My dog’s tail wags furiously as she playfully prances back and forth in the gravel parking lot. It is a struggle to clip her leash on before she gallops over the small grass median and onto the Norwalk River Valley Trail. Nearly four hundred miles away, local Richmond citizens walk out their backdoors, dogs in toe, planning on strolling the Gambles Mill Corridor. What role do urban and suburban trails play in the communities they connect? Are they wasted spaces that could be used for more efficient and practical purposes? These questions are vital as my hometown, Wilton, CT, continues to lengthen the Norwalk River Valley Trail and the University of Richmond continues to plan the Gambles Mill Corridor.

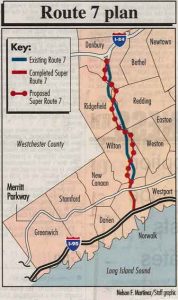

This map shows the current and projected sections of the NRVT that will span the entire Norwalk River watershed, connecting five different towns.

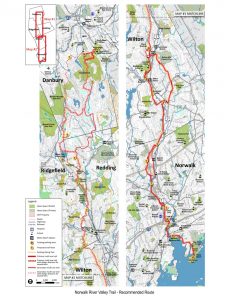

The Norwalk River Valley Trail (NRVT) is a projected 38-mile path within the Norwalk River watershed. The recreation and commuter corridor is projected to connect five different townships, providing connectivity for walkers, runners, hikers, cyclists, students, employees, pets and, on some sections, horseback riders. The Wilton loop has significantly progressed since the town began to connect previously existing public trails during my senior year of high school.

The longest section of the Wilton corridor is built on land owned by the town previously set aside for the rerouting of the Super 7 Highway. In 1957, the Connecticut Highway Department proposed to widen the current US 7 highway from two lanes to four, but after spending nearly 33 million dollars on acquiring the necessary land to build the new highway, the Department’s proposal was delayed by local towns rejecting the plans. It was not until 1974 when the Department pressed for another US 7 extension, this time planning to pave 469 acres of woodlands and 157 acres of wetlands, including state park properties. In the coming decades, 330 families and 19 businesses would be removed as the highway’s final details were falling into place. Boundary disputes between public and private land extrapolated into large political debates as homeowners challenged highway planners. Residents were concerned about how adjacent land use would affect their personal properties and the uninhabited forests between private plots. According to Hansen and DeFries, any industrial construction could decrease the size of ecosystems, disrupt the natural cycles within the area, wipe out a vital resource or cause edge effects that negatively impact surrounding wilderness. Additionally, all the new pavement would be impervious and prevent rainfall from percolating into the soil while simultaneously wiping out flora biodiversity and destroying habit corridors for fauna.

Wilton’s sense of region and space increased dramatically as it was preparing to shift from a small, rural community to a series of exits on a high-speed freeway. Most residents found themselves frustrated with how the human dimensions of their environment would soon outweigh the natural elements surrounding their homes. In short, many found what Monica defines as the local land ethic to be unbalanced. Interstate connectivity would improve, but it would so at the cost of precious wetlands and a proud psycho-geographic sense of bucolic community.

Opponents to Super 7, including the Tri-State Transportation Campaign, Friends of the Earth, the Housatonic Valley Council of Elected Officials and a coalition of local residents, eventually dismantled the major plans in the 1990’s. During my years as a Wilton resident, sections of US 7 would be marginally widened; however, the highway would not be rerouted through forestlands or wetlands. As plans for the highway were being refuted and designs for a green corridor were being suggested, Pat Sesto emerged as an environmental leader for Wilton. As the director of Environmental Affairs for the town since 1992 and chair of the NRVT since its early stages, Sesto was a driving force behind much of the trail’s organization and design. Although she claims that it is “not Pat Sesto’s trail, [it] is Wilton’s trail,” Sesto was a consistent figure head, repetitively advocating for the corridor and its importance. Holding political power made it easy for Sesto to take action, but her passion for the environment and the trail itself was the key to her success. By communicating and negotiating with both local residents and those of higher political standing, Sesto effectively made the NVRT a focus for the town. As Dennison and Thomas state, “knowledge, power, and passion together are a potent combination” and Sesto had all three.

Signage along the trail urges residents to “finish [funding] this project together, as a community.”

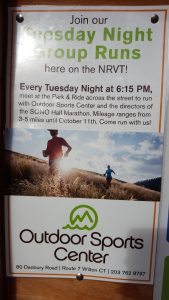

Today, the NRVT remains partially completed, serving as a fragmented wilderness corridor for recreation and commuting alike. The middle school and high school cross country and track & field teams use the trails as well as individual runners and cyclists. Young and old families are often seen casually walking dogs or riding bikes along the gravel path. Local businesses even host weekly group runs and 5k races where customers can buy merchandise, illustrating just one aspect of the NRVT’s economic benefits for the town. In this way, the trail serves as a focal point of Wilton, connecting community members of different backgrounds as well as a variety of local businesses.

Physically, the trail spans five townships, joining the entire Norwalk River watershed together. This provides a safe means for residents to access main streets, train stations, schools, offices and bus stops here in Wilton, but also in Danbury, Redding, Ridgefield and Norwalk. Because the trail spreads across these town boundaries, a large-scale sense of regional community is delicately crafted.

The trail allows users to safely cross major roads, increasing connectivity between residential areas and commercial areas.

Each of the five corridors depends on the other four in order to fully realize the grand concept of the NRVT. Because of this mutual reliance, each town is pressured into planning, funding and developing their respective section of the trail in a timely manner as to follow through with their promise of the trail.

Named for and located within a watershed, the NRVT helps to remind residents of their role within the global water cycle. Using the corridor gives participants a meaningful connection to the watershed, making the ownership and stewardship of the land all participants’ responsibility.

With the Norwalk River and its tributaries so close, trail users can actively witness how their lives are just small functions within a set of hierarchical ecosystems and cycles that power Earth and its many dimensions. Schnoor argues that understanding the movement of water is crucial for protecting water sustainability and the NRVT brings people closer to the River where they can witness the water cycle in action. Additionally, trash cleanups and other organized service projects along the corridor promote this idea of mutual accountability and help to educate the public on the movement of water.

The NRVT stands as a proud centerpiece of Wilton, CT. It serves as a recreational trail, uniting the town, as well as a commuting pathway. A sense of community functions at both the larger watershed scale in addition to a more localized town scale. The corridor draws residents to native businesses and promotes an active lifestyle for young and old residents alike. The history of our previously planned Super 7 Highway turned wilderness trail is truly a success story and illustrates the power of strong environmental leadership as well as the importance of community in prompting change. In these ways, the NRVT defines Wilton as a place in the minds of residents as well as on the map. However, the initial question still stands: where do community trails, such as the NRVT and Gambles Mill, lead? Perhaps it’s to main street, Long Island Sound or the James River. Maybe they lead to a more unified community or a more enriching lifestyle grounded in experiencing wilderness. For me and my dog, they just lead around the next bend, pointing towards a future of responsible environmental stewardship and united connectivity.