From the outside, a paper publication appears to be the natural culmination of a linear research process in a particular field. In reality, it’s anything but—behind the scenes, the entire process is often a chaotic story, full of rinsing and repeating hypotheses, data collection, and ultimately, paper revisions. Few roads of research ever lead to a shiny new paper at all—most are scrapped somewhere along the way.

In theory, science is about asking questions and testing them with data. In practice, however, it’s also about surviving a publishing process that can feel like an extreme sport.

This huge challenge is well illustrated by the ongoing hunt for an HIV cure, as shown in the Nature editorial titled “Efficient mRNA delivery to resting T cells to reverse HIV latency.” It raises a question that many outside of academia may not consider: What does it take to publish a paper?

What’s the process of research reaching publication?

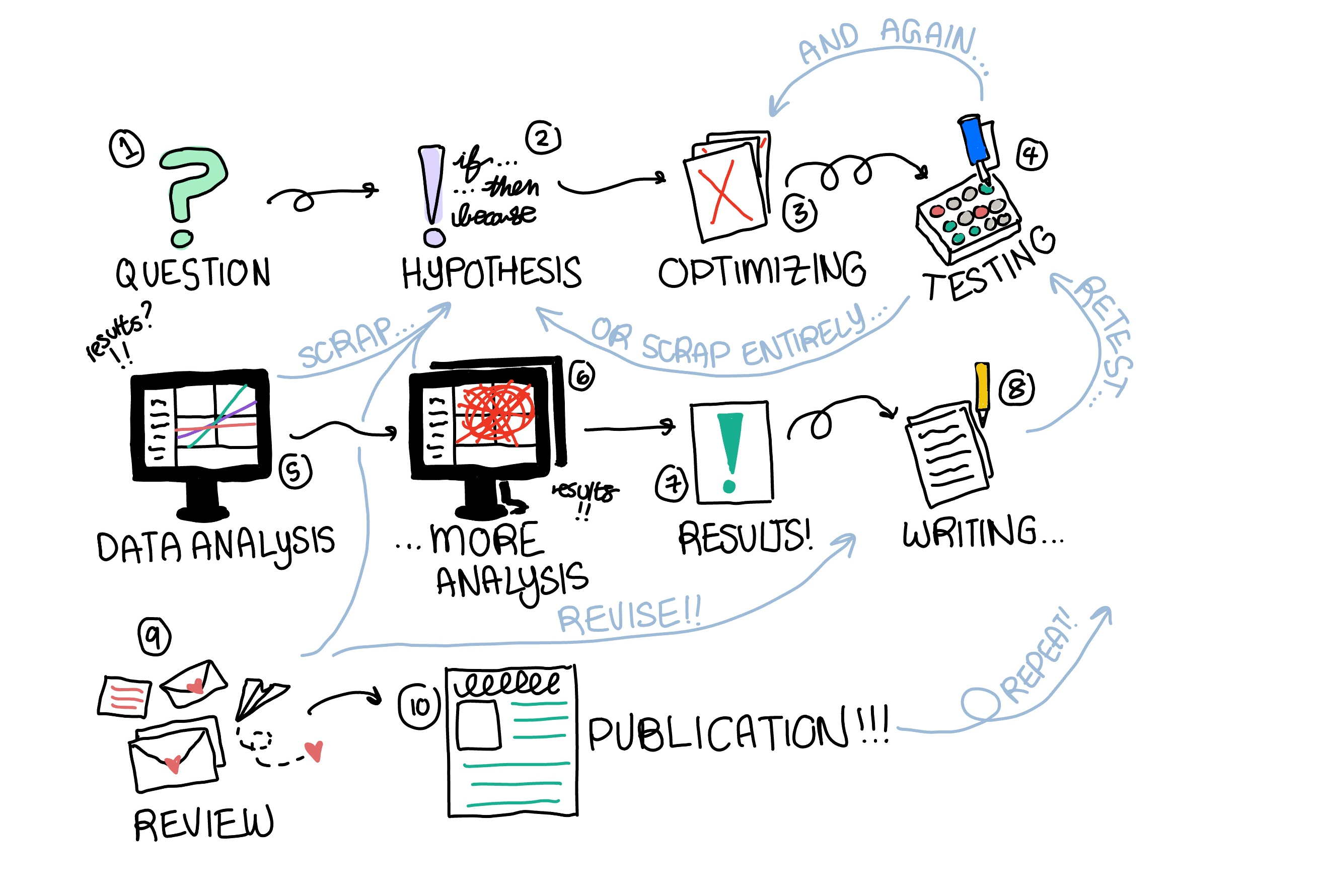

As any good sixth-grade science class has taught you, your research always begins with a question. Next, you form a testable hypothesis, planting the seeds for countless hours of work ahead. It might seem like all that’s left is to set up a straightforward experiment and start collecting data. But things are rarely that simple. Before meaningful data can be gathered, protocols need to be carefully designed and optimized, often through trial and error. It can take several “generations” of researchers before the assays run smoothly enough to reliably produce useful data, which is a long, patient process that rarely gets the spotlight. Congratulations! You now have a system that works, and you can start testing your hypothesis. But now begins the real challenge: data collection. The first time running an experiment can be nerve-wracking. Many projects hit roadblocks or even dead ends because the data doesn’t support the original idea. Even if the initial results appear promising, they must be repeated and verified multiple times to confirm their validity. Only after this painstaking process of validation can a research team begin to think about writing up their findings for publication. Now comes the publication process, which is a whole other challenge. First, you write the manuscript: a detailed story of your research. Here begins the peer review stage, where other experts review the paper and give feedback, ranging from asking for improvements to outright rejecting the paper. All of this, hopefully, will result in a paper that is accepted and published, with scientific credibility. Only then can you celebrate, as your research is officially part of the scientific record, ready to be read, tested, and built upon by others.

What’s this got to do with HIV research?

HIV research is a powerful example of how long and demanding the scientific process can be. Since 1985, over 44,000 papers related to HIV have been published on PubMed, which is just a portion of the global effort to understand and treat the virus. After HIV was first identified in 1981, the scientific community mobilized quickly. Even still, it took 7 years of drug development and testing to ultimately approve AZT, the first drug for HIV, and yet the virus soon developed resistance. Over the next two decades, researchers developed new classes of antiretrovirals, resulting in a breakthrough moment in 2012 with the approval of PrEP, a daily pill that drastically reduces the risk of transmission. Even this milestone was the result of years of foundational work and clinical trials. Yet the process hasn’t stopped there. A recent breakthrough in the search for the cure for HIV comes in the form of bringing HIV out of hiding in human cells, which has been the main challenge of finding a cure for HIV. This study reflects the years of work put into the paper before publication, and also the years of work following it to ultimately find a “cure”. HIV research shows that meaningful scientific progress is rarely fast.

Why does any of this matter?

The story of HIV research isn’t just about one virus, but rather it’s really about how science works. It shows the persistence required to turn questions into discoveries, and the many people, from scientists who are experts in their fields, to people like me, who are student researchers, that make all of this work possible. We often crave quick answers, but it’s important to remember that real breakthroughs aren’t instantaneous, like the accidental stories we hear about. Whether it’s pandemics, cancer, or even issues like climate change, science is a messy and rigorous process that is ultimately needed to drive progress forward.

Publishing a research paper isn’t just a singular moment of discovery, nor is it the obvious linear process that many believe it to be. Years of effort, trial, refinement, and even giving up, through multiple generations of scientists, have ultimately given delayed progress. HIV’s pathway makes that clear through its decades of research that developed AZT, PrEP, and the current discoveries made. Even after publication, the story doesn’t end. It simply enters the next chapter, and that’s really what the finish line in science is: just another step forward.

Recent Comments