“WATER IS LIFE! WATER IS LIFE! WATER IS LIFE!”

As the protesters passionately chanted to the beat of a drum and shouted outside of the Army Corp of Engineer’s office in Richmond, I stood amidst the crowd, chanting along, but also observed the people around me. I saw colorful posters saying “No one holds the right to destroy” and “I stand with Standing Rock”. The $3.7 billion dollar Dakota Access Pipeline project would carry oil from western North Dakota to Illinois, where it would be linked with other pipelines. However, the pipeline crosses ancestral lands that the members of the Standing Rock Sioux tribe hold dear, and it would also be a massive environmental and health concern if the pipeline would break near the Missouri River, which is the tribe’s main water supply. People around me talked about the hours spent making posters the night before and arranged rides for people who did not have ways of transportation. People who came from North Dakota gave testimonials about residents getting charged for trespassing and rioting when they were actually participating in peaceful protest, the horrible conditions of the prison cells, and police officers turning in their badges after witnessing the violence ensued at Standing Rock. As I stood there, holding the colorful spray painted sign, I began to feel a sense of community with not only the people around me, but the rest of the world as we stood together in solidarity.

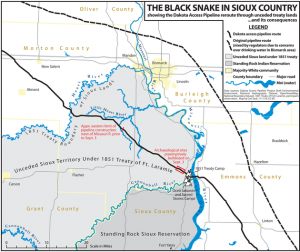

Map accurately depicting the controversy of the North Dakota Access Pipeline

Given that this was my first protest, this experience touched me and fascinated me on how people from various backgrounds came together for a united cause. A similar event happened in the Richmond community with the Reedy Creek Restoration project. The project was supposed to reduce excess nutrients by cutting down multiple trees to meet federal clean up rules, or as Parr stated, “nothing more than a government project to just “check off the box” and say they did something beneficial, without actually looking up the details.” There was no real evidence that suggested benefits from cleaning up the creek. People who were passionate about the issue went to the city council meetings and posted signs outside of their house saying “Reedy Creek Stream “Restoration”” with a bold red sign over it. The Richmond City Council ultimately voted 8-1 against in state grant funding for the project, bowing to strong opposition from South Richmond residents who opposed the water-quality measure because it would mean the removal of several hundred trees.

Given the previous two examples, nature and our surroundings can influence and inspire people as a group to act. As Jack mentioned in his previous blog post about the Richmond Folk Festival, he illustrated the importance of group mentality and the community effort in the accomplishment of any social cause. There are obvious benefits that a group can accomplish, but where is the evidence of the benefits being exposed to nature to the individual? The article from National Geographic explains the specific benefits to the brain when exposed to nature. Nature allows the prefrontal cortex, the brain’s command center, to dial down and rest compared to volunteers sitting in a parking lot or sitting in a lab. They also found that when volunteers looked at urban scenes, brains showed an increased blood flow to the amygdala, which influences fear and anxiety. However, when even viewing just pictures of nature, increased blood flow to the anterior cingulate is observed, which is associated with empathy and altruism. Perhaps nature makes us nicer and calmer (maybe that’s why Earth Lodge gets along so well compared to other SSIRs, who knows). According to research from the University of Exeter Medical School, they found people who lived near green spaces reported less mental distress, even after adjusting for income, education, and employment.

Places across the country and around the world are starting to realize these benefits of nature. South Korea embraced this medicalization of nature as many suffer from work stress, digital addiction, and intense academic pressures. Korea has healing forests, where people go to escape into nature for days, weeks, and sometimes months at a time. Korea even offers a forest healing degree program at Chungbuk University, which practices prenatal forest meditation, wood crafts for cancer patients, forest burials, and so much more. Due to increased knowledge of these health benefits, visitors to Korea’s forests increased from 9.4 million in 2010 to 12.8 million in 2013. There are also famous areas in urban areas such as Central Park. The designer of Central Park, Frederick Law Olmsted, said, “If we analyze the operations of scenes of beauty upon the mind, and consider the intimate relation of the mind upon the nervous system and the whole physical economy, the action and reaction which constantly occur between bodily and mental conditions, the reinvigoration which results from such scenes is readily comprehended. . . . The enjoyment of scenery employs the mind without fatigue and yet exercises it; tranquilizes it and yet enlivens it; and thus, through the influence of the mind over the body gives the effect of refreshing rest and reinvigoration to the whole system”

So, how does this relate to us in our own lives? In class, we have explored how the James river, or any river, brings people together and forms a community, but we have not investigated the intrinsic benefits of the individual. As Natalie stated in her blog, “parks and green spaces allow for enjoyment of nature and wild, natural, growing things; they provide cleaner air, a dynamic of peace and quiet, and the chance to not be surrounded by so many other humans or so much chaos and noise.” With the knowledge that nature has health benefits to the individual, the knowledge can incentivize not just us, but also the public to go outside and take in nature as well. I’ll leave this with the question that Michael had earlier in class in relation to this topic: how do we make people passionate about the outside world, especially when it brings so many benefits to us as individuals and the community as a whole?