by Cory Schutter

On the tinted glass doors of the museum are three words: Confederacy. Union. Freedom.

These words frame a visit to the Museum of the Confederacy — three complicated, tense, load-bearing words. They frame the Civil War as an idealistic fight for freedom, and I wonder about the truth in this. When we talk about freedom, to whose freedom do we refer?

During my visit to the Museum of the Confederacy, I kept these three words in mind. I began my journey through the main exhibition floor, and was quickly attracted to a colorless panel.

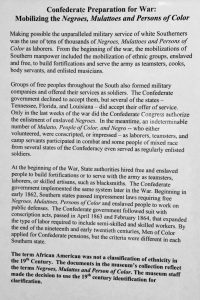

The panel is titled “Confederate Preparation for War: Mobilizing the Negroes, Mulattoes and Persons of Color.” There’s a note at the bottom of the panel that explains that the museum staff decided to use the italicized terms “Negroes, Mulattos and Person of Color… for clarification.”

What did it mean to keep the original racial terminology? I wondered why this racial terminology was being used when no primary sources were sampled. Why were there grammatical discrepancies in the panel? How did this reflect on the importance of the panel?

I’m drawn in by the panel’s title, initially interested by the lack of serial comma, and then I begin to notice how the way the word ‘the’ seems to position humans as tools. Was this intentional?

“From the beginning of the war, the mobilizations of Southern manpower included the mobilization of ethnic groups, enslaved and free, to build fortifications and serve the army as teamsters, cooks, body servants, and enlisted musicians.”

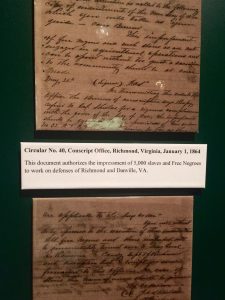

I wish there was a better way to envision what this would look like, and what it meant for non-whites serving in the Confederate States Army. A corresponding panel displays a circular that impressed “5,000 slaves and Free Negroes to work on the defenses of Richmond and Danville, VA.” As far as I could find, these two panels are the only documentation in the museum related to the Confederate mobilization of people of color.

In this context, I have to wonder what the purpose of this exhibit was. It stands out in the museum, deviating from a normative narrative of the Civil War where white soldiers fought over the fate of an enslaved population. How much more complex does the war become when the enslaved fight as proxies for their captors?

Offering a further complication, “Groups of free peoples throughout the South also formed military companies and offered their services as soldiers.” These offers of service were accepted by the states of Tennessee, Florida, and Louisiana, and in the last weeks of the war, the Confederate Congress authorized “the enlistment of enslaved Negroes.” I have to wonder, what motivated these individuals to fight? What cause did they identify with?

I’m curious if there’s a way to reinterpret this exhibit to bring light to the marginalized peoples within it. How can we complicate this ‘Confederacy. Union. Freedom.’ narrative? When a museum offers little information on a particular subject — or keeps additional information in archives and out of public sight — what histories are told and untold?

Undoubtedly, there is a lack of memorialization in this space for the people of color who came to find themselves fighting in the Civil War. While lending a brief moment of visibility to who fought in the war, the panel refuses to engage in a debate surrounding this complicated subject. What does this lack of visibility mean for a population who volunteered, or were pressed or coerced, into the war effort?

The lack of details, the peculiar grammar, the lack of representation in the museum: these unusual characteristics in a narrative concern me. Perhaps this gap-ridden form of memorialization serves to ease pain, or helps tidy away the messy contradictions of reality. A truncated mantra of ‘Confederacy. Union. Freedom.’ fails to answer my questions.

“In the meantime, an indeterminable number of Mulatto, People of Color, and Negro [sic] — who either volunteered, were conscripted or impressed — as laborers, teamsters, and camp servants participated in combat and some people of mixed race from several states of the Confederacy even served as regularly enlisted soldiers.”

This indeterminable number deserve answers and a narrative of their own.

Cory Schutter is a rising junior at University of Richmond, a double major in Rhetoric and Communication Studies and Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies. He is a Bonner Scholar, a Center for Civic Engagement Ambassador, and a Student Coordinator at UR Downtown.

I am always interested in this subject. My great great grandfather was a cabinet maker during the war and was called to make cannon balls at Tredegar Iron works. After the war the freed slaves had to leave wherever they had been living and a young girl, Easter, 16 years old, walked all the way from Bowling Green to Richmond with all her belongings tied to a stick, looking for work. She happened to arrive in Richmond at the same time my great great grandfather was standing on a corner of Broad Street He approached her and asked if she knew anyone who could help him with his children as his wife was “sickly”. She said, “Take me.” And he did and she raised 2 generations of Hoopers. He later served on the Richmond City Council. I have his tool chest, which I use as a sort of coffee table today and beautiful pictures of Easter, one a tintype, who my grandmother loved dearly and often talked to me about. As a young lady my Granny fell in love with a drummer in a band, a Yankee!! he was,,,, and a real groupie she was…and she married that Yankee, my grandfather!!! and she, her husband, her 2 sisters, Easter, and her father all lived on Spring Street. I have the newspaper with the g g grandfather’s obituary, April 1900. I guess because of my Granny and Easter, I would love to hear more personal stories about that war. I expect what she told me was what her father had told her and while that would be from a Richmonder’s point of view, it would seem to be accurate. I know the horrors of slavery, an abomination. I also believe that there were many southerners who didn’t understand it but were drafted for war, as we do today, and fought and died for something they knew little about.