by Mysia Perry

Mysia Perry is a rising sophomore from Richmond, VA with an intended major in Leadership Studies and minor in Sociology and Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies. She is a part of the WILL* program, Peer Advisors and Mentors, Planned Parenthood Generation Action, and she is both an Oldham and Oliver Hill Scholar. This is her first summer working on the Race & Racism Project on Team Oral History, and she is very excited to begin working for more equitable environment here at the University of Richmond.

I am always excited and proud to pass the bronze statue on Broad Street and Adams Street in Richmond, Virginia. Maggie Lena Walker’s statue stands at 10-feet, surrounded by the events that led her to be the respected, powerful businesswoman we know her as today. Other feelings consume me when I travel through the Monument Avenue Historic District: disappointment and discomfort. Those statues tower over my car, with the largest totaling over 60 feet tall. Those statues celebrate the enslavement of my ancestors.

I am always excited and proud to pass the bronze statue on Broad Street and Adams Street in Richmond, Virginia. Maggie Lena Walker’s statue stands at 10-feet, surrounded by the events that led her to be the respected, powerful businesswoman we know her as today. Other feelings consume me when I travel through the Monument Avenue Historic District: disappointment and discomfort. Those statues tower over my car, with the largest totaling over 60 feet tall. Those statues celebrate the enslavement of my ancestors.

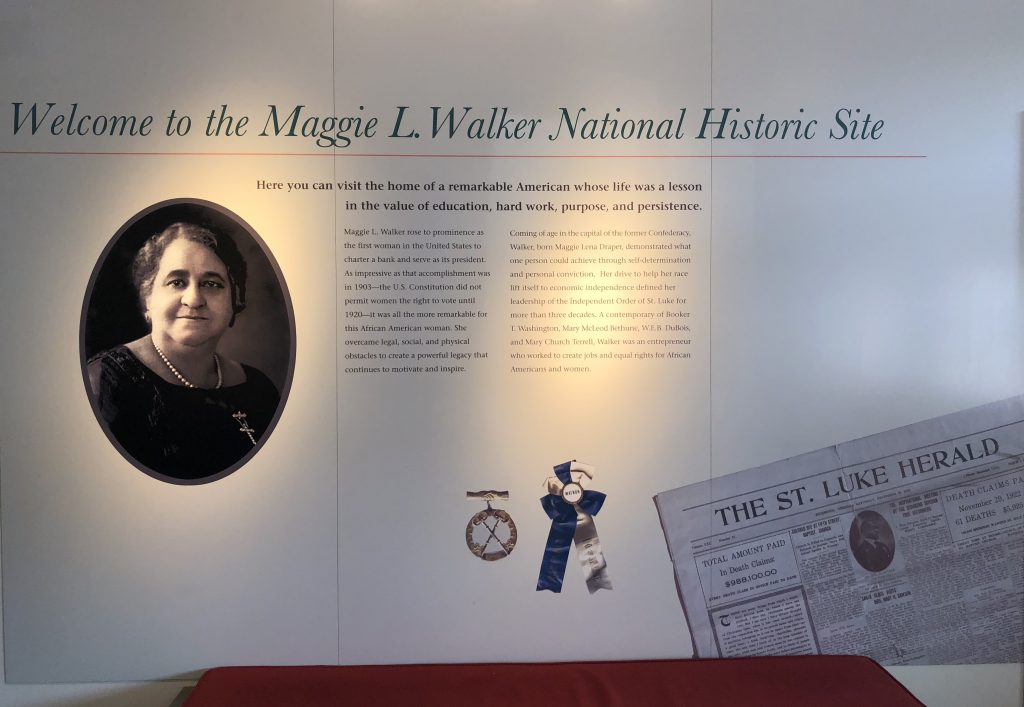

When others think of Richmond, it is hard not to concentrate on our city weighing the decision of what to do with the Confederate statues on Monument Avenue. Our identity has been consumed by this, especially after the events of last August in Charlottesville regarding the fate of other Confederate monuments. It is easy to forget about some of the opportunities Richmond held for black people during the Jim Crow era. I found that as I visited the Maggie L. Walker Historic Site in Jackson Ward, I was able to finally see more than Richmond’s connection to the Civil War.

As my family and I entered the visitor center on North 2nd Street, we were greeted by park rangers who welcomed us inside and gave us some basic information about how their tours work. It was then that we were able to explore the gift shop while we waited for the short film on Maggie Walker and tour of her home to begin. I was grateful to see that almost all of the books and items were commemorating the civil rights movement, building community throughout our state, and many historical black figures, but was disappointed in the size altogether. I knew the historic site would be smaller because of the limitation to the size of her, though rather large, house.

As my family and I entered the visitor center on North 2nd Street, we were greeted by park rangers who welcomed us inside and gave us some basic information about how their tours work. It was then that we were able to explore the gift shop while we waited for the short film on Maggie Walker and tour of her home to begin. I was grateful to see that almost all of the books and items were commemorating the civil rights movement, building community throughout our state, and many historical black figures, but was disappointed in the size altogether. I knew the historic site would be smaller because of the limitation to the size of her, though rather large, house.

I found that I was also interested in seeing the spaces involved in her other accolades, specifically as the first female bank president of any race to charter a US bank. Maggie Walker was a well-established black woman who lead her people to create a prosperous area for themselves in a time when black people were not allowed to eat, learn, or work in places based solely on their race. There was no space dedicated to her work at the Consolidated Bank and Trust Company, where she worked until her death after merging St. Luke Penny Savings Bank with two other banks in Richmond. The space lacked any formal or written information throughout the house for those who may not have the time to take out of their day for a guide-led tour. Your knowledge of Maggie Walker and her work was almost strictly limited to what information is shared by a tour guide.

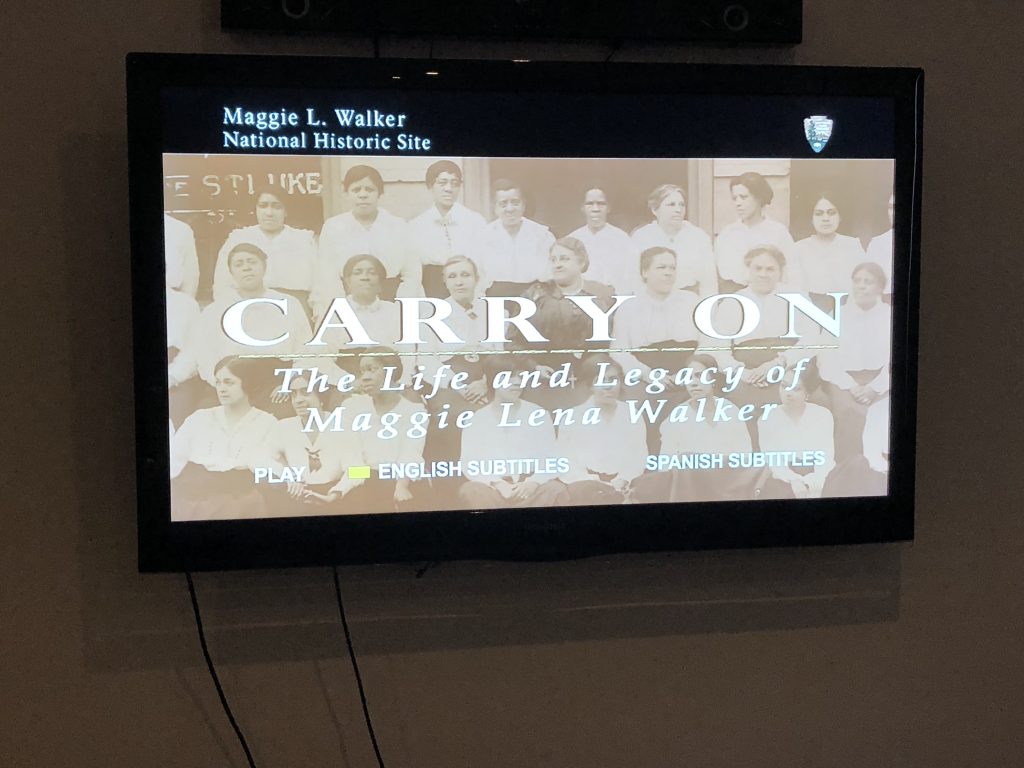

When the time came, the short documentary began and we were given a 20-minute summary of the many accomplishments of Maggie L. Walker. We were informed about her influence on the community and the leadership roles she held in the movement of black women working in nontraditional positions here in the city. We learned how the neighborhood she played a major role in, Jackson Ward, had almost 80 major black business in the Jim Crow era, when black spaces were few and far between. Maggie Lena Walker was known for her strong belief in supporting our own people. The short film quoted her saying, “The only way to kill the lion of racism was to stop feeding it.” With her leadership, she was able to create a successful and the longest lasting black bank, the Consolidated Bank and Trust, after the stock market crash of 1929.

When the time came, the short documentary began and we were given a 20-minute summary of the many accomplishments of Maggie L. Walker. We were informed about her influence on the community and the leadership roles she held in the movement of black women working in nontraditional positions here in the city. We learned how the neighborhood she played a major role in, Jackson Ward, had almost 80 major black business in the Jim Crow era, when black spaces were few and far between. Maggie Lena Walker was known for her strong belief in supporting our own people. The short film quoted her saying, “The only way to kill the lion of racism was to stop feeding it.” With her leadership, she was able to create a successful and the longest lasting black bank, the Consolidated Bank and Trust, after the stock market crash of 1929.

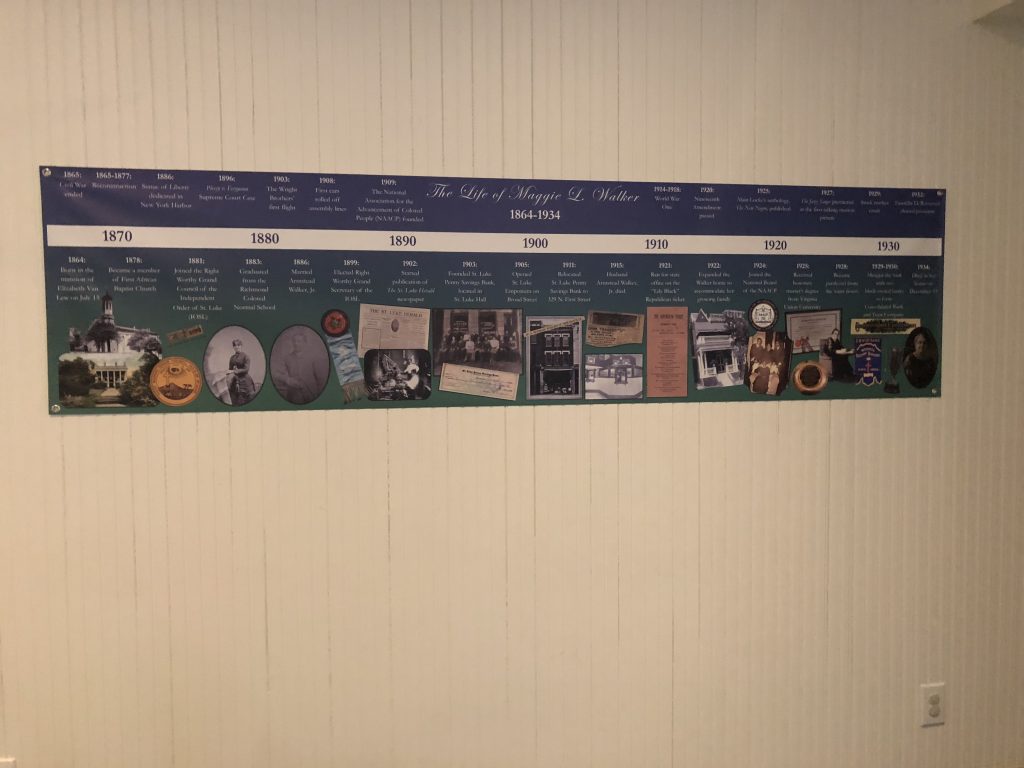

The film and tour of the Maggie L. Walker House worked well to incorporate the life of Walker, her family, her friends, and her community. We were able to learn of the tragedies of her life and the successes. Maggie Walker lost her husband, Armistead, in a tragic accident. Her eldest son shot Mr. Walker after mistaking him for an intruder. The son, Russell, then died at 32 years old after battling with depression and alcoholism. Despite this, Walker went on to be a determined woman who worked to better her community and lead women to accomplish more than what was expected of us, until she died of complications from diabetes in 1934. She worked to found and/or lead organizations in her area that promoted community among black people, like the Right Worthy Grand Council of the Independent Order of St. Luke and the National Board of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). I was pleasantly surprised by how well the site explained her story in the context of the events of the world around her, like the First World War, the stories of other civil rights activists, like W. E. B. Du Bois, and the NAACP being founded.

The film and tour of the Maggie L. Walker House worked well to incorporate the life of Walker, her family, her friends, and her community. We were able to learn of the tragedies of her life and the successes. Maggie Walker lost her husband, Armistead, in a tragic accident. Her eldest son shot Mr. Walker after mistaking him for an intruder. The son, Russell, then died at 32 years old after battling with depression and alcoholism. Despite this, Walker went on to be a determined woman who worked to better her community and lead women to accomplish more than what was expected of us, until she died of complications from diabetes in 1934. She worked to found and/or lead organizations in her area that promoted community among black people, like the Right Worthy Grand Council of the Independent Order of St. Luke and the National Board of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). I was pleasantly surprised by how well the site explained her story in the context of the events of the world around her, like the First World War, the stories of other civil rights activists, like W. E. B. Du Bois, and the NAACP being founded.

I found that my main concern was the size. Because it is a house, there are limitations on the number of people that can occupy the space at once. Large schools wouldn’t be able to visit at one time and tourists may find it hard to locate. Unlike many other monuments that have large signage or markers, the Maggie L. Walker Historic Site lacked in that department. My mom has lived in Richmond more than half of her life and still needed directions to get there.

This was not my first time to the Walker house. Unfortunately I feel that because there was less signage and written information, young Mysia found it easy to forget Maggie L. Walker’s story. Before my most recent visit, I could tell you very little about who she was. Now, I amazed that I did not know more. I want to know more. But I worry that because of these things, Maggie L. Walker’s home and history will forever remain a hidden gem, deep in the former capital of the Confederacy.

This was not my first time to the Walker house. Unfortunately I feel that because there was less signage and written information, young Mysia found it easy to forget Maggie L. Walker’s story. Before my most recent visit, I could tell you very little about who she was. Now, I amazed that I did not know more. I want to know more. But I worry that because of these things, Maggie L. Walker’s home and history will forever remain a hidden gem, deep in the former capital of the Confederacy.