucial to the Monticello operation, and today is still crucial as their descendants have been part of the ongoing “Getting Word” Oral History Project—“Monticello’s ongoing initiative to record how the word was passed down through generations of families once held in slavery by Thomas Jefferson.” But at the conclusion of the tour, while I was thankful to have been educated, I was puzzled. Where was or is the enslaved people’s burial ground?

As I concluded my visit, my quest became to find this plot of land. I had enjoyed the day thus far and all that I had witnessed (e.g. a well done Q&A panel and wonderful musical performances) and learned (too much to list), but my visit felt incomplete without having seen the African American burial ground.

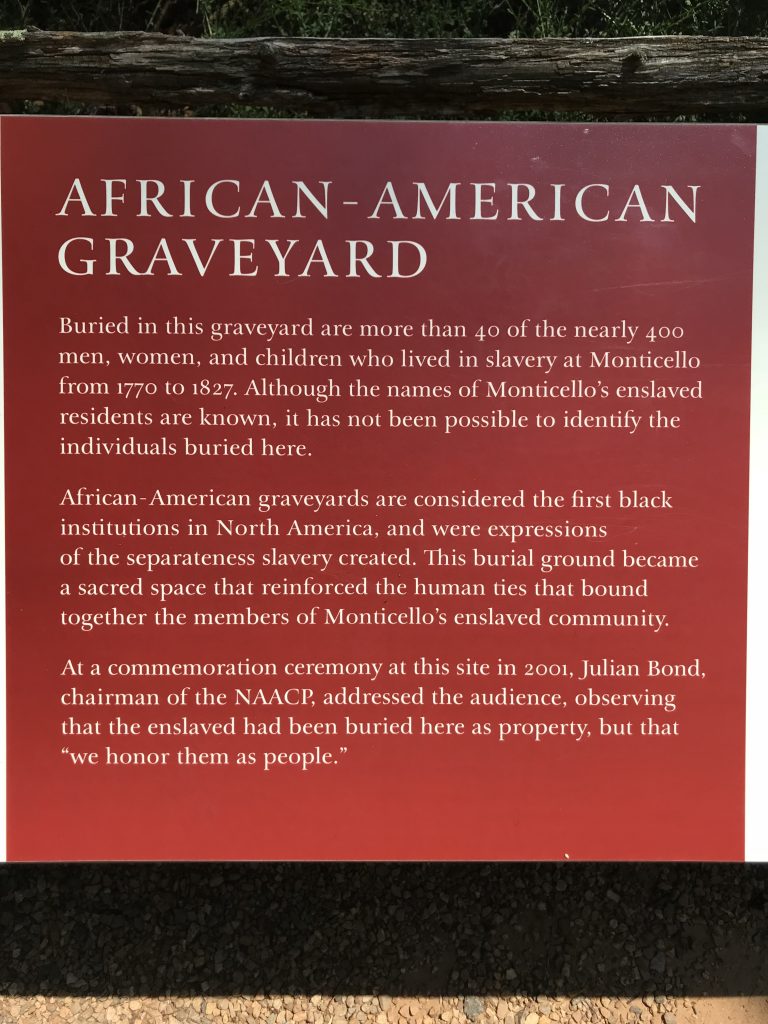

Like I said I was puzzled, almost annoyed as to why the African-American Burial Ground was located down the mountain, past the modern day visitor’s center, and behind the bus parking lot, with little signage that might direct you to it… Once I made it there I was not surprised to find zero headstones, tombs, or monuments. There is no iron fence, but instead a low-bearing wooden one. There is a list of known enslaved people who died on the site of Monticello and an explanation of potential burial spots where particular depressions in the dirt lay. In 2001, the NAACP held a commemoration ceremony for those who were buried as property, but whom “we [now] honor as people,” as quoted by Julian Bond (chairman of the NAACP). I am not ignorant to the fact that it was commonplace in the South to leave African American burial grounds unmarked and unattended to. However, for as much attention that was put into the updated exhibits and celebration on the mountaintop portion of Monticello, I wish that at least a small portion of the effort shown there could have been used to tell the story of the near 400 forgotten people who once walked these same grounds.

Like I said I was puzzled, almost annoyed as to why the African-American Burial Ground was located down the mountain, past the modern day visitor’s center, and behind the bus parking lot, with little signage that might direct you to it… Once I made it there I was not surprised to find zero headstones, tombs, or monuments. There is no iron fence, but instead a low-bearing wooden one. There is a list of known enslaved people who died on the site of Monticello and an explanation of potential burial spots where particular depressions in the dirt lay. In 2001, the NAACP held a commemoration ceremony for those who were buried as property, but whom “we [now] honor as people,” as quoted by Julian Bond (chairman of the NAACP). I am not ignorant to the fact that it was commonplace in the South to leave African American burial grounds unmarked and unattended to. However, for as much attention that was put into the updated exhibits and celebration on the mountaintop portion of Monticello, I wish that at least a small portion of the effort shown there could have been used to tell the story of the near 400 forgotten people who once walked these same grounds.

This is a critique of Monticello and their curation (or lack thereof) and lack of attention to the African American burial site only. In many ways, and likely still more to come, Monticello has done exceptionally well in paying and showing respect to the enslaved and their descendants as is evident on the mountaintop. Indeed I look forward to the future exhibits, programs, and events that will focus on the enslaved people of Monticello, as I am confident this will continue to be a focal point of the plantation as a historic tourist attraction and education destination. Understandably, they began telling the stories of people whose stories were most immediately accessible, and to this I have no objections. Quite simply, my hope is that for those who never made it off the plantation, for those who were buried without a care of recollection and remembrance, my hope is that their stories have not been and will not be forgotten. One day I hope to return to Monticello with children of my own and be able to explain to them how history can only be taught and learned if it is first remembered. And, more importantly, if you are going to learn history, it is best to learn the entire story. I suppose that’s why you, the reader, are here on this site. May you never stop learning and always tell the whole story to the best of your ability.

Great stuff! Looking forward to more of your posts.