The Philadelphia History Museum is a two-level city history museum, claiming to be “your gateway into Philadelphia’s past!”. It has a daunting task before it: telling the history of the city of Philadelphia. The museum uses its exhibits to proudly show us where the city has been and question where it will go. Though its story was one of Philadelphian pride, the museum did not shy away from acknowledging tensions, such as those between races and citizens and government. The exhibit on preserving historic sites in Philadelphia, “Saved! Preserving Old Philadelphia: 85 Years of The Philadelphia Society for the Preservation of Landmarks,” used unique storytelling and interactive methods to describe the challenges in preserving Philadelphia’s history.

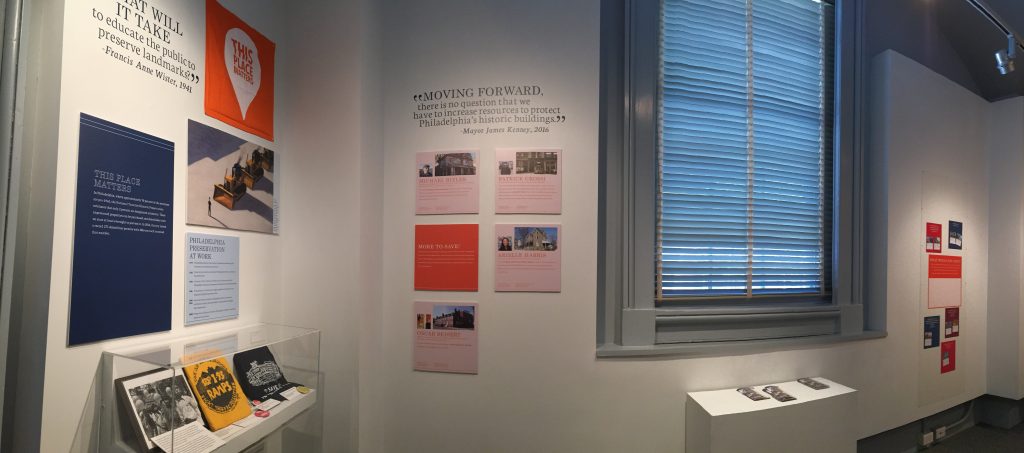

The exhibit is housed in a small, square room; I was actually surprised by how small it was. Compared to other exhibits I have seen at different museums, this was like a closet. However, the exhibit designer utilized the space, grouping information on the wall by themes: an overview of the history of preserving sites in Philadelphia, the modern-day preservationist movement, the twentieth century preservation movement, and Society Hill and urban renewal. According to the plaque “This Place Matters,” roughly 70% of buildings in Philadelphia were built before 1945, but only 2% of these are designated as historic; in 2014, the city issued 275 demolition permits. The exhibit was guided by a question by Francis Anne Wister that was presented on the wall: “What will it take to educate the public to preserve landmarks?” In the exhibit, there were interactive sections, such as a table with playing cards and instructions for games like “Snap” and “I Doubt It”—women used to hold teas and card games to raise money to preserve the Powel House—and a magnetic part of the wall where patrons could look at eight magnets, each one with a picture and description of a historic site at risk of destruction, and could move a magnet to the middle of the wall to “save” it.

The exhibit is housed in a small, square room; I was actually surprised by how small it was. Compared to other exhibits I have seen at different museums, this was like a closet. However, the exhibit designer utilized the space, grouping information on the wall by themes: an overview of the history of preserving sites in Philadelphia, the modern-day preservationist movement, the twentieth century preservation movement, and Society Hill and urban renewal. According to the plaque “This Place Matters,” roughly 70% of buildings in Philadelphia were built before 1945, but only 2% of these are designated as historic; in 2014, the city issued 275 demolition permits. The exhibit was guided by a question by Francis Anne Wister that was presented on the wall: “What will it take to educate the public to preserve landmarks?” In the exhibit, there were interactive sections, such as a table with playing cards and instructions for games like “Snap” and “I Doubt It”—women used to hold teas and card games to raise money to preserve the Powel House—and a magnetic part of the wall where patrons could look at eight magnets, each one with a picture and description of a historic site at risk of destruction, and could move a magnet to the middle of the wall to “save” it.

The last section of the exhibit discussed urban renewal, specifically in Old Philadelphia and Society Hill. The museum described Old Philadelphia as “the city’s earliest settlement” and having a “vibrant history of immigration, preservation, and 20th and 21st century urban renewal.” It was redlined in 1934, which meant that immigrants and people of color could not obtain mortgages or insurance. Society Hill was a predominantly Russian Jewish and African American neighborhood and was described by W.E.B. DuBois as the “worst slum in the city.” Now Society Hill consists of high-end housing as a result of urban renewal from the Federal Housing Act of 1954. However, the original residents had to sell their properties at a loss or rehabilitate them at a great expense.

I applaud the museum on addressing the issue, though they did not offer much critique on the matter. Much like the researchers on this project, the museum chose to remain objective but still shed a light on the detrimental outcomes of urban renewal and challenge the current identity of Society Hill. However, they do not offer many details into the conflict that must have arose between the original residents and the federal government, but we know it must have happened.

This is the one problem I had with the exhibit: they presented these different preservation movements and even included movements that involved tensions between the government and racial minorities, such as Society Hill and Chinatown. They acknowledge that these conflicts happened, but do not push further and explain why they happened, which is a part of history and an important part of the narrative. However, this could be because the museum wanted to focus more on the overall preservation movement and maintain the narrative of Philadelphian pride and success; however, this means that some stories, though highlighted, are still left hidden. In addition, the exhibit seems to convey that these stories are not as important as the stories of white preservationists and sites that belonged to prominent, white historical figures: there is a whole wall dedicated to the how Frances Anne Wister and The Philadelphia Society for the Preservation of Landmarks (PhilaLandmarks) preserved the Powel House, where the mayor of Philadelphia Samuel Powel had lived with his wife Elizabeth who was a close confidant of George Washington.

As the title “Saved!” suggests, the exhibit praises the work that activists have done to preserve certain parts of the city and that they were successful in doing so. However, the exhibit also acknowledges that there is still a lot of work to be done and that preservationists, past and present, faced a lot of challenges, especially with the government. Though it presented conflicts between racial minorities and the government, such as urban renewal, it did not offer as much detail on these issues, perhaps in an attempt to maintain the narrative of Philadelphian pride. This offers some benefits, such as presenting the hardships that racial minorities faced and challenging the current identity of Philadelphia’s landmarks. It presents drawbacks as well, especially since there was more detail offered on the preservation of the Powel House, which was owned by white people, and The Philadelphia Society for the Preservation of Landmarks, which was started by rich, white women. Much like our research, this exhibit begs the question What deserves to be saved? Though it attempts to answer this question, I find its answer frustrating and a bit confusing, and I want to ask instead Why are some things not saved?

Karissa Lim is a rising senior at the University of Richmond double majoring in Psychology and Rhetoric & Communication Studies. She worked with the Race and Racism at UR Project during the Fall 2016 semester in the class Digital Memory and the Archive. She is working on the project again during Summer 2017 as a correspondent in Philadelphia, PA.