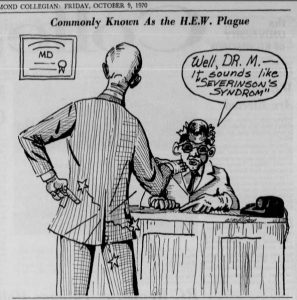

This image appeared in the October 9, 1970 edition of The Collegian, the student newspaper at the University of Richmond. The cartoon depicts Dr. George Modlin, former university president, pointing to what seems to be a pain in his backside. The doctor in the cartoon diagnoses Modlin with a fictional ailment referred to as Severinson’s Syndrome. The image caption explains that the ailment is also “commonly known as the HEW Plague.” In effect, the cartoon implies that Severinson’s Syndrome or the more commonly the HEW Plague is what’s causing the pain in Dr. Modlin’s backside.

This image appeared in the October 9, 1970 edition of The Collegian, the student newspaper at the University of Richmond. The cartoon depicts Dr. George Modlin, former university president, pointing to what seems to be a pain in his backside. The doctor in the cartoon diagnoses Modlin with a fictional ailment referred to as Severinson’s Syndrome. The image caption explains that the ailment is also “commonly known as the HEW Plague.” In effect, the cartoon implies that Severinson’s Syndrome or the more commonly the HEW Plague is what’s causing the pain in Dr. Modlin’s backside.

Severinson’s Syndrome alludes to Dr. Eloise Severinson, the regional civil rights director for the now-defunct Department of Health, Education and Welfare (HEW). Appointed to the position in 1968, Dr. Severinson was tasked with helping institutions comply with Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which prohibited discrimination on the basis of race, color, or national origin in any program receiving federal funding. In October of 1970 Dr. Severinson wrote a letter to Dr. Modlin expressing her belief that the University of Richmond still projected “an image of an exclusive all-white Southern institution.” Since the University had begun accepting federal aid several years prior, Severinson maintained that HEW could stop funding the University if it was not in compliance with the law. In the letter Severinson offered numerous solutions to the problem including the admission of more high-risk students, the hiring of black administrators, and cooperation with historically black colleges and universities in the area such as Virginia Union University. Severinson also advocated the use of more black students in the recruitment process along with an augmented interest in recruiting blacks students.

President Modlin declined to comment on the subject of the letter and instead told the Richmond Times-Dispatch that he would “take the matter up with the board of trustees later” in the month. The cartoon reflected student perception of Modlin’s lackadaisical attitude toward Severinson’s letter. His lack of comment made it seem as though the letter served as an annoyance to be ignored rather than an impassioned call to action. Further, Modlin’s complicit acceptance of the racial status quo at the University was inherently racist because it effectively shut minorities out of educational opportunities. His silence on the matter actually speaks volumes to the lack of commitment to racial equity on the part of university administrators at the time. They essentially had to be strong-armed into compliance with the Civil Rights Act and when prodded they erred on the side of inaction.