Scapino, the Trickster was performed from September 29th to October 1st with audiences of less than 150 people a night. The University of Richmond’s Department of Theatre and Dance adapted this 17th century Moliere piece with the help of Matt DiCinto. Director Walter Shcoen envisioned the show as a combination of comedic, classical theatre and modern fourth wall breaking held under the University’s starry sky at the Jenkin’s Amphitheater. The show was the first performance that the department had put on live since Covid-19 struck campus, which audiences applauded it for being such a strong comeback.

The play follows the story of a mischievous servant named Scapino who utilizes his trickery to bring two sets of lovers together and weasel around their fathers for a small fee. Scapino acts as a medium between the lovers and fathers, mixing up and passing along information and creating more chaos and comedy because of it. Professor Schoen opens the show with a small speech, ending it with a remark to Cameron to “set the mask.” Cameron rushes onstage and decides to wear the mask instead of placing it in its proper place, transforming him into one of the two zanni. His transformation is greeted with lighting effects, music, and the set coming together as a way to welcome the audience into the world of the performance.

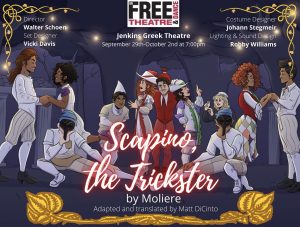

The audience quickly discovers that the play focuses heavily on identity, with distinct archetypes for two fathers and each of their servants, sons and daughters. Scapino, Leander, and Hyacinth all belong under the house of Signore Geronte, while Silvestro, Octavius, and Zerbinetta all belong under the house of Signore Argante. All of these different characters mostly wear different masks and costumes that reflect their identity. The fathers have masks with crooked noses, sharp features, and wrinkles, showcasing their age as well as their stingy ways. In contrast, the servants’ masks have more round noses with dimples and bruises to communicate their silly nature. Scapino was portrayed as wearing a pointy hat, dressed in all red, and a vest with a giant stomach. Underneath Scapino’s vest is a cushion, giving the illusion that the actor has an unrealistically large beer gut. This costume choice plays into the idea of servants having round features, while also being absurdly funny to look at. By the end of the play, all the secrets Scapino has kept are revealed and he even opens his vest for the audience and cast to see the cushion so they know that literally everything about him is a lie.

When watching Scapino move around the stage, audience tend to remark on his physicality as well as the fathers. Scapino hunches over with his arms out ape-like, his hunch represents the weight a servant must carry from labor and his arms and feet are ready to receive information or items. His bent appearance also makes Scapino’s jumps or when he stands up straight to be quite an amusing contrast to the hunch. The fathers, however, use canes and hunch over from old age or use the canes to stand up in a pompous manner. Signore Argante is more conniving and sniveling as he leans over and sticks his nose out in front of him. Signore Geronte is very upright, puffing up chest and sticking out his belly, resembling a very dumb and fat peacock as he struts with his large feather hat.

Another way that identity is explored in Scapino, the Trickster is the difference in hair color. The house of Signore Argante had family members wearing red wigs, while the house Signore Geronte had brunette wigs. These differences in hair color, as well as style, helped clue audiences into the age, gender, and family a character was. The fathers, for example, had long wigs, while the sons had shorter hair. The two daughters had matching hair styles, but different color wigs. The servants had no hair visible under their large pointy hats.With many intricate details present in the production, there is plenty of things to notice about how identity is communicated to the audience, leaving attendees wanting to return to discover them all and get a good laugh.