By Karissa Lim

Though I had ventured into Philadelphia countless times before, I had no idea where I was going. I walked up and down 19th Street, trying to find Logan Square Park and the two war memorials I wanted to see. Logan Square Park is located in Center City Philadelphia; it is a circular park surrounded by various historic sites such as the Franklin Institute and Central Library. One of Philadelphia’s major roads, the Benjamin Franklin Parkway, turns into a roundabout with Logan Square Park at its center. Flags from different countries line the sides of the parkway. Figuring that the park was a well-known site, I asked a police officer for help; however, he sent me in the wrong direction. After a moment of panic, I looked at my phone and realized my mistake. Once I turned around and walked a few blocks, the crowds thinned out and I finally found the park. My next challenge was to find two memorials: the Civil War Soldiers and Sailors Memorial and the All Wars Memorial to Colored Soldiers and Sailors. I walked around the large, circular fountain in the park, desperately searching for these two monuments. A few homeless people were laid out on park benches and a small group teens were walking around the fountain. Finally, in the distance, I spotted the white stone of the Civil War Soldiers and Sailors Memorial. With cars whizzing past on the Benjamin Franklin Parkway, I began running towards it and hoped that I would not get hit.

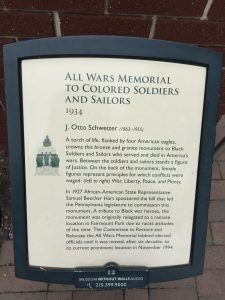

As I was running across the roundabout of the parkway, I looked to my left and saw a monument made out of dark stone. Squinting at it, I wondered if it was All Wars Memorial to Colored Soldiers and Sailors. I decided to go with my hunch and walked up to it. I was right; it was in fact the second monument I was looking for. There were no people around, so I took my time studying the monument and taking pictures. A tour bus stopped next to the monument and I feared that my quiet moment would be interrupted, but it quickly moved on. In front of the monument, a plaque explained the history and purpose of the memorial. Samuel Beecher Hart, an African-American veteran and State Representative, sponsored the bill that called for the creation of a statue to “commemorate the services of colored soldiers and sailors in various wars in which the United States has been engaged.” This monument was commissioned in 1927 and created by J. Otto Schweizer; it was completed and dedicated in 1934. Due to racist attitudes at the time, it was placed in a “remote location” in Fairmount Park, three miles north of Logan Square Park, against Schweizer’s wishes. According to the Museum Without Walls audio on the Association for Public Art’s page, the original location was partially closed off to traffic and “you practically had to be lost to find out that the memorial existed.” Hart’s descendants fought for the memorial to be moved. Eventually, in 1994, the Committee to Restore and Relocate the All Wars Memorial lobbied elected officials to move the monument to its current location on the parkway as Hart and Schweizer intended. I was stunned that it took so long for the memorial to be moved and that it was not placed there in the first place. However, I also wondered why the desired location was the Benjamin Franklin Parkway; the plaque and the Museum Without Walls audio did not give any information.

As I studied the monument, I noted that six men in six different uniforms were sculpted out of dark stone. However, when you face the memorial from the parkway, a woman symbolizing Justice is carved into the center of the monument; therefore, the eye is immediately drawn to her than to the figures around her. Small plaques placed on the sides of the memorial listed the wars that soldiers of color fought in: American Revolution, Civil War, Indian Wars, Spanish-American War, Philippine Insurrection, and World War. The inscription on the back of memorial, facing the Franklin Institute, reads: “To commemorate the heroism and sacrifice of all colored soldiers who served in the various wars engaged in by the United States of America that a lasting record shall be made of their unselfish devotion to duty as an inspiration to future generations.” Under this quote is a list of the commissioners; under the chairman, William H. Riley Jones, Hart is the first name listed.

Satisfied with the pictures and notes I had taken on the monument, I moved on to the Civil War Soldiers and Sailors Memorial. According to the Association for Public Art’s website, the memorial, which is actually two large structures on either side of the Benjamin Franklin Parkway, marks the entry to the park from the city. Initially intended to be the gates to the “Parkway Gardens,” this monument was also moved, but it was done so to accommodate the construction of the Vine Street Expressway, a major interstate between Pennsylvania and New Jersey. The Museum Without Walls audio compares the memorial and its placement at the entrance of the Benjamin Franklin Parkway to the Arc de Triomphe on the Champs-Élysées in Paris. In the audio, one of the speakers says, “They picked the Civil War because it was still such a powerful history.” At the time of its commission, the generation who had fought in the Civil War was passing away, so honoring these soldiers and sailors was an appropriate move at the time; the Museum Without Walls audio describes the monument as “heroic” and claims that the soldiers’ struggle for the preservation of the Union was “the most powerful thing that ever happened in this country by far.”

The Civil War Soldiers and Sailors Memorial has two structures because one is for soldiers and the other is for sailors. As I sprinted across the busy street, I noticed that the monument is significantly larger than the All Wars Memorial to Colored Soldiers and Sailors. In addition, it is made of white stone which not only makes it stand out but it also could lead one to assume that the figures carved into it are white men. According to the Museum Without Walls audio, the monument is a statement that the Civil War was about heroism. The figures seem to be in the middle of battle; on the back of each memorial is a list of all their battles. On the soldiers’ memorial, “Each for himself gathered up the cherished purposes of life its aims and ambitions, its dearest affections, and flung all with life itself into the scale of battle” is inscribed below the figures and “One country, one constitution, one destiny” is inscribed at the top. On the sailors’ memorial, “All who have labored today in behalf of the Union Abe wrought for the best interests of the country and the world not only for the present but for all future ages” is inscribed below the figures and “In giving freedom to the slave we assure freedom to the free,” a quote from Abraham Lincoln, is inscribed above the figures. Other than this quote, the Museum Without Walls audio speakers make note that slavery is “almost entirely absent” from the monument. In addition, they claim that only one figure on the sailors’ monument can be clearly identified as a black man. However, he is not a prominent figure on the memorial and is almost hidden behind the white sailors.

As I reflected on my visit, I thought about the critiques people have made about Monument Avenue in Richmond. Some have suggested that we need to put those monuments in context or have them in conversation with one another. How were these two monuments in Philadelphia in conversation with one another? Were they at all? The massiveness of the Civil War Sailors and Soldiers Memorial dwarfs the Colored Soldiers and Sailors Memorial; as a car speeds through the parkway, the latter could be easily missed. In addition, it is the Civil War Sailors and Soldiers Memorial that mainly features white men that is Philadelphia’s Arc de Triomphe. It seems to say then that the efforts of the white men in the Civil War are much greater than those of soldiers of color. In addition, the fact that the Civil War memorial focuses more on the preservation of the Union as its triumph furthers this point and communicates that the racial issues surrounding the war were not as important or worthy of glory. I was also surprised that a police officer sent me in the opposite direction of Logan Square Park; I assumed that due to its location on the parkway and the historic sites surrounding it that any Philadelphian, especially a police officer, would know exactly where it is. However, as I reflect on my own previous experiences in city, I have driven on the Benjamin Franklin Parkway several times before but never realized that there was a park in the middle of its roundabout or that there were even monuments nearby. When I walked up 19th Street and through Logan Square Park, it was empty and almost run-down; I could not help but contrast it to Central Park in New York City, which is so vibrant and full of life. Though Hart wanted his memorial to soldiers and sailors of color to be in a prominent location, the parkway is so busy that it is more of a passageway for cars than a place to walk around and admire. In fact, my journey to get to each memorial was extremely dangerous since I was practically running through traffic. The memorials lining the parkway are so forgotten that a tour bus did not even stop to look at or explain the Colored Soldiers and Sailors Memorial. Though we have memorialized their efforts, it seems that they are still silenced somehow. Some could argue that we should be satisfied that there is a memorial at all. However, so much of history has gone forgotten; we need to remember that all efforts made toward the war were equally important and should be remembered as such.

Karissa Lim is a rising senior at the University of Richmond double majoring in Psychology and Rhetoric & Communication Studies. She worked with the Race and Racism at UR Project during the Fall 2016 semester in the class Digital Memory and the Archive. She is working on the project again during Summer 2017 as a correspondent in Philadelphia, PA.