Here is a story:

Many years ago, there was a trapper. He was interested in trapping a beaver so that he could sell its pelt, so he purchased a beaver trap. He set off into the woods with the trap, found a likely spot by a riverbank, and began to set the trap. Unknown to him, though, a clever beaver was nearby and observed what he was doing. The beaver, noting that the trapper was at work in close proximity to a nearby tree, quickly used his teeth to cut down that tree, which then fell directly onto the man, effectively (and ironically) trapping the trapper.

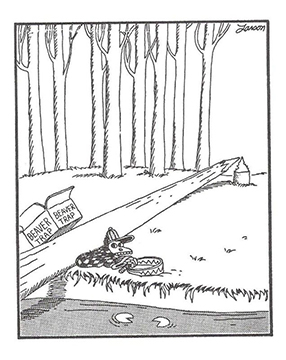

Here is the same story:

The Far Side © Gary Larson

You may have laughed at the second version; I doubt you did at the first. In order for this story to function as intended—to evoke an immediate response—the narrative must be delivered instantaneously and the tone must be unmistakable. In this case, a drawing can accomplish this where words do not.

Through much of our history, the written has enjoyed primacy over the visual—and for compelling reasons. There is a specificity and precision to words that images cannot match. However, with the ubiquity of the internet—which is after all essentially an enormous system of words and pictures—I think we are beginning to realize that pictures (and in the case of comics, my field of study: words combined with pictures) can be powerful communicators of certain types of information.

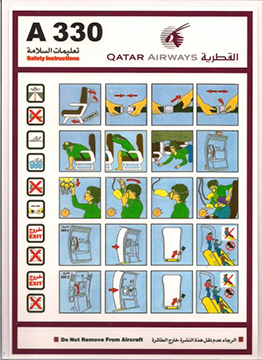

This certainly isn’t wholly new. When important information needs to be communicated directly, clearly, and immediately, often pictures (or sequences of pictures) are employed.

In the classroom, the word/picture combination we’re most likely to encounter is, of course, comics. Children’s and “all ages” comics have experienced a tremendous boom in the last decade or so and I’d be surprised if many K-12 teachers aren’t at least passingly familiar with books like Smile, Bone, Awkward, and Babymouse.

Past generations have seen comics as a “lower” form of reading than pure prose and have often sought to excise it from the classroom. In today’s classroom, though, I encourage teachers to embrace comics and recognize that it’s simply a different mode of reading—a mode with its own complex grammar, a type of literature that imparts information in a way that’s simply different than pure prose.

Can comics serve as a “gateway” for reluctant readers to eventually embrace prose reading? Sure. But a gateway is something we move through and then leave behind. In my experience, students who embrace comics initially continue to read comics as they add prose reading to their palette. Why should we view the two as mutually exclusive—one a stepping stone and the other our end goal?

And of course, there’s also a world of amazing classroom activities centered on making comics. Children love to draw. Comics have the ability to harness that love of drawing. Consider activities like making a comics autobiography or short memoir story, researching and drawing a comic book biography of a favorite historical figure, or make a comics adaptation of a chapter of a favorite prose book.

The children currently populating our classrooms have grown up in a ubiquity of word/picture combinations. Let’s embrace this and put it to good use by using comics—both reading comics and creating comics—in our classrooms.

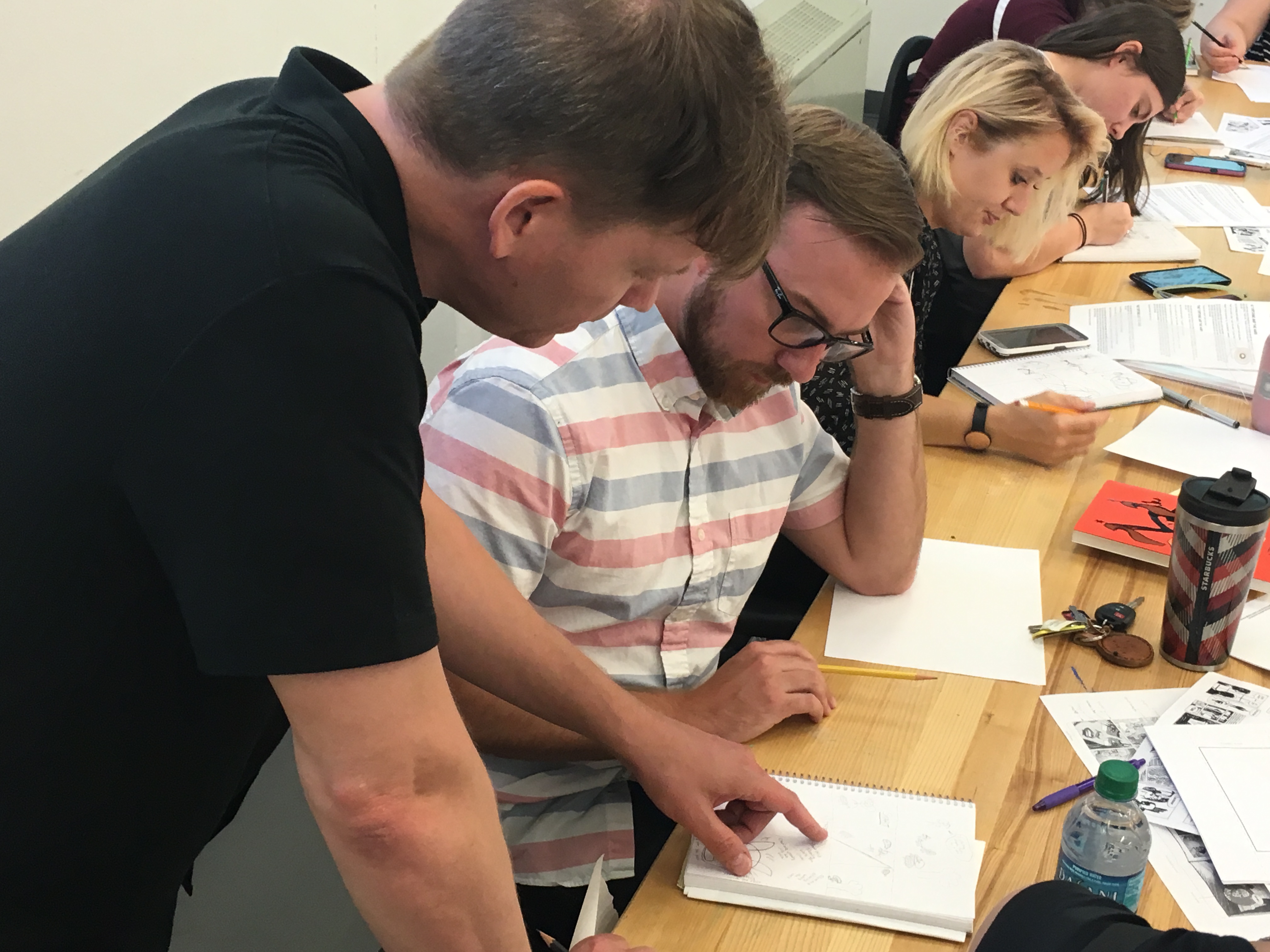

Ben Towle leading a teacher comic workshop at the Joan Oates Institute in 2016

This guest post was written by teaching artist Ben Towle, a four-time Eisner-nominated cartoonist. Ben has taught educators at the Partners in the Arts Joan Oates Institute. View his work on Instagram.