Category Archives: Things to Think About

3/19 – Class 8 Blog Post

Greetings class, I pray all is well and that you are enjoying the wonderful weather we’ve had lately! In Monday’s class, we discussed an array of topics, but for our discussion I want us to reflect more on books as … Continue reading

(2/24) Instruction and Assessment

Hi everyone! I hope everyone enjoyed the sun today – I can’t believe there was snow on the ground only a week ago! This week we discussed instruction and assessment. I really enjoyed exploring how to select and analyze assessments, … Continue reading

2/17 Blog Post: Blood On The River

Hi everyone! I hope you have had a great couple of days since class, and hope you all enjoy this snowy day! As we have been learning about Jamestown and Virginia’s history, as well as teaching these subjects, we read … Continue reading

“Blood on the River” Discussion

Hello everyone! I hope you are enjoying the snow day! This past week, we read and discussed Blood on the River by Elisa Carbone. We used an anticipation guide while we read and looked at how we could use primary … Continue reading

Reciprocal Teaching and Four Reads Strategy When Reading in the Classroom

Hi everyone! I hope everyone is enjoying the snow and day off this week! This week in class, we discussed and practiced the methods of reciprocal teaching and the four reads strategy, which both focus on helping students process and … Continue reading

Deep Learning Tools in the Classroom

Hello everyone! I hope you’re all enjoying your week and the beautiful weather we’ve had the past few days! For my blog post today, I’ve been thinking about some of the content from Chapter 3 of Visible Learning for Social … Continue reading

Teaching Hard History

Hi everyone! Today’s class session has definitely got me thinking more about how to go about teaching hard history in my own future classroom. Honestly, teaching history has been the topic I am most worried about teaching my future students, … Continue reading

Teaching and Tackling Hard History

Hello everyone! After this class, I definitely feel more prepared to take on hard history! However, there are still a lot of things to think about before creating those interesting lesson plans. My blog post will not be filled with … Continue reading

Detailed Lesson Planning: Effective or not? Should teachers be required to turn their plans in for approval?

Hello Class! This week’s class session was both informative and interesting. I’m not sure about all of you, but I thought watching a teacher conduct a lesson was extremely helpful as it provided me with various ideas and strategies. Adapting … Continue reading

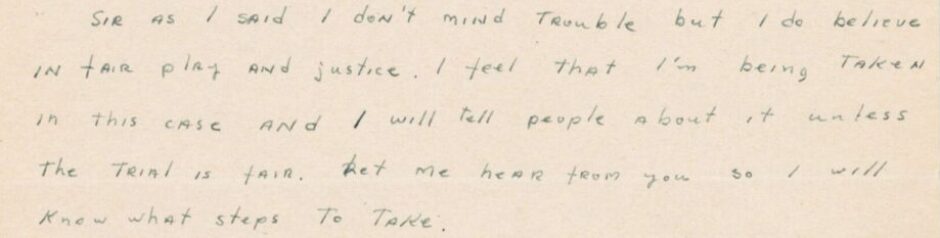

Primary Sources: Privacy and Integrity

Salut mes amis, Last class was enlightening for me in more ways than one. I had no idea that Richmond had a rare book/archives collection (an extensive one at that!) It was incredible to take a peek into the lives … Continue reading