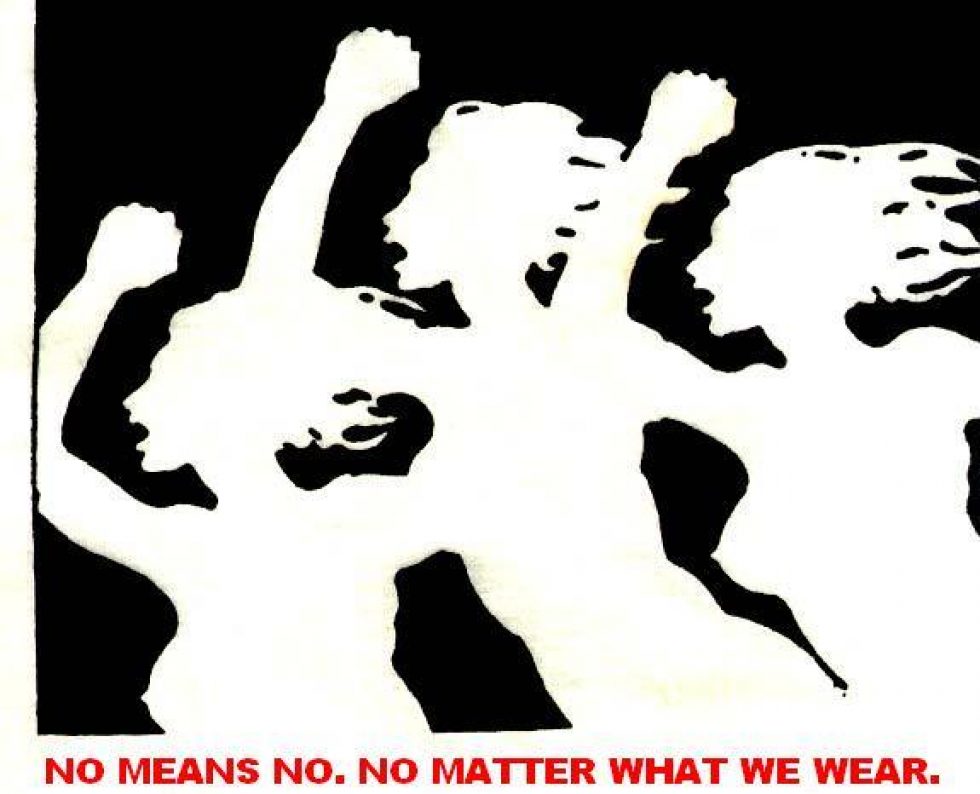

“Intersectionality Undone” by Sirma Bilge discusses how intersectionality has been depoliticized, which Bilge says strips it of its potential to create “social-justice oriented change” (405). She utilizes the examples of the Occupy movement and the SlutWalk movement to depict not only how important intersectionality is, but also how easy it is to overlook it, even within progressive movements. During the SlutWalk movement, which protested against blaming women and how they dress for their sexual assault, many Black women felt they did not have the “privilege or the space to call [themselves] ‘slut’” without validating the recurring stereotypes that they were inherently promiscuous or hypersexual, which people within the movement did not take into consideration, nor did they do anything about changing the name (406). Bilge uses this example to show how many movements will preach inclusivity and diversity, when in reality they often exclude or even misrepresent groups outside of their own.

Bilge also discusses neoliberal culture, and how it undermines and dilutes the founding concepts of intersectionality. The main example she uses is the myth of “posts,” like postracialism or postfeminism, and how they create a contradictory environment in which there are ideals of equality, but there is also a refusal to acknowledge race, class, gender, sexuality, ability, and citizenship-status, and how all of those factors exist and affect people’s lives. With the myth of “posts” also comes the idea that equality has been achieved, so there is no need for further action/forces, which Bilge mentions when discussing how intersectionality has been “hailed” and “failed”–meaning that some elements are intersectionality are considered, but are then overlooked or put to the side, which people accept because they think solely acknowledging intersectionality is enough.

She also mentions how neoliberalism has caused intersectionality to be “commodified and colonized,” meaning that everything is centered around diversity, but for the purpose of benefiting large corporations, in which diversity becomes “a sought-after signifier of sound judgement and professionalism” (407-408). She says that one of the main aspects of neoliberalism that maintains it is the constant projection of “human precarity and risk as entrepreneurial/developmental/funding opportunity,” which she also describes as ornamental intersectionality–basically the opportunistic use of intersectionality (408).

When looking at the whitening of intersectionality, Bilge does not look at Whiteness as a skin color, but rather as a structurally advantaged position. Therefore, the whitening of intersectionality has to do with decentring the role of race in intersectionality, which disciplinary feminists do a lot of. Bilge discusses disciplinary feminism, which is different from academic feminism in that its participants are usually more concerned about the institutional success of the knowledge they produce, rather than the institutional and social change that can come from that same production of knowledge. A common example of this is devaluing theory when it comes from feminists of color, which stems from the belief that their experiences do not equate to or generate theory.

The two strategies that whiten intersectionality that Bilge looks at are framing intersectionality as the brainchild of feminism and broadening the genealogy of intersectionality. Looking at intersectionality as the brainchild of feminism reframes it as a property of feminism and women and gender studies, which erases “intersectionality’s intersectional origins” and therefore downplays race and the role it plays not only in intersectionality itself, but also in the creation of the framework. Many European feminists do the same thing and don’t even consider race as an analytic category itself, but rather look at ethnicity, religion, culture, etc. They also downplay the importance of Black feminism and intersectionality’s ties to it by saying that the emergence of intersectionality was “in the air,” rather than acknowledging the origins of it. Broadening the genealogy of intersectionality “[juggles] what is represented as recognition…while simultaneously pushing them into the background,” meaning that this was just another strategy to put White people at the forefront of intersectionality. Bilge goes on to say that White feminists should not be excluded from discussions of intersectionality, but bringing in White feminist scholars and saying they were an integral part of the origins of intersectionality “[obliterates] the fact that the political standpoint at the root of this theory and epistemology was constructed oppositionally to White feminism, not in tandem with it” (415).

In the conclusion, Bilge says that “those who argue that there is no need to argue about racial oppression because such oppression is never ‘purely’ racial are treating intersectionality in the abstract as a directive of universal application, for the specific purpose of suppressing discussion of racial oppression,” which I think sums up the significance of intersectionality, as well as how its absence and misrepresentations have very deep implications (419).

Questions:

- Like the Occupy movement and the SlutWalk movement, what are some examples you have seen of modern movements that also fail to acknowledge intersectionality?

- Where have you seen examples of ornamental intersectionality (opportunistic uses of intersectionality)?

- What are your opinions on “diversity culture”? Do you think its disingenuousness makes it inherently bad, or can the benefits outweigh the costs?

Well done, Sheila Mae. I hope in class we can apply this ti what is happening in our own back yard.