A View of the James River from Belle Isle

Looking into the water of the James River, it was hard to believe that just on the opposite bank from myself stood a city of over 200,000 people. Swirling and gurgling past my feet, the clear water of the James looked as though it had just emerged from protected lands, not like it was passing through the middle of a medium sized city. Quite fittingly, the source of the voice that narrated the audio tape that I was listening to as I gazed into the water had a lot to do with the current state of the James River. As the voice of Ralph White spoke about the ancient rocks interrupting the flow of water in front of me, I thought about the impact that his leadership would have on the James River for many years into the future. Now, as I reflect on the legacy of environmental leadership that Mr. White leaves behind, I also think about how his legacy can be preserved in the absence of a leader as strong as Mr. White. A movement towards environmental protection and stewardship can of course benefit from strong leaders, but those of us who wish to see a healthier planet for future generations cannot rely on someone leading us towards that brighter future.

Leadership, just as in any other area like business or government, is also very important in environmental protection and stewardship. Without a strong leader, a movement for greater environmentalism might loose site of its goals or suffer from a lack of a sense of direction. A leader can also help to broaden support for a movement, or drum up political or civilian monetary support for the movement. However, not everyone can be an effective leader because any strong leader needs to contain certain characteristics which will make them more effective. According to William C. Dennison and Jane E. Thomas, environmental leaders need to contain three characteristics for successful leadership: knowledge, power and passion. Knowledge refers to the leader’s understanding of environmental issues, power concerns the leader’s ability to motivate change in others through effective communication, and passion refers to the level of caring that the leader displays about environmental issues. It would of course be difficult for any one person to contain a huge amount of all three of these characteristics, but some mix of the three is necessary. According to a member of the staff of the James River Park System who works in the children education programs, passion is the most important characteristic for an environmental leader. Especially when working with children, a lesser level of knowledge is acceptable and power is also not as necessary since children are quite impressionable and easily motivated. However, it is only through passion that a leader can pass on the desire to protect our environment to children or adults. Unfortunately, adults are often more easily convinced by facts and evidence, in which case knowledge is also very important. However, for both children and adults, the ability of a leader to instill a desire to protect the environment is most important, whether through passion, knowledge, or power, and Ralph White was so effective as an environmental leader because he could convince those around him that the James River and the environment around the river were worth protecting.

Ralph White, standing in front of the James River

Ralph White, now retired from the James River Park System, is credited as the father of the park. Melissa Scott Sinclair of “Style Weekly” refers to Mr. White as “the man who shaped the rough James River Park System into a gem”. However, as Ms. Sinclair’s article points out, Mr. White did not take money and resources from the city or state government to build the park, but rather used “an army of volunteers” to the James River and surrounding property into a central feature of the city of Richmond. Mr. White built support for the park through ideal environmental leadership. Descriptions of Mr. White portray a man most certainly not lacking in passion. His training as a naturalist provided him with plenty of knowledge, and even if he did not enjoy working with the government and those who did not fully support his vision, Mr. White still had the power to motivate them to mostly support him and the park. But now that Mr. White has retired, does another leader take his place, or can his legacy be protected and even built upon without a single leader? Mr. White himself has said that the success, and even greater future for the James, is in the hands of the future James River stewards. But who are these future stewards?

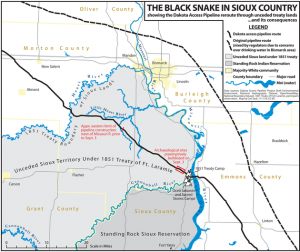

I believe that the future stewards of the James River will be those members of the community who simply care enough about their local environment to take a stand and fight. These members of the community can individually become environmental leaders even if they do not have all three characteristics. If they care about protecting their local environment, then they already have the required passion. Once they care, they will educate themselves on the relevant issues and gain the necessary knowledge. The third component, power, comes through collective action when multiple members of the community join forces and through the power of numbers motivate the government to support their cause. This is how community members, such as Susan from Michael’s post, can become leaders for environmental protection. Susan, who benefits greatly from the the natural environment around Reedy Creek, did not like the idea of the proposed stream restoration that is planned for a stretch of the creek. Her passion for the creek and its protection led her to better understand why the stream restoration could do more harm than good. Finally, her desire to protect the creek, combined with the will of her neighbors,

Save Reedy Creek Lawn Sign

has finally been heard by the city, evident in the fact that almost all of Richmond’s mayoral candidates oppose the stream restoration. Susan herself does not quite meet the criteria for environmental leadership, but I believe that the definition for an environmental leader needs to be expanded to allow for joint community leadership. Together, as a community, those who have filled there lawns with save Reedy Creek lawn signs act as environmental leaders. In Parr’s observation log about the Richmond Folk Festival, he writes a little about how community support for environmental protection is so important. This community support becomes even more powerful when members of the community come together to become environmental leaders.

Allowing for communities as a whole to be environmental leaders also removes some pressure for the individual, which is great for individuals like myself who carry the passion, and even some of the knowledge necessary for leadership, but who do not carry the required power for change. However, along with other individuals, such as my classmates, I can begin to influence greater environmental stewardship. For example, by myself I have the passion, and even some of the knowledge necessary to lead restorative change in the Gambles Mill Corridor. However, I have none of the power necessary to motivate the University of Richmond to make the changes I feel would best support the environmental protection of the corridor and the Little Westham Creek which runs through the corridor. But joined together with my classmates and others who support environmental interests on campus, we contain the power to influence the university to allocate more resources towards environmental protection, thus fully meeting the requirements for environmental leadership. Individual leaders are of course still valuable to environmental causes, but they are not the only way in which leadership can manifest itself and protect the environment for a cleaner and brighter future.