by Cory Schutter

Cory Schutter is a junior from Midlothian, Virginia. He is double majoring in Rhetoric and Communication Studies and Women, Gender and Sexuality Studies. He is a Bonner Scholar, a Center for Civic Engagement Ambassador, and a Student Coordinator at UR Downtown. He began his involvement with the Race & Racism Project in the summer of 2017, as an A&S Summer Fellow. This post was written as a part of Digital Memory & the Archive, a course offered in Fall 2017.

On February 23, 1984, Collegian staff writer Ginny Yoder broke a story on sexual harassment plaguing the University of Richmond: “Obscene: Women get phone calls.” Residents in the Westhampton College dorms and University Forest Apartments had begun to receive obscene phone calls from unidentified callers. An epidemic of sexual harassment began spread from phone to phone around Westhampton College.

On February 23, 1984, Collegian staff writer Ginny Yoder broke a story on sexual harassment plaguing the University of Richmond: “Obscene: Women get phone calls.” Residents in the Westhampton College dorms and University Forest Apartments had begun to receive obscene phone calls from unidentified callers. An epidemic of sexual harassment began spread from phone to phone around Westhampton College.

“It’s traumatic for the girls,” Campus Police Chief Robert C. Dillard told the Collegian. This trauma would haunt Westhampton College as obscene phone calls continued into the early 1990s.

In an era of smartphones and caller ID, it’s hard for me to imagine a rash of obscene phone calls spreading across campus. In this age, I can expect to be protected by law should I receive sexual harassment — Title IX is only one phone call or email away.

In 1980, Alexander v. Yale established that sexual harassment was illegal, as it was a form of sex discrimination covered by Title IX. Under Dr. E. Bruce Heilman’s administration, Title IX policies began to be implemented on campus. In 1985, Provost Zeddie Bowen discovered that a written policy against sexual harassment did not exist for the university. Despite the rash of obscene phone calls, the provost assured The Collegian that there was “no indication that there is a problem on this campus.”

Despite these policies, there is no indication of a Title IX investigation or intervention in regard to the widespread sexual harassment that Westhampton College experienced. The situation continued to worsen. In 1987, the Collegian sampled a phone call from a sexual harasser. Staff writer Jennifer Komosa describes listening to a low and drunken voice, speaking these chilling words: “I know you’re there and I am coming to get you. I am going to kill you . . . You are going to be sorry for what you did.”

There’s another factor which complicates this narrative: the identities of the two callers. Yoder’s 1984 article mentions that there are two different callers — both male, one white, one black. “Most of the calls have been from a white male with a Southern accent,” the article states, describing this man as using obscene and threatening language. This caller would often use intimidation in his harassment — suggesting that he had been watching the harassment victims all night long.

“The other caller is a black male who uses vulgar, straight obscenity,” Yoder wrote. In a 2006 article, Patricia Rice of Washington University in St. Louis, describes this identification as a form of “linguistic profiling.” Identifying race from a phone call is a form of stereotyping, one which the University of Richmond Police Department apparently engaged in.

In 1990, tension increased as explicit descriptions of the sexual harassment were published in the Collegian. Pamela Orsi received calls from someone she described as a “faggy guy” at 7:30am. Candace Blydenburgh received a phone call at 7:45am from a man who wanted to know her bra size. A freshman received a call with an invitation from a man to “see his 12-inch-long —-.” To discourage the phone calls, the freshman claimed she “was a lesbian and not interested.”

In the words of Jarret M. Drake, “The implicit function of liberal arts colleges may be to replicate systems and structures of social inequality and exclusion.” The sexual harassment forced through phone lines was doubly forced by the University itself as it took a casual approach to a serious problem. The collective social memory of the University of Richmond does not appear to designate a space where this psychic violence can come to rest. Perhaps the action of remembering these events comes across as obscene. Problematizing this narrative requires a condemnation of police authority, thus implicating the college in wrongdoing.

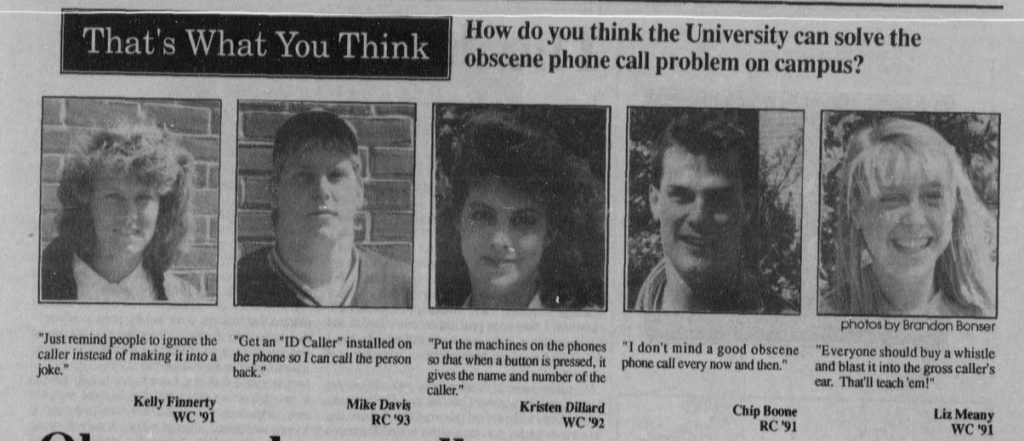

A 1990 “That’s What You Think” column polled students for solutions to the obscene phone call crisis. Chip Boone, a senior, seemed to take the matter lightly, perhaps indicative of how the crisis was being handled: “I don’t mind a good obscene phone call every now and then.”

Unlike Chip Boone, most victims of gender violence cannot wipe away their trauma or find ways to enjoy it. Recognizing the intersectionality between gender violence and trauma is crucial to create a space for memory. “Getting an obscene phone call can be as traumatic as being hit,” O’Toole and Schiffman write, describing how agency is stolen from a woman who receives an obscene or threatening phone call. The University’s reaction of telling victims to solve their own problems made victims bear the responsibility for their lack of agency.

The epidemic extended for over 6 years. In these articles and during this passage of time, there seems to be a dissonance. Students were encouraged to troubleshoot and resolve problems themselves. The campus police made repeated suggestions as to how to react to phone calls, but never came up with a solution to prevent the calls in the first place. The problem appears to have been minimized.

In September of 1991, the epidemic ended as quickly as it started. The Collegian announced that the days of unknown callers were over, welcoming in Last Call Return, or Star 69.